YCBA conversation discusses new book ‘Marking Time’

Editors and authors discuss the encyclopedic account of the material history of early modern Britain through dated objects

Courtesy of Edward Town

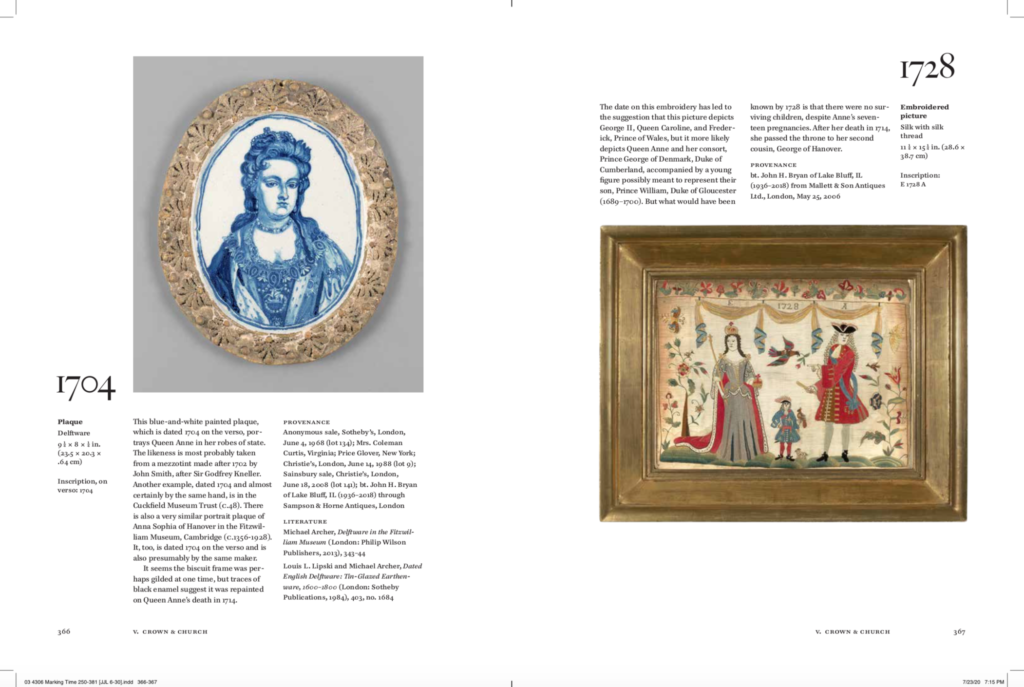

Last Friday, the Yale Center for British Art invited scholars and art historians to a book discussion on a new book titled “Marking Time: Objects, People, and Their Lives, 1500-1800” as part of the Center’s “at home” series. The book consists of a collection of essays by different authors, cataloging early modern British objects.

The discussion featured co-editors Edward Town and Angela McShane, Justin M. Brown GRD ’23, a postdoctoral candidate in the Department of the History of Art and moderator Glenn Adamson. Town is head of collections information and access and assistant curator of early modern at the YCBA, and McShane is an honorary reader of history at the University of Warwick, as well as head of research at the Wellcome Center in London. Both Brown and Adamson authored essays in the book. The book was originally written to accompany an exhibition at the YCBA, which would have displayed the objects described in it. Although the exhibition was canceled due to the pandemic, the contributors still decided to publish the book.

“[The book] showcases just one part of a really remarkable collection of British decorative art, mainly objects, the majority of which are very humble in form and decoration,” said Town. “All of these objects are quite powerful and take us to darker contours of British history and global history.”

“Marking Time: Objects, People, and Their Lives, 1500-1800” consists of seven essays that explore aspects of time and experience in Britain and its colonies. According to Town, 1500 to 1800 A.D. marks a time when Britain underwent tremendous societal and economic change as it gained global prominence through its colonial projects.

But instead of following a chronological order, the sequence of essays thematically begins with objects from childhood and ends with objects relating to death and legacy. Objects in the book are dated to mark pivotal points in people’s lives, which Town described as “important milestones.”

During the conversation, Town told viewers that the objects mentioned in the book come from the collection of the late John H. Bryan, who lived from 1936 to 2018 and was an American businessman. Bryan kept the collection at Crab Tree Farm in Illinois, an American arts and crafts home and estate which was open to the public.

The book builds on McShane’s work as head of research development in the Wellcome Collection in London. In an interview with the News, McShane said she used objects from Bryan’s collection to begin writing a social history of Britain. Later, when Bryan became involved with the YCBA, Town took curatorial lead on the project.

Town said that Bryan’s acquisition of objects stemmed from his ambition to collect one example of each type of early modern object, particularly from England and Wales. Town explained that Bryan did not discriminate in status or style while collecting, which resulted in a “democratic” collection with both ordinary and extraordinary objects — including boxes, spoons, paintings and calendars.

Art experts from around the world came to marvel at the objects. McShane noted that the objects recorded people’s social relationships in their time. Each object is inscribed with names, dates, trades and sometimes life mottos. McShane said that Bryan believed “these things shouldn’t be hidden away.”

“[The objects] spoke to the human experience of the past,” McShane said. “And that’s what intrigued [Bryan] — he was interested in their craft, but he was also really interested in the lives of those people.”

McShane’s own essay in the book focuses on analyzing objects to explore early modern British women at work and at play. For example, according to McShane, a set of snuff boxes depicts women at work but also offers insights into a woman’s independence and social agency.

During the talk, Brown highlighted his interest in understanding how museums grapple with telling difficult histories. His essay looks into the impact that slavery and the Atlantic slave trade had on everyday life and patterns of consumption in early modern Britain. He uses a portrait from the Center’s collections — depicting an unidentified enslaved person and Elihu Yale — to illustrate his point.

“One of the objects that I worked on was an ankle iron inscribed with the year 1733,” Brown wrote in an email to the News. “After looking at several comparative objects, it became clear that this ankle iron was used to mark an enslaved person as property. While its exact context is unknown, it still tells a poignant story about the often-overlooked history of enslaved people in Britain.”

Town said to the News that the book includes a chronology of all listed objects alongside a timeline of significant historical events. This timeline illustrates Britain’s involvement with the world and highlights significant events in global history.

“[The objects demonstrate] the notion that the small, the personal and the everyday have a direct relationship with the largest scheme of historical events,” Town said at the talk.

Brown told the News that he hopes the book will inspire readers to perceive their relationship with objects differently — in a way that is “foundational” to their sense of self and place in history.

The book includes 460 colored and black and white illustrations among its 512 pages. It will be made available for purchase on Nov. 24.

Maria Antonia Sendas | mariaantonia.henriquessendas@yale.edu