Yale Daily News

More than 50 years after the Black Panther Party trial shook the Elm City, the trial’s legacies of Black activism and social justice are still alive in New Haven.

From July through October 2020, Artspace New Haven — a non-profit arts organization — showcased an exhibit that recognized the history and legacy of the Black Panther Party trial in the Elm City. The exhibit focused on the party’s chairman Bobby Seale, New Haven chapter founder Ericka Huggins and other party members.

“I felt very empowered, I felt very strong,” Elaine Lester, member of local anti-violence organization Ice the Beef, said of the Artspace exhibit. “It was really interesting … getting to know history, especially because it was [about] women [in the Black Panther Party].”

Lester, who is an incoming first year at Gateway Community College in New Haven, participated in an Ice the Beef video dedicated to Huggins and the women of the BPP that is part of the Artspace exhibit.

Chaz Carmon, president of Ice the Beef, said that filming the video on the New Haven Green — where many New Haven rallies, including the BPP May Day demonstrations, have occurred — was the “epitome of Ice the Beef.” He said the organization encourages New Haven youth to be organizers and activists, just like the Black community members that rallied on the Green over 50 years ago.

And on Yale’s campus, organizations including Black Students for Disarmament at Yale and the Black Student Alliance at Yale continue to carry out community-based initiatives advocating for social justice.

Panthers on Trial

In 1970, BPP members including Seale and Huggins were tried for charges related to the death of Alex Rackley. Panthers members suspected Rackley of being an FBI informant in the age of COINTERPLO — a “Counter-Intelligence Program” created by the Federal Bureau of Intelligence to infiltrate radical groups like the Panthers. Rackley was tortured and killed by fellow BPP members Warren Kimbro, Lonnie McLucas and George Sams Jr., who were convicted of the crime, according to the New Haven Independent and Connecticut History.

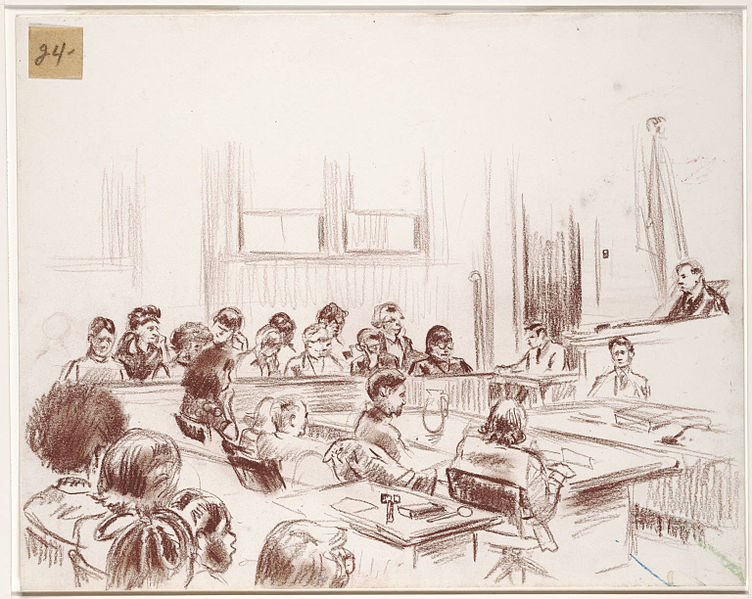

But the trials of Seale and Huggins sparked national attention. The state charged both well-known Panther members with conspiracy to kill Rackley, and prosecutors sought the death penalty. Although Seale was in New Haven at the time of Rackley’s death, neither he nor Huggins was “present during the commission of the murder,” according to the Beinecke collections website. The trials lasted until May 1971, and all but three members — Kimbro, McLucas and Sams Jr. — were acquitted.

Seale’s trial ended in a hung jury and the judge ruled that the state could not retry Seale on the charges.

The relationship between the BPP, COINTERPLO and FBI informants has been reevaluated through the February 2021 release of “Judas and the Black Messiah” — a biographical drama about Fred Hampton and the Black Panthers in Chicago.

“I think the movie was a really powerful and important portrait of the extent to which the Black Panther Party was the subject of a relentless and treacherous and violent campaign on the part of the FBI’s COINTERPLO operation,” Yale Law School professor Elizabeth Hinton told the News. “Black leaders and organizations have long been the targets of government surveillance.”

Hinton, who specializes in the history of policing, said that the movie rightly portrayed COINTERPLO as “one of the most egregious examples of civil liberty violations in U.S. history.” She said that this history was one Americans still need to come to terms with — saying that the incorporation of Black informants into such programs often made them “victims of forms of police violence.”

Hinton also expressed how the BPP “profoundly shaped” Black culture and highlighted the party’s community-based efforts, including free breakfast programs and political education classes. Hinton said such community programs, which are also portrayed in the film, should serve as inspiration for activism today.

May Day demonstrations

From May 1 to May 2 in 1970 — what would later become known as May Day weekend — over 15,000 Yale students, New Haveners and social justice leaders gathered on the New Haven Green to support Seale and Huggins. Activists held up posters that read “FREE BOBBY! FREE ERICKA!” as one of many rallying calls addressing racial conditions in the United States. BPP members from across the country, including Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin of the Chicago Seven, gave speeches on the Green.

A week prior to the mass demonstrations, then-University president Kingman Brewster Jr. issued a directive permitting Old Campus and the residential colleges to collectively house up to 13,000 guests. Residential college dining halls also provided meals to protesters, expecting to feed more than 25,000 people. The University gates remained open throughout the demonstrations.

According to archival coverage from the News, New Haven’s May Day demonstrations were largely peaceful — despite the thousands of protestors and presence of the National Guard.

“We sought to encourage the University … to be supportive of the notion that it was important for the Panthers to be given a fair trial,” Ralph Dawson ’71 told the News in an interview. “And also that it was important that the University step up and do what it can to help its neighbors, which was primarily the Black community in New Haven.”

Dawson is a founding member of the Black Student Alliance at Yale, and during the May Day demonstrations, he was a moderator for the student organization.

Dawson said that BSAY advocated for students to be involved in activism while also being peaceful during demonstrations. He said the organization worked closely with the University administration to “maintain a peaceful atmosphere” during their advocacy.

He also reflected on the important contributions BSAY made to Yale. Dawson said that as a minority group on campus, Black students during the time were “in effect, integrating an institution,” and recalled the role Black student activism played in the creation of the African American studies department and the founding of the Afro-American Cultural Center.

Black activism and lasting legacies

“Just thinking about BSAY, I’m really appreciative of the way it’s evolved,” Eden Senay ’22 told the News. “Our main goal is making sure that Black students feel as if they have a place where they can be safe, seen, and candidly respected.”

Senay is the current co-president of BSAY and said that the organization is currently working on multiple speaker series for the rest of the semester. Reflecting back on the generations of BSAY members who came before, Senay said it was “wonderful” to see the Black student population increase on campus and the many Black student-run organizations focused on social justice at Yale.

Jaelen King ’22 also highlighted the roles of other social justice organizations on campus.

“Fifty years ago, campus was a lot different,” King told the News. “Seeing how many people have looked to do the [social justice] work in the past is inspiring because you know that you’re not alone in the fight, but it’s also frustrating in the sense that these cycles continue to repeat — and so now it’s really working towards how we address that.”

King, who is the president of the Black Men’s Union and the executive director of the Black Students for Disarmament at Yale, said his main goal as a student organizer is to support New Haven. In the BMU, King said members involve themselves in the community by tutoring local middle school students.

He expressed the importance of service and mentorship — in both the Yale community and the Elm City.

“I think activism doesn’t just mean showing up to protests,” King said. “Activism is being actively involved and seeing the community heal and grow. That’s a lot of the work that I’ve tried to accomplish in my time at Yale.”

The first cohort of Black students matriculated to Yale in 1964.

Zaporah Price | zaporah.price@yale.edu