If the piano player were better, my mind might wander in his direction, wondering where he lives and who he likes and all that, but he isn’t, and instead I’m sitting in this jazz club reliving our game against Belgium: surprise Euro Cup quarter-final victory, three-to-one. I see the field electric green and the undulating Welsh fans in red and white. It’s the 55th minute, the game is tied one-one, and Bale sends a long ball down from midfield that Ramsey pins to the ground and chips to me right outside the penalty box. I’ve got three Belgians on my ass: De Bruyne, Meunier and Fellaini. I hear a short theme from “Toy Story” on the piano but I don’t care, the pianist is playing too many notes and I Cruyff the shot — I fake a kick with my left leg, pivot on it instead and come round for an open goal and a chance for a left-footed strike. That turn — I see it the same every time. I even stumble out of it before I lift myself up and shoot true and the nation of Wales erupts in song.

I’m smiling like an idiot now but I don’t mind, I never try to hide how I feel about this memory. I can still hear my countrymen chanting my name — Hal! Robson! Hal Robson-Kanu! — as I run a victory lap, my teammates trying to tackle me on the sidelines, my body huge and unreal on the replay screen. I hope this pianist doesn’t see me and think I like him. He’s modern and repetitive; I knew I wouldn’t like it, I don’t know why I came. Often I imagine myself in a shoot-out with Michael Jordan when listening to music like this.

I don’t think too hard about leaving, I just do, and soon I’m through the double doors of the club and out on Division Street where the fading sun is golden and pigeons are waddling at the feet of two boys with floppy haircuts. One boy kicks the air, and the birds take flight, alighting on the crosswalk, where I go now, the parting notes from the piano man taking a final whirl in my head until they slip out forever. I’ve never been to Chinatown before, but I visited other parts of Manhattan when I was a kid. I remember these spiderish fire escapes over the narrow sidewalks and old brick tenements that look good in grime. Though I had thick regular hair then, not an asshole Cristiano Ronaldo undercut like these boys on the street, who have just begun to play “Pokémon Go,” who don’t see me in their pathway, who don’t move aside to let me pass and certainly didn’t weep when Wales fell to Portugal in the semifinals. They probably didn’t even watch the game.

“All the way to Hester Park?” one of them groans. “Not worth it for a Bulbasaur.” I look away to keep my thoughts from turning livid.

Above the shops today I’ve counted one-two-three lithe white women smoking cigarettes out of their big loft windows. There’s another one above the Highline deli, slender wrists and a gossamer T-shirt, staring into the beyond. She’s the kind that probably eats doll food, and below her wrinkled men speak Cantonese and smoke and suck up noodles. I wonder why she lives here.

I wonder about a lot of things here. The borders of Chinatown, for a start. Where are they? Is this the name of the neighborhood on the city books, is it zoned as “Chinatown”? The subway crosses the Manhattan Bridge overpass, rattling the skulls of the cellphone salesmen and fruit vendors who work underneath. A dust cloud tumbles off the edge of the entrance ramp, a line of it caught in a beam of yellow sun, and my eyes prickle at the thought of the invisible rest of it floating into my air. I bump shoulders with an small old woman. She looks at me, says something to herself and rolls her laundry cart away. I don’t like her either — she’s having a go at me. She doesn’t even know who I am. No one here does, no one even does a double take and I wish they would, I’m sure at least someone on this sidewalk saw me score. The day after we lost in the semis, I just up and came here, just to get out of France. Just to stop thinking about Portugal. And now I’m dehydrated and I’m sweating in this city, this big clattering kitchen, everywhere pots falling down the stairs.

On the left by the subway station a football team is practicing in the corner park — their T-shirts say the New York City Strangers. I sit and watch them for a while. They’re about university age, nineteen or twenty, co-ed. They’re doing passing drills. Another team in blue lurks by the sidelines, some spraying bottled water into their mouths, others sitting on the bench staring down at the Astroturf.

“You’ve got to watch her this time, you’ve got to mark her better,” one of the blue team members say to his mate on the bench.

“Yeah, I know,” the mate says, “I know.” He looks at the ground again and violently pumps his leg up and down. He’s in the Zone — a place I know well. It used to be a place worth going to. As a teenager on football training squads I could clear my mind until it was humming with concentration, brilliantly lucid. I played defense back then and had a foil striker on a rival team, Evans, who always managed to scramble past me. When we were seventeen we faced off for the last time. I marked him like mad — I killed my thighs doing it — and for two straight minutes we danced around each other, him not able to pass the ball anywhere and me not able to clear it, until he got so frustrated that he punched me in the stomach. He got red-carded. My mates called me Stomach for a while afterward. This, I think, was my last trip into the Zone as it was when I was young, when I was convinced that any task I was put to must be done. Now that I’m older, the Zone has become something much worse: a place of soft focus, where formless thoughts pick me up, bat me around for a while and set me back down again at their whim. I can feel their fingers closing around me during any breakfast bowl of cereal, when I start to wonder where this bowl is from, where’s the factory where it was made, what’s the history of bowls in the United Kingdom — or even worse, on the football pitch, when I start to pick out the pinheads of shouting spectators and imagine their homes in detail. It’s distraction posing as revelation. It’s taking me over and I don’t like it. I lost to Portugal because of it. I’m done with the Zone. Bad ideas happen there, theories of time and the interconnectedness of things, good grammar goes to die there, it seeps into your waking life I tell you, don’t meddle with the horrors of the Zone.

The Strangers start their game and I start walking back toward the subway. I’m caught behind a sauntering family, and for some reason I’m angry about this, even though I have nowhere to be. The East Broadway station exhales a cloud of people onto the sidewalk. They suck me into their mass and bump me down the subway stairs. I hop the turnstile and walk down to the infernal tracks, and right away I realize my mistake — the best subway stations are the ones that have the uptown and downtown tracks running side by side, with metal pillars between them that form glassless frames of the people standing on the platform across the way. Once, on the way to my mom’s house in London, I saw three teenage boys dancing to a speaker that one was holding to his ear. They didn’t smile much, and they moved like they were walking backwards on a luggage carousel, and as one of them knocked the baseball cap off his mate’s head I only wanted to crawl over the train tracks and dissolve into their side of the pillars, join them without introducing myself, say something about their techno beat and follow them onto their train and down their tunnel.

But East Broadway isn’t the right type of station at all. It’s got one platform between the uptown and downtown lines that seems three stories more underground than it needs to be. People stand around frowning, sweating, soaking in the urine-colored lights, and a woman’s voice shrieks from a fuzzed-out intercom: LADIES AND GENTLEMEN THE BROOKLYN-BOUND F TRAIN IS DELAYED. IT IS DELAYED LADIES AND GENTLEMEN. Seconds later, LADIES AND GENTLEMEN, THERE IS A HEAT ADVISORY IN EFFECT. THERE IS A HEAT ADVISORY IN EFFECT. TAKE CAUTION WITH YOURSELF AND YOUR LOVED ONES. My eyes burn with salt and water. I don’t know who you are, lady. But I hate you.

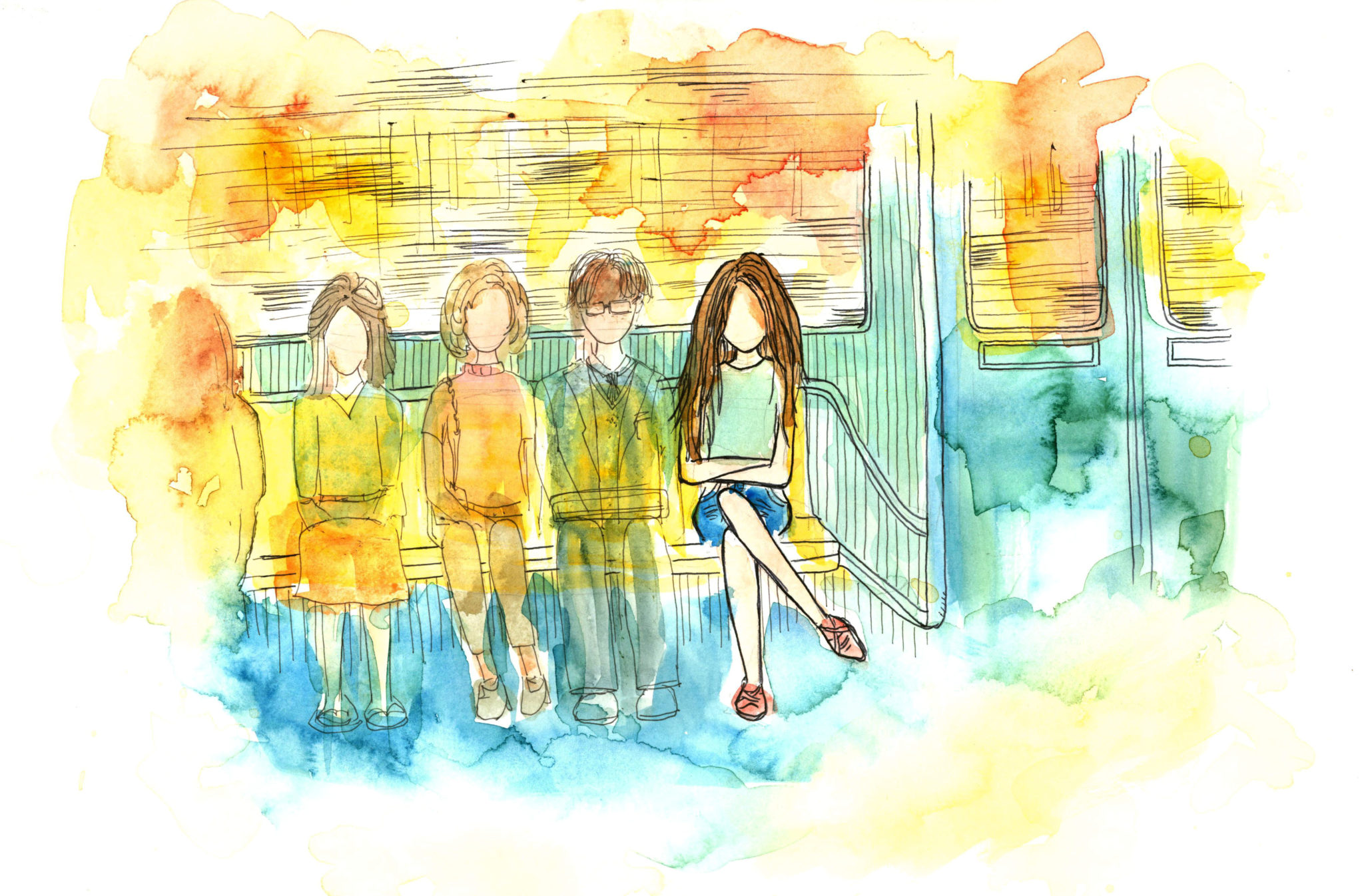

When the train arrives I sarcastically thank it for showing up, but I can’t hear myself over the shrieking. It stops and within seconds nearly all the talking people from the last ride filter into the yellow dinge of the station and let the rest of us compress into the car’s bright white fluorescence. A woman yawns as she heaves herself into a seat; her varicose veins look like tattoos, she wears flip-flops, both her second toes are strange but in different ways. The sweat on my neck turns to ice in the air conditioning. People scratch themselves a lot, and I think back to something I once read about seventy percent of the air in the New York City subway being human skin flakes. I deeply inhale the air full of skin.

Four stops into Brooklyn two girls squirm onto the train as the doors close, sit in front of the window across from me and sigh out words as they catch their breath. “I love him,” one of them says. “Our bodies just fit right into each other.”

“Like a two-piece puzzle,” says the other. The woman next to them laughs into her cell phone. “Yeah,” the first teenager says, scratching her head dreamily, “like a two-piece puzzle.”

We’re out of the dim tunnel now, shooting down the tracks over the pink and brown buildings of the hobbled Brooklyn skyline, some people resting their heads against the windows as the train car fills with sun. I remember other days on other trains, grey rain on windows, stone walls in the countryside, sleeping football players. The girls talk about the guy for a while and then look at the adverts over my head until one of them gets off at Kings Highway. A grown man takes her old seat; the leftover girl shifts her weight. The sun skirts the tops of buildings in the window behind them, illuminating the edges of the girl in gold, catching her flyaway hairs and softening the angles of her chin and shoulders so that her figure dissolves into the moving sky behind her. She stirs, she hums and her fingers curl over the edge of her plastic seat.

That girl is beautiful — I think that in a sentence. She’s got on jean shorts and a tank top, but I can barely see the color of them under the radiance that surrounds her body. She bounces softly with the train. I can’t think of a word for her though I want to, I want to remember what she looks like, but all I think is beautiful beautiful beautiful until somewhere from the back of my mind comes a quiet voice singing, You’re beautiful, you’re beautiful, you’re beautiful, it’s true …

Wait, who is that? Who sings that? I remember — it’s James Blunt, isn’t it? It’s that song, “You’re Beautiful.” I start to hear an acoustic guitar and a string quartet, and the first verse rises gently: I saw an angel, of that I’m sure, she smiled at me on the subway …

Wait, what? Subway? I look away from the girl. I didn’t like that song when it came out. Why the fuck do I even remember it? Why do I have to remember it now? The girl tucks her hair behind her ears. Thank god she doesn’t know what I’m thinking; she has no idea she even looks like this, she’s looking at the opposite wall.

The digital clock overhead flashes 7:13 p.m. The girl leans her head back against the window, straining her neck, exposing a long column of throat.

“Miss, you need to sleep?” the man next to her says, tapping the wall behind him.

“No, it’s okay. I’m getting off soon,” the girl answers. The man asks her where she lives, she says around here. He tells her he’s a desk clerk at the Port Authority and asks her what she does. She says she’s a camp counselor. “I appreciate that,” he says. She smiles a little sadly. They both look ahead for a while, until the girl uncrosses her legs and the man reaches for them. He stops just shy of her, hovering over above the pink blotch on her left knee where her right leg had been resting.

“Oh, look, it’s red.” He sounds concerned, like a grandmother would.

“It’s okay. It doesn’t hurt.” the girl pulls her knee away. They’re quiet then. “You’re Beautiful” comes back in my head. What the fuck? Is this the world I live in now? Where everywhere I look there’s pop songs? More than that, I’m mad about how little control I have over it all. All these stupid songs that I thought were just ambient noise, all this trash in the world, it’s all in me. My brain is full of trash that I didn’t try to put there, and it spits it out at random, surprise synaptic betrayal.

The train eases into the next station. Out go the woman with the toes and some other people that I hadn’t been thinking about, but the girl stays, still so pretty, still there.

“This is a very good day. You know why?” the man says to her.

“Why?” she says.

“Because I met you.”

“Oh.”

“You want to sleep?”

“No, it’s okay. I’m getting off soon.”

“You married? Single? Married?” The girl stares at me.

“I’m married.”

“Your husband. What’s his name?”

We stare and stare at each other. Does she know me? No, that’s not how she’s looking at me. Keep talking girl, please, forget what I might be thinking. What’s his name, what’s his name.

The girl doesn’t blink. “Bastian,” she says. And looks away.