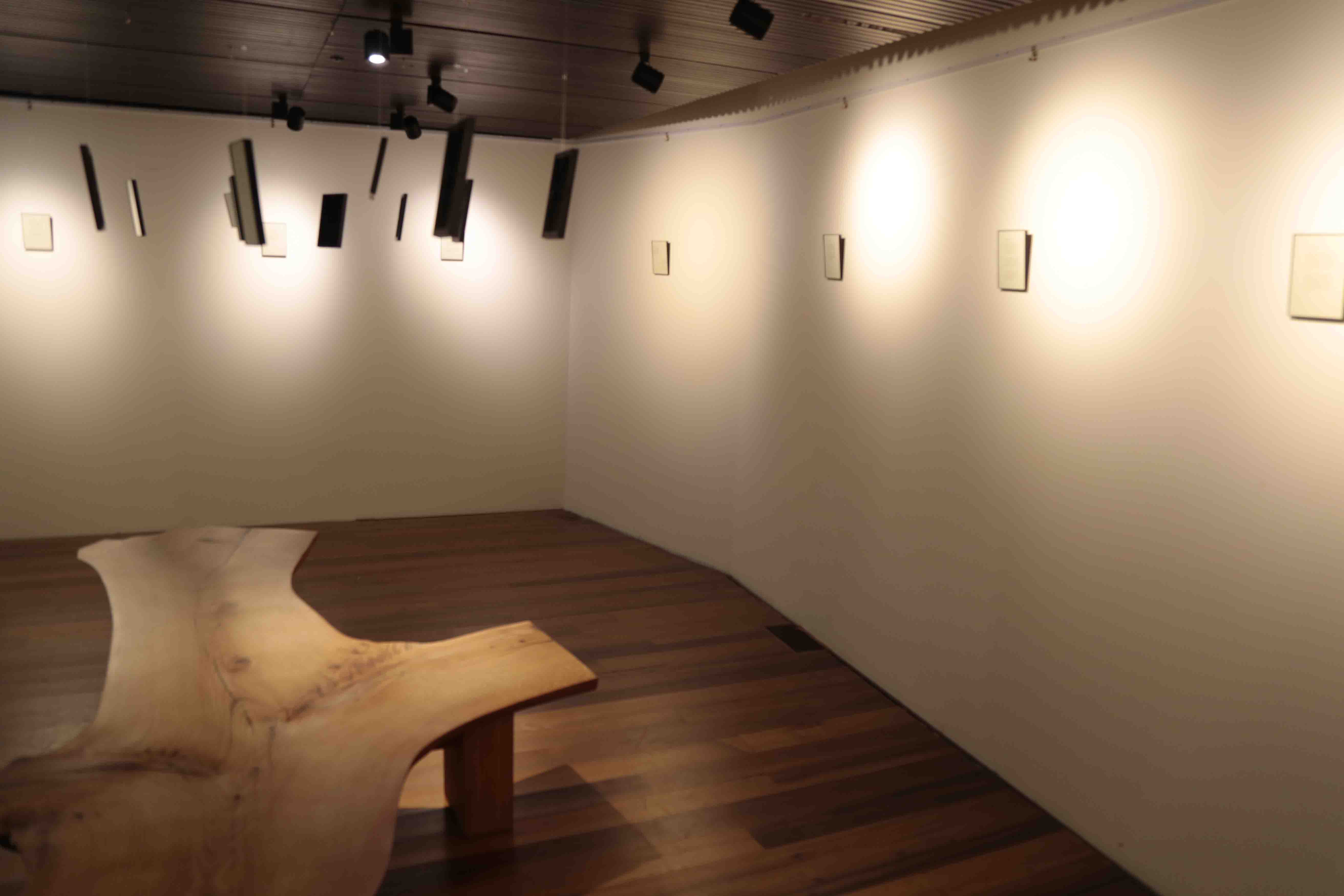

Just steps away from the Ezra Stiles dining hall at the height of the dinner rush, I walk through the door of the Stiles art gallery and into the immersive world of Mindy Le’s poetry. Poems in simple black frames hang on the walls and suspend from the ceiling. The suspended poems sway and twist slightly, lending the exhibit an ethereal quality.

Le, a junior in Ezra Stiles College, had never shown her work publicly before her show “Keeping to Myself” opened. In putting together the exhibit, she wanted to keep her words the primary focus and therefore kept everything else—the font, the paper, the frames—simple. “I didn’t want anything to detract from the words,” she said.

But the poems are not just words; they are also physical artistic objects. The experience of viewing the exhibit is both an intellectual and a visual one. I found myself circling the room multiple times, reading and re-reading, looking from a distance and up close. “It was the first time words were being put up,” said Le, “I wanted to make sure the poems were still visual.”

And they certainly are—the works along the walls are spotlit like paintings in an art museum, and the poems hanging from the ceiling provide visual interest. By dictating the physical space in which the poems are read, Le is able immerse the audience in a physical and intellectual space entirely of her own creation. If you want to read Le’s poems, you must come see them as physical objects in their space, creating an immersive experience for the audience and contextualizing the poems as works of art. Le believes that physically seeing the poems forces the audience to look at each one individually. “You have to physically take steps to look at the next one, and the next one,” she said.

In her written statement at the entrance to the gallery, Le states that the poems were inspired by her general experiences and that neither the exhibit as a whole nor the individual poems are meant to have specific interpretations. Instead, she leaves interpretation up to the reader. “These are my words and your thoughts,” she writes. In a statement that one might expect to help explain or contextualize her poems, Le withholds whatever personal significance the moments she writes about have. Instead, she gives us “words without explanation.” In this way, Le absolves herself of authorial control and places the power (or burden, depending on how you look at it) of deriving meaning, and therefore in a sense defining her poems, in the hands of the reader. In fact, many of Le’s friends had interpretations she herself had never thought of. “The audience will always have their own background that will be taken into account,” Le said, “I like that ambiguity.”

The poems themselves, arranged in chronological order, are bite-sized, encapsulating small moments. Le’s voice is intimate, tender, unassuming—it doesn’t announce itself, but because of this it demands the reader’s careful attention. With each poem I felt as if I were being let in on a secret, even if I wasn’t quite sure what it was. Many of Le’s verses have a dreamy, lulling quality, in lines like “two, three, four fingers running / through the suds and it smells like / roses along the strands of hair” and “Fingers curled around a glass of iced / coffee, tracing a watery comet across / the deep curvature.” But Le’s poems also have an edge and often a wit to them, especially in her somewhat absurdist poems in which the narrator engages in dialogue with animals. “You think you’re so important, don’t you?” a bee tells her in “The story of an acorn” and in “On having a heavy hand,” a cat “told me I was ridiculous for / thinking of such trivial things in times like these.” This edge also often seems self-protective, shielding a sort of vulnerability. In “A way with flowers,” Le writes, “and who are you to believe I even know / my flowers, but I know a rose when I see one because it smells so sweet and looks / so red in your hand, waiting, wanting for / the way your shoes graze the cement.” In this way, Le grabs the audience unsuspecting with her verse: we never know what is just around the corner.

By showing her poems as art, Le literally puts her intimate thoughts on display. Thus, the title of the exhibit is somewhat of a purposeful misnomer. As Le explained, her poems contain personal thoughts she “keeps to herself,” but then, contrary to this idea, publicly displays them. Perhaps the poem “On vanilla beans” says it best: “I imagine the vanilla bean and feel myself splitting down the middle until what I feel is on display and somehow, the words that come out are enough for the time being.” There is certainly vulnerability involved in sharing such intimate work, but so far, Le said, “I’ve been getting a lot of positive feedback.”

“Keeping to Myself” is on display until October 13th.

Julia Gourary | julia.gourary@yale.edu