Looking around at the students hurrying up and down the bustling stage, Jonathan Lian ’15 already knew it was going to be a long night.

Lian — the president of the Yale Dramatic Association — was overseeing preparation for the Freshman Show, a yearly production that takes hundreds of hours to put together. But Lian is not a Theater Studies major — he studies Global Affairs — nor does he aspire to work in drama after graduation.

“I like doing this. I like the people,” Lian explained, adding that he tries to devote time to both academics and extracurriculars.

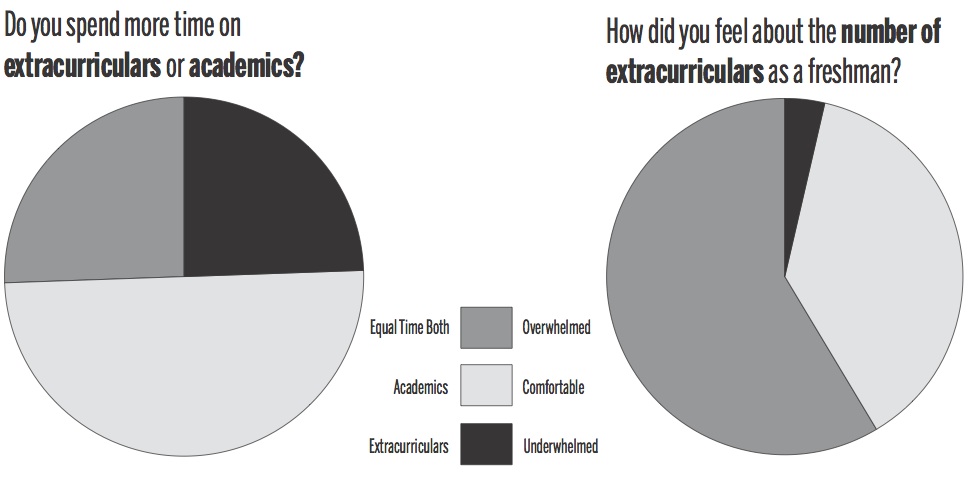

At Yale, activities outside the classroom make up a significant portion of campus life. In a News survey of 105 students, 27 said they spend an equal amount of time on academics and extracurriculars, while 26 others reported spending more time on extracurriculars. On average, 46 students said they spend more than seven hours a week on their main extracurricular commitment.

At Yale, activities outside the classroom make up a significant portion of campus life. In a News survey of 105 students, 27 said they spend an equal amount of time on academics and extracurriculars, while 26 others reported spending more time on extracurriculars. On average, 46 students said they spend more than seven hours a week on their main extracurricular commitment.

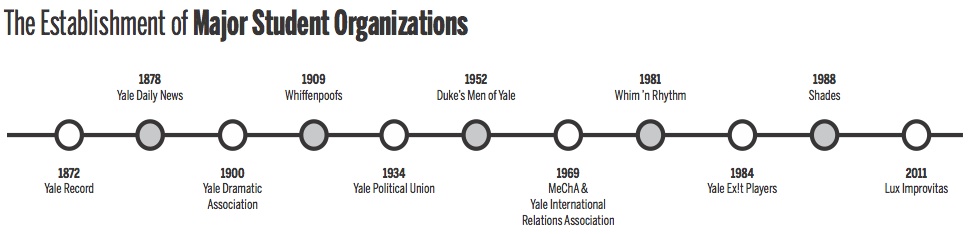

The number of student organizations registered with the Yale College Dean’s Office (YCDO) has skyrocketed over the last decade. As of last month, 385 student groups were registered and 100 additional groups were in the process of registration. The nearly 500 student organizations at Yale tower over Princeton’s 305 and Harvard’s 400, even though the latter has a larger undergraduate population. Cornell, Columbia and the University of Pennsylvania have more groups than Yale, but they also enroll many more students.

But the ever-increasing abundance of student groups also causes a number of logistical challenges — including the fact that there is simply not enough funding to amply support all of them.

In a November 2013 column in the News, Undergraduate Organizations Committee (UOC) Chair Benjamin Ackerman ’16 explained that the UOC received more than 500 grant applications in the fall semester, cumulatively requesting over $350,000. But the UOC — which receives funding from the President’s Office, YCDO and undergraduates’ Student Activities Fee (SAF) — is only able to dole out $205,000 for the entire year.

When asked whether the YCDO will one day have to cap the amount of organizations that exist on campus, Associate Dean for Student Organizations and Physical Resources John Meeske ’74 leaned forward in his chair and took a moment to think.

“It certainly could be possible,” he mused. “I’m very divided on that.”

BILLS, BILLS, BILLS

Since November, the UOC and its parent organization the Yale College Council (YCC) have collaborated in an attempt to more fairly distribute funds. The new YCC constitution, ratified in February, gives its members the opportunity to review UOC funding decisions and request changes after reevaluation and deliberation. The YCC also opened discussions about potentially altering the SAF.

When a student group needs funding, its treasurer must parse through UOC guidelines and submit a grant application that the UOC will then consider in a meeting. Each semester, existing groups are allowed to request up to $600 in administrative grants from the UOC and new organizations in their first semester are eligible to request up to $300.

Ackerman and the rest of the UOC have the difficult job of dividing up the UOC’s limited funds, and most student groups do not receive the total of what they request even if their applications fall completely within the guidelines.

“The guidelines need to be revamped,” Ackerman admitted. “We’re trying to be very careful and not hurt any students.

Insufficient UOC funding has hit groups hard across the board. In the News survey, 57 percent of students said they know of organizations that did not receive enough funding to cover expenses.

To increase transparency, Ackerman made all funding requests and decisions available for online viewing this semester. According to the site, even the requests that the UOC agrees to fulfill come with qualifications — and in the recent funding cycle that ended on March 7, only 26 of 62 groups were awarded their full requested amounts. Only five groups received the maximum of $600.

Student groups have dealt with the limited funding in a number of ways, including seeking funding from other campus offices. The Office of LGBTQ Resources awards a certain amount of funds to groups that relate to LGBTQ issues. Maria Trumpler, director of the office, acknowledged that her office has also been short on funds this year but added that she enjoys being able to support students’ efforts.

Still, she encouraged groups to ask themselves the question, “Can you scale back?”, when thinking about expenses and funding.

“People don’t have a sense … of what is necessary,” she said.

Some groups, such as publications, have taken it upon themselves to self-fund through soliciting advertisements.

Grant Fergusson ’16, business manager for the Duke’s Men a cappella group, said most a cappella groups stay self-sufficient from money made at off-campus performances, which fund their tours and CDs.

But not all groups can thrive without sufficient outside funding. Amy Napleton ’14 is the president and former co-director of Yale’s oldest improv comedy group, the Exit Players. She said her group recently suffered a noticeable decrease in UOC funds that cut down on the range of schools at which the group can perform.

“It is more meaningful for us to do shows at schools that can’t pay us anything,” she said. But without sufficient funds, the group cannot cover such tours.

The current Exit Players have fortunately been able to self-fund their travel so far, said co-director and business manager Will Adams ’15. But he went on to say that the group has become much more mindful of its expenses, and it has ramped up its number of local shows for the sake of revenue.

Napleton stressed that the group cannot always rely on its individual members being able to independently support travel, and that she hopes the Players will soon be financially stable enough to not require significant out-of-pocket contributions.

With groups like the Exit Players in mind, Ackerman has pledged to continue looking for ways to improve the funding system. One possibility has to do with the Student Activities Fee.

Since 2009, the SAF — which students can choose to opt out of — has remained at $75 per year. The money amassed by the fee is divided for use between student government bodies (50 percent), club sports (15 percent) and UOC funding for student groups (35 percent).

Over the past couple weeks, the YCC has discussed making changes to the SAF. At all Ivy Leagues except Harvard and Princeton, the SAF is both mandatory and higher than it is at Yale.

Students at Yale can opt out of the SAF through their online student accounts. But at Harvard, the opt-out process involves the submission of a physical letter to the administration, according to YCC President Danny Avraham ‘15.

Ackerman said he personally believes Yale’s SAF should be increased and is open to discussion on whether or not it should be mandatory. He is also willing to discuss having a larger portion of the SAF be allocated to funding for student groups, he said.

But finding sufficient funds is far from the only problem.

Under current policy, the screening process for the formation of new student groups is fairly lax. Though students and administrators praised this laissez-faire approach as conducive to creativity and freedom, many also raised concerns about the rise of illegitimate groups and groups too similar to already-existing organizations.

And even if the UOC were able to give out as much money as desired, groups would still compete for the most valuable resource of them all: student interest. Without adequate membership, any student organization — no matter how unique its ideas, or lofty its goals — will flounder.

DEFINING LEGITIMACY

At least once in their Yale careers, students wade through jostling crowds and colorful flyers in Payne Whitney Gym for the college-wide Extracurricular Bazaar.

The event, held during both Bulldog Days and Camp Yale, is a chance for the roughly 500 student groups on campus to attract new members. The bazaar is a flamboyant show of the diversity of student organizations on campus. Within the gym, students will find comedy groups, a cappella groups, other performance ensembles, publications of every genre, countless service groups, academic organizations and many more.

It is no wonder that 58 percent of respondents in the News’ survey said they were overwhelmed by the amount of extracurricular options upon first arriving to campus.

Yet most students interviewed said they appreciated the occupation of Payne Whitney’s every niche by student organizations — especially performance groups.

“They all do different things,” Napleton said about the four other improv groups on campus. “They’re all really funny.”

While the Exit Players specialize in short-form comedy, Yale’s newest improv group Lux Improvitas focuses on long-form improvised theatre, said Noam Shapiro, Lux’s director. Shapiro proposed that the diversity of comedic styles on campus also allows the different groups to learn from one another — so the comedy scene is more collaborative than competitive.

Fergusson put forth a similar sentiment about Yale’s singing community. Though the rush process for Singing Group Council a cappella groups is competitive, he said, he believes that those who do not end up in those groups can probably find another ensemble they will love.

But while Fergusson recognizes the complexity of the situation, he also believes there should be stricter regulations on groups forming.

![“[Yale is] over-saturated with groups. That’s just confusing for incoming students, especially in the music community.” -Grant Fergusson ’16, business manager for the Duke’s Men](https://yaledailynews.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/PhilippArndt_BDDBazaar-1-300x198.jpg)

“[Yale is] over-saturated with groups. That’s just confusing for incoming students, especially in the music community.”

-Grant Fergusson ’16, business manager for the Duke’s Men

Jack Newsham ’14, chairman of the historic humor magazine The Yale Record and a former deputy opinion editor for the News, took a stronger stance. While he conceded that his publication has learned from seeing what succeed and failed in newer publications and comedy groups, he also labeled other smaller publications “useless and opportunist.”

Newsham commended a handful of small publications that are able to finance themselves through advertisements. But there are other publications on campus that are “poorly designed” and “terribly written,” he said.

These registered student organizations not only use up limited funding but also crowd the physical space for publications as well, Newsham added.

“If I were someone who were interested in law or medicine, I wouldn’t want to read the Yale Undergraduate Journal of Law and Medicine,” he said.

Others pinpointed a concern over some student groups that are created to illegitimately “front” or “shadow” already-existing organizations, in a ploy to receive more money. Ackerman admitted that he is aware of the existence of such groups.

But Ackerman believes it is the responsibility of the YCDO — not the UOC — to determine a student organization’s legitimacy. Ackerman said he is not as concerned about overlapping organizations as he is about illegitimate groups continuing to apply for funds and then utilizing them in malicious ways that are inconsistent with their applications.

“Yale students are very smart and they’re very good at understanding the system and working within the system to get what they want,” Ackerman said. But Ackerman estimated that because of the UOC’s recent decision to more carefully scrutinize applications, less than 1 percent of funds this semester have been allocated to illegitimate groups.

The problem of overlapping organizations exists at other universities as well, though administrations view the issue differently. At Cornell, there are six club soccer teams, two different consulting teams and a plethora of performance groups. But multiple groups of the same kind are mostly embraced, said Cornell Assistant Dean of Students for Student Activities Joseph Scaffido.

Harvard Dean of Student Life Stephen Lassonde GRD ’94 said his office is increasingly focused on ensuring that student groups do not repeat so much. The reasoning behind this initiative has less to do with funding and more to do with student attitudes toward academics versus extracurriculars.

“Extracurriculars are becoming increasingly important in students’ lives … they say that they’re spending more time now on their extracurriculars than their academics,” Lassonde said. “We think priority should be given to their coursework.”

Meeske and Dean of Student Affairs Marichal Gentry voiced a different opinion.

Gentry said that while Yale is known for its great education, the University values holistic education and development of the whole person through “the creation of ideas and the ability to interact with other folks and cultures.” Gentry was quick to point out that academic organizations exist on campus as well.

Meeske also argued in favor of diversifying out-of-classroom experiences.

“The culture nowadays is that people don’t want to be pigeonholed,” Meeske explained. “In general, that’s great. We want to encourage people to do different things.”

“A SOCIETY OF FRIENDS”

A week ago, the YCC held an open forum — publicized in multiple emails to the student body — to hear student opinions on the student activities fee.

But aside from YCC members, only two students attended.

What does it mean that Yale students, the vast majority of whom are dedicated to extracurriculars, chose not to attend a meeting that could crucially change policy around student groups?

A day before the forum, students posted suggestions for improving current UOC funding policies on the Facebook group “Yale Ideas.” Ackerman said he was open to discussing the ideas posed on the page, including one suggesting that students should be able to choose how their SAFs will be allocated.

But perhaps the funding issue is not as important to students as it may appear to be. In the News’ survey, 76 percent of students said friends or social opportunities in their groups constituted a major reason for their continued involvement. Generally, students interviewed agreed that the social aspect of their clubs or organizations has been one of the most prominent.

Sarah Brandt ’17 exemplified this sentiment about her a cappella group, Slopappella. Brandt started the group with a few friends partially as a joke, she said, adding that though everyone involved loves to sing, no one in the group considered themselves to be good enough for the rigor and prestige of Singing Group Council groups.

But despite the group’s humorous pretenses, Brandt said the real draw to the group is its tight-knit social circle.

“With a cappella especially, you’re with that group for four years and travel around the world together,” Brandt said. “You become a family.”

Brandt hopes to create a close and loving atmosphere for the 15 to 20 members of Slopappella. Though the group did apply for UOC funding to cover new merchandise, she said, the group only received $70, less than half of what they had initially requested.

Brandt’s affinity for the sense of community within her student organization echoes throughout many larger or more established student groups, including the Duke’s Men. Fergusson said that members of the Duke’s Men love to sing, but there is a familial and fraternal nature that keeps its singers committed.

In addition to loving their new friends, students stay in the organizations they are involved in because they are passionate about them. Eighty-seven percent of survey respondents said their interest in the subject of their group was their number one incentive for staying.

This spirit has survived through the decades. Meeske — the dean in charge of overseeing the registration of student groups — was heavily involved in musical groups as a Yale undergraduate himself in the 70s and described his extracurricular commitments as central to his personal development. He met his wife in the Glee Club, he added.

“[Extracurricular life] was to me, as I think it is to many students today, a very, very central part of going to Yale,” he said.

Over 20 years ago, when Gaurav Khanna ’94 was an editor for The Yale Herald, there were financial difficulties just as there are today. Khanna cannot remember any student group that did not suffer from funding challenges.

Still, what he remembers most clearly is working late nights at the publication and pursuing what he loved.

“We just adored being on that paper,” Khanna said. “[The financial troubles] didn’t dampen the enthusiasm and the creation of new organizations. It just showed the spirit of students wanting to do this — you can’t really snuff it out.”