Photography by William Freedberg.

“It’s just your average small town,” said Newtown High School senior Kacey Caplan.

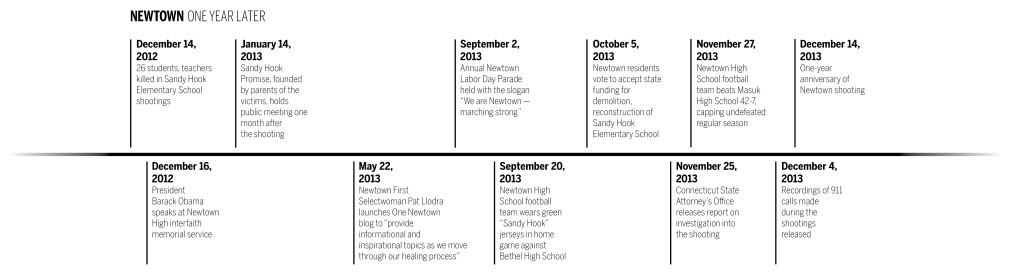

On Dec. 14, 2012, a day residents now call simply “12/14,” the small Connecticut suburb of Newtown forever lost its anonymity. In the aftermath of the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School, media vans descended upon the town, clogging narrow streets, unloading video cameras and knocking on doors to interview neighbors still wounded by the sudden loss of 26 members of their community.

The grief following the shooting rippled through the whole town. Relatives, family friends and neighbors endured 26 consecutive funerals, and the hunger of a nation that could not get enough of their story.

Even now, commemorative green ribbons cover storefronts and windshields. 26 copper stars shine from the roof of the local firehouse, which sits directly outside the elementary school’s main gate. A makeshift sign reading “GOD BLESS THE FAMILIES” is staked into one front yard of a house near the school.

A drive down Main Street, the road at the heart of Newtown’s city square, takes you past shops and a theater that screens movies months after their Hollywood premieres. Edmond Town Hall, a colonial brick building topped with a rooster-shaped weather vane, has stood at 45 Main St. since 1930, a little ways down from a 110-foot tall flagpole that towers majestically in the middle of the street. In the wake of 12/14, teddy bears, flowers and green ribbons obscured its base for weeks. On Newtown’s other major street is the Blue Colony Diner, or just “the diner.”

Places like these serve as ties to a past time before Newtown — like Columbine, Virginia Tech and Aurora before it — became synonymous with tragedy.

“Even if you don’t have a direct connection, just because you did go through everything the town went through, it still affected you,” Caplan said.

As a little girl, Caplan’s high school classmate Emily Pieretti walked the very halls that, in five terrible minutes, changed more than they had in the many years since she left them.

After Sandy Hook, Pieretti followed the beaten path from Sandy Hook to Newtown High — the same path that 12/14’s victims would have likely taken, themselves.

***

“I feel like, definitely, the high school is where the town always gets together,” Pieretti said.

Newton’s seven-school educational district has only one high school, which brings together students from all corners of the town into its largest and most visible community. Newtown High boasts a nationally-renowned marching band, as well as alumni like Olympic gold medalist and Television personality Bruce Jenner.

This fall, the school’s football team gave its students something to cheer about, capping an undefeated regular season with a win against rival Masuk High School. Members of the team sported a “26” decal on their helmets, in tribute to the Sandy Hook victims.

“Everybody was really pumped for our town and for the team,” Caplan said. “We all got excited together — especially for home games — so it was something to look forward to.”

But, as the Friday night lights give way to the December cold, Newtown High will continue to serve as a refuge, of sorts, for a town that has no other center quite like its high school. A Blue Ribbon Award for Schools of Excellence recipient in 2000, Newtown High has always been, if nothing else, familiar and comfortable for its students and teachers.

Amar Agashe ’14, who graduated from Newtown High in 2010, remembers the school as a gathering place.

“It’s basically a common hub for everybody to meet up,” Agashe said. “I feel like a lot of people actually enjoy going to school because they get to see all their friends. It’s not like in a city … you don’t really have that many options. [The high school] is really important for that reason, because it is your primary area of interaction with other people.”

Having this community has been helpful for all members of the community as they continue to search for what else was lost on 12/14: peace.

***

On Dec. 14, 2012, all Emily Pieretti knew was that the lockdown was not a drill.

She recalls sitting on a classroom floor, huddled with her classmates, frantically searching for something, anything to help her figure out what was happening.

“I remember kids just looking at their phones, trying to Google what was going on,” Pieretti said. “The first thing I found out was that there was a shooting at Sandy Hook and that one girl had died. That was just terrible, and we didn’t know if it would get any worse than that.”

Soon enough, word spread that it had, in fact, gotten worse. Fear for their own safety was displaced by disbelief.

“It was so surreal,” Pieretti said. “I was shocked that something like that could happen where I went to elementary school.”

The day after 12/14, the high school was closed.

Over the next few weeks, however, its doors would be open to anyone wanting to come back to what had suddenly become a place of healing for students and teachers alike. Attendance was not taken and classes were optional. Those who did attend could leave the room unannounced to get some air or talk to friends.

For months after the shooting, the school also provided “comfort dogs” for petting in the gym. Board games and movies were available to those who wanted something else to occupy their thoughts.

“They just wanted people to want to go to school and not be afraid of it,” Caplan said.

Therapists were on hand to console anyone struggling to make sense of what had happened, but the topic was generally avoided, Pieretti said

“I took a mental break,” Caplan said. “I laid off all of the [serious] thoughts that I was thinking and just enjoyed going to school.”

For both Caplan and Pieretti, returning to school after the shooting was a way to cope. Both said students relied heavily upon their peers to move through the difficult time together.

Friends found other things to talk about at school, seeking to capture the familiarity they had lost, and they used their shared experience to become even closer.

“We started doing everything together … we would travel in packs just walking to different activities,” Pieretti said.

***

When Agashe returned home from Yale for winter break in the aftermath of the shooting, the familiar community he had left behind seemed completely changed.

“Everything was really quiet. Nobody talked to each other,” Agashe said. “Everyone had this defeated look on their face. People were going about their day to day lives. but they weren’t happy about what they were doing. There was something lingering.”

Eventually, the news trucks packed up to cover the Boston bombings and the government shutdown, but on Dec. 14, 2013, Newtown High is still trying to ease students back into the normal grind.

The comfort dogs stuck around through last spring, and Principal Charles Dumais frequently speaks over the school’s PA system to inspire his still-grief-stricken students. Even the typically-rigid academic expectations have loosened.

“The teachers definitely started to care more after [12/14],” Caplan said. “School was so different after, especially the weeks after. Everything was so focused on us. I feel like things are a little more lenient this year — academically and even with other problems.”

A general openness has allowed students to regain confidence as they distance themselves further and further from the tragedy. But a year later, all remain sensitive to the potential for unpleasant flashbacks.

Caplan recounted a recent episode when the teacher of her Writing Through Film class prefaced clips from “The Godfather” by allowing students to leave the room, given the movie’s heavy portrayal of gun violence.

“I don’t think she would have done that if Sandy Hook hadn’t happened,” Caplan said.

And despite the importance of emergency preparedness, lockdown drills no longer take place in another attempt to avoid bringing back memories of 12/14.

There are also visible changes to the school. Most notably, the number of security guards patrolling the campus has more than doubled since last December and previously-unlocked side doors are now completely inaccessible. To enter the school’s main gate, all drivers pass a guard stationed next to a sign reading “all vehicles must stop,” and can only pass with his approval.

The administrative leniency and tightened security make for an awkward juxtaposition that has Caplan feeling that something is “still a bit off” at Newtown High.

Even so, Newtown High’s focus on its students’ well-being has facilitated the transition back to school — back to the same routine of navigating between classes during the day, working a shift at the local Caraluzzi’s Newtown Market in the afternoon and spending the evenings around the dinner table with family.

“I definitely appreciate everything the school does,” Caplan said.

***

While Leslie Caplan-Block, Caplan’s mother, says she has always been “kind of mother hen-ish,” the events of Sandy-Hook have made her even more aware and on the look-out for potential dangers.

“It definitely does make you want your kids closer,” she said. “Sometimes, when my kids are going off for the weekend, I look at them and think to myself how lucky I am, because I know that anything can happen when they’re out of my sight.”

Students at Newtown High already tend to be independent; they have after-school jobs and drive their own cars. And seniors like Caplan and Pieretti are looking forward to a future of increased independence beyond the town, while indulging a newfound appreciation for what they have at home. Pieretti is graduating this year, but she says she’s not sure how ready she is to leave Newtown.

“I love it here. I’m going to miss some of the teachers and being in a school with all [my] friends,” she said.

Despite the lingering pain of “12/14,” Newtown is still where summer days lounging on Lake Zoar fade into winter nights drinking hot cocoa in front of the fireplace. To Caplan, it’s still just “home.”

Watch this video on YouTube