In the beginning there was no faculty.

For the first 54 years of its existence, the Collegiate School — later renamed Yale College — did not have a single professor. Between 1701 and 1755, a handful of young tutors assisted the lone rector of the fledgling school.

The University did not officially appoint its first professor until 1756, and the total size of the teaching force did not exceed six for another 50 years. Since that time, the professoriate has gradually expanded, reaching 37 professors by 1901 and 70 by 1953. As of October 2013, Yale has 445 tenured professors.

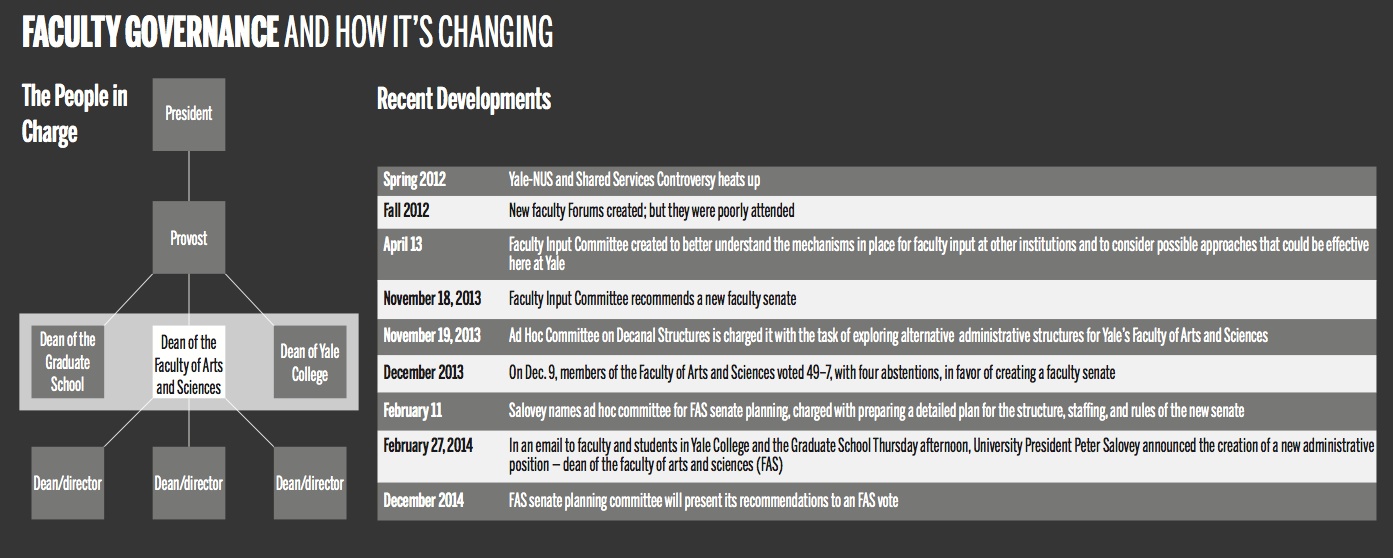

As the University grew in size and complexity, it also developed a hierarchical governance structure.

According to English professor Wai Chee Dimock GRD ’82, former University President Arthur Hadley was summarizing a long-standing practice when he said that “in the government of Yale College, the Faculty legislates, the President concurs, and the Corporation ratifies.”

But the past several decades have seen a widening rift between faculty and administrators, and recent conflicts over Yale-NUS, Shared Services, West Campus and budget cuts, coupled with a new administration, have brought issues of faculty governance to the forefront.

Within the next few years, two changes will alter the governance landscape of Yale: the addition of a new dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences and a new faculty senate.

Professors interviewed said these concepts are far from original, citing many other universities that have faculty deans and faculty senates.

“The idea is not new, although the possibility that the University might take the idea seriously is new,” said Jerome Pollitt ’57, a professor of classical archeology and the history of art.

Though over three dozen Yale professors and administrators interviewed were split on the success of current governance structures and the potential effectiveness of a new senate and deanship, most agreed on one central idea.

“Nothing can be more important to the intellectual vitality and well-being of Yale than faculty governance,” Dimock said.

A NEED FOR CHANGE

Many faculty members interviewed said it is no coincidence that the addition of a new faculty senate and a new dean of the FAS corresponded with the transition to the University’s 23rd president.

“These changes are happening because every generation brings its own ideas into play,” said history professor Carlos Eire GRD ’79.

University President Peter Salovey agreed, albeit in his own words. A presidential transition stimulates thinking about whether organizational structure of the institution should be examined, Salovey said.

Still, philosophy professor Michael Della Rocca said these changes are “long overdue.”

As the University has become increasingly complex, faculty members said Yale’s administrative structures and mechanisms for faculty input have proven insufficient.

Currently, the University holds monthly Yale College faculty meetings with agendas set by the administration, meetings of the FAS Joint Board of Permanent Officers and occasional town-hall-style meetings of the whole Faculty of Arts and Sciences.

These town hall meetings have seen few changes since 1940, despite the “complexity and coordination challenges” that have accompanied the 10-fold growth of the faculty, according to a report compiled by the Faculty Input Committee — an ad-hoc committee convened last spring to evaluate faculty governance at the University.

In recent years, history and law professor Daniel Kevles said the faculty has found that it does not have a “good vehicle for expressing its views” in opposition to University decisions such as switching to Shared Services — a centralized business service center for a number of administrative tasks like payroll, accounts payable and vendor compliance.

“The financial recession exposed the system of faculty governance as inadequate,” he said.

At the same time, the increasing complexity of the University has loaded additional responsibilities onto the shoulders of the University provost and Yale College dean positions.

“I think there’s a recognition that two of the current administrative positions at Yale are too overwhelming for any human being to undertake,” philosophy professor and Deputy Provost for humanities and initiatives Tamar Gendler said earlier this year. “And one of those positions will become more overwhelming with the addition of two new residential colleges.”

Salovey said changes in the faculty promotion system, and the Yale College dean’s responsibility over a variety of campus life issues, including Title IX and alcohol regulations, have greatly expanded the responsibilities of the Yale College dean.

Meanwhile, the number of faculty, courses offered, graduate students, research output and budget issues have grown over the past few decades, making the provost’s job more difficult, economics professor Giuseppe Moscarini said.

“I think the volume and entanglement [of these responsibilities] is untenable,” Provost Benjamin Polak said earlier this year. “I think there has to be some level of change.”

A TURNING POINT?

The lack of an adequate structure for faculty to influence University decision-making became clear in spring 2012, when some professors wanted to mobilize opposition to Yale-NUS — the liberal arts college Yale founded with the National University of Singapore.

Several professors expressed outrage that they had not been adequately consulted by the administration before Yale agreed to the joint venture.

“The Yale-NUS matter was a classic example of ignoring the faculty while making a major overseas commitment in the name of the University, then presenting the faculty with a ‘fait accompli’ and pretending to go through some consultative measures, such as a ‘town meeting,’” Assyriology professor Benjamin Foster GRD ’75 said.

In the midst of faculty dissent over Yale-NUS, professors began discussing ways to change the mechanisms for faculty input at Yale. In response, Salovey and Polak instituted experimental “FAS Forums” in fall 2012 with agendas chosen by a faculty vote. But these forums were poorly attended during the 2012–’13 academic year, and Salovey appointed a Committee on Faculty Input in April 2013 to examine the issue in more detail.

The proposal to create a faculty senate emerged from the Faculty Input Committee’s November report, which found that some professors feel Yale’s existing structures for faculty input do not provide appropriate opportunities for faculty to have their voices heard.

“Our research on other institutions revealed that Yale is a considerable outlier in terms of faculty governance,” the committee wrote in its report. “Outside of the research universities we examined, so far as we are aware, elected faculty senates or councils are near universal.”

The committee brought the issue to a vote on Dec. 9. With four abstentions, the FAS voted 49–7 in favor of creating the senate within the next few years.

In February, Salovey appointed a committee to discuss and make recommendations on the senate’s structure and procedures to the FAS no later than December 2014.

Shortly before Yale College Dean Mary Miller and Graduate School Dean Thomas Pollard announced in January that they would be stepping down at the end of this academic year, Salovey commissioned a Committee on Decanal Structures to examine Yale’s administrative infrastructure.

The committee’s report identified several major weaknesses in the current administrative structure, including a lack of dedication to long-term planning, a lack of clear lines of authority, limited opportunities for faculty involvement in leadership, limited independent voices for faculty and the unmanageable scope of the responsibilities allocated to the Yale College dean and University provost positions.

The FAS dean, who Salovey said will be named after Commencement, will take on some of the Yale College dean’s and the provost’s current responsibilities.

With both the senate and the new deanship, Yale is trying to make its governance more responsive to the increasing complexity and scale of the problems facing it and ensure that faculty has a greater voice, said philosophy professor Stephen Darwall ’68.

A LACK OF TRUST

Still, many faculty stressed that the addition of a new FAS dean and a faculty senate are not simply by-products of a new administration leading an increasingly large, complex University.

Rather, the changes need to be evaluated in the context of a growing tide of faculty unhappiness with the University administration over the past few decades.

Under former President Richard Levin, Yale adopted a more top-down, corporate leadership style, English professor Katie Trumpener said.

Foster said members of the administration have urged a market-driven approach, viewing research and teaching as products offered to consumers.

As a result of this mentality, many professors worry that faculty opinions no longer carry weight at Yale.

Art history professor Pollitt said the “executive types” tend to view the faculty as just one more troublesome component of “the staff.”

“As long as faculty members do not interfere with or impede the business end of the University, they are content to look on the faculty as a group of harmless eccentrics and have little interest in how they govern themselves,” he said.

Many professors agreed, arguing there is a perception among the faculty that the Yale administration has become too powerful and has developed misguided objectives.

While the addition of a faculty senate could help make Yale’s governance more democratic, Latin professor Christina Kraus said “multiplying deans” by adding a faculty deanship could pull Yale in a more autocratic direction.

English professor Leslie Brisman said he “cannot fathom” the reason for adding a FAS dean. The existing Yale College dean position cannot be too overwhelming, he said, adding that Miller completed two books while serving as dean.

“I think Yale has a good administration, which understands pretty well the views of faculty and students,” said English professor David Bromwich ’73 GRD ’77. “But the tendency of all bureaucracy is toward expansion: more monitoring, more evaluation, and a drift toward control and uniformity — a tendency that defeats the ends of a liberal education. You can’t guard too much against it.”

A LOOK BEYOND

Concerns about faculty governance are not unique to Yale, according to professors, faculty and experts interviewed from Harvard, Stanford, the University of California — Berkeley and the University of Chicago.

“I think most institutions have top-down governance, if you mean by that there is strong executive authority in American research institutions,” said Henry Rosovsky, Harvard economics professor and former dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Harvard. But he added, “I think that [with] anything that touches on the academic life of the institution, one needs to get input and opinion from the faculty.”

Shared faculty governance is one of the six characteristics necessary for high-quality universities, which also include academic freedom, merit-based admission, personal interaction, cultural identity and nonprofit status, Rosovsky said.

While faculty generally do not want to have input in every decision their employer makes, they often expect to be consulted on issues of strategic importance, said Joseph Zolner, senior director of the Harvard Institutes for Higher Education.

“With the decision Yale made to move to a faculty senate, Yale was the last Ivy to do that,” Zolner said. “In a sense, Yale is finally catching up to peer institutions in that regard.”

David Palumbo-Liu, the current chair of Stanford’s faculty senate and a professor of comparative literature, said governance at Stanford is more “lateral and cooperative” than top-down. The 55 elected representatives of the faculty senate represent a large part of the University, he said.

While each session of the Stanford senate has built-in time for the president and provost to make announcements and take questions, only senators can vote, Palumbo-Liu said. Even though the senate has no direct say in anything regarding the finances of the university, the senate must approve all educational and research policies, he added.

University of California, Berkeley’s Academic Senate, founded in 1920, is endowed with a considerable amount of power, professor and Chair of the senate Elizabeth Deakin said, adding that their system of shared governance is “really quite different from Yale.” The senate establishes the conditions of undergraduate admission, approves new courses and advises the administration on most matters.

Deakin added that the relationship between the UC Berkeley faculty and the administration is a partnership. Beyond the research and scholarship done by the faculty, they also bring in one-third of the money that supports the university, Deakin said.

“We’re not the hired help,” she said.

Nevertheless, professors at several of these institutions with faculty senates expressed criticisms.

While Stanford history professor Peter Stansky ’53 said the Stanford administration is fairly transparent, he lamented that there is an excess of administrative positions, which has led to a more corporate university.

Similarly, Robert Bird GRD ’98, a Slavic language professor at the University of Chicago, said governance has been a contentious issue at the school in recent years, especially in the face of what many faculty perceive to be the “imperial” presidency of Robert Zimmer, who oversaw the creation of a Confucius Institute — a language institute sponsored by the People’s Republic of China — without the approval of the faculty senate.

Defining the jurisdiction of faculty senates is always a messy business, said University of Chicago professor Clifford Ando.

“Major American universities have for a long time been drifting or, sometimes, rushing, to top-down management,” said classics professor Victor Bers. “Yale is now the most top-down of the standard comparison group. Still, I’m keeping my fingers crossed.”

NO EASY FIX

Almost 150 years ago, President Theodore Woolsey said in a speech that Yale’s faculty should take it upon themselves to change and improve the University.

“If there are defects in our system, the faculties are, as they ought to be, mainly responsible,” he said.

Still, it remains altogether uncertain how — or if — these changes will shift power dynamics at Yale, professors said.

History professor Beverly Gage ’94 said a faculty senate would create genuine democratic mechanisms in University governance. And because the new FAS dean will likely be a member of the faculty, Gage said she would not view the addition of another administrator as a move towards corporate governance.

But Brisman said the creation of a faculty senate is unlikely to change much, adding that the low attendance levels at current faculty meetings might indicate that few professors would be interested in the new senate.

“I do not have the impression that the majority of faculty at Yale are deeply concerned with this issue [of governance],” Foster said.

Foster said it also remains to be seen whether the body will have effective authority or end up just being a forum for discussion with a purely advisory capacity.

Though English professor Jill Campbell GRD ’88 said the new faculty senate may help faculty members make their voices heard, she said she worries that faculty members will still be shut out of the decision-making process as a result of their lack of access to information.

Political science and philosophy professor Seyla Benhabib GRD ’77 said the relationship of some programs, like the Jackson Institute and Yale-NUS, to the existing procedures of academic appointments and course review were never clarified to the faculty.

Campbell noted several instances in which faculty attempts to gain information and understand University-wide issues were met with resistance from the administration.

When Yale announced that the size of its faculty would not increase in the near future, despite the impending addition of two new residential colleges, for example, Campbell said she requested data on specific areas of faculty growth over the past 10 years. She was denied access to the information because it was “confidential,” she said.

“In the context of an administration so committed to non-transparency — and at times, active obfuscation — my own requests for information seem presumptuous,” Campbell said in an email. “Who am I, in particular, to ask for such information? No one or nothing, in particular — just a long-time member of the permanent officers of Yale who wants to know what every faculty member should be able to know, in order to formulate informed views of what the University needs for its long-term well-being and of the quite major decisions that are being made by the few in the know.”

Foster also said he does not see how “yet another dean” will improve Yale’s governance.

Still, most professors said they are willing to give these new structures a chance.

Kevles said the new faculty senate in particular is a step in the right direction.

“It might be inefficient, but democracy is inefficient,” he said.

Campbell said she is “hopeful and excited” about the prospect of a faculty senate and believes it has potential to serve as a forum for fuller faculty participation in University decision-making.

Faculty governance should be important to every faculty member at Yale, English professor David Kastan said. Decisions are made every day, and many of them should be made in close consultation with the faculty — and some are arguably matters for the faculty alone to decide, Kastan said.

“This place is filled with some of the most creative and smartest minds that one could find anywhere,” Salovey said. “Why wouldn’t one want to take advantage of that faculty?”