Preparing for the worst: Immigrant activism in the Trump era

Elm City immigrants are not waiting for the city, state or federal government to protect them from Immigration and Customs Enforcement deportation raids. Instead, they are taking matters into their own hands.

Every Monday, the New Haven Peoples Center on Howe Street is filled with a multinational, multilingual, multigenerational group of locals. From 7 to 9 p.m. each week, a combination of immigrants, Yale undergraduates, Yale Law School students and concerned residents meet to discuss problems pertinent to the New Haven immigrant community.

Though the meetings are conducted mostly in Spanish, there is always someone willing to translate for nonspeakers. Young children chase each other through a matrix of metal chairs, squealing and giggling as their parents discuss issues they hope to solve before their children are old enough to worry about them.

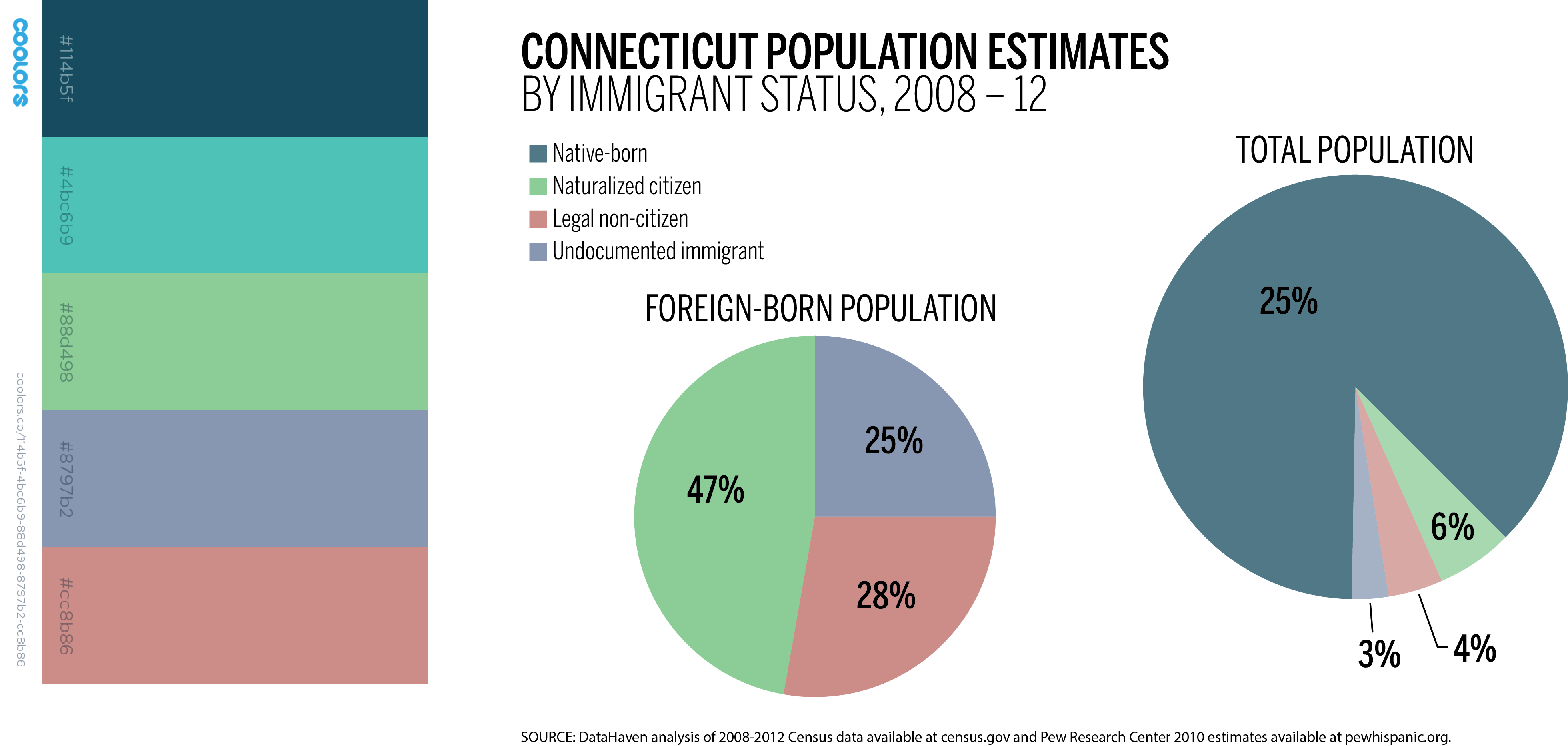

Though the meeting atmosphere is welcoming and jovial, the topics addressed by Unidad Latina en Acción, a local 15-year-old grassroots immigrant rights group, are serious. The group is doubling down on its efforts to protect the city’s approximately 14,430 undocumented immigrants from any potential ICE raids.

New Haven last saw a raid in 2007, when federal ICE officers arrested 32 immigrants in Fair Haven, a predominantly immigrant neighborhood. At the time, ULA’s activist efforts centered on fighting for immigrant rights in the Elm City, but in the decade since, much of its work shifted to focus instead on labor laws, seeking justice for exploited workers. Immigrant rights cases have concentrated on individual deportations rather than raids.

However, President Donald Trump’s ascent to power has led the organization to pivot once, this time to prepare for the worst — massive ICE raids.

On Jan. 25, just five days after being sworn into office, Trump signed his first executive order. “Enhancing Public Safety in the Interior of the United States” called for the hiring of 10,000 new ICE officers and promised to cut federal funding from sanctuary cities like New Haven.

“Right now we live in a very difficult time,” said John Lugo, ULA’s main organizer and one of its co-founders. “We are going back to 2007, which is very painful. It is hard seeing people worry, people coming to us crying. It is heartbreaking.”

ULA’s focus on preventing mass deportations in New Haven — through education, protest and a community response network — reflects a nationwide trend in which grassroots organizations protect immigrants living in the United States. Over the last five months, ULA has channeled a decade and a half of organizing experience into resisting federal threats against the local immigrant community.

PUBLIC DEMONSTRATIONS AND POLICY

ULA’s most visible actions have been their rallies and protests. As a group comprised of roughly 200 volunteers, ULA is able to create noise and engage in civil disobedience without the constraint of institutional rules.

In 2016, ULA held regular demonstrations in protest of Calhoun College’s name and against Thai Taste for wage theft. But in recent months, ULA’s actions have shifted focus from local issues to broader, national topics.

“After Nov. 8, it was all about we need to make sure we are doing the right things to make sure people are protected in case the worse happens,” said Jesus Morales, an organizer with ULA. Morales, a junior at the University of Connecticut, has been working with the group for almost one year.

Perhaps most visibly, in the days following Trump’s election the group organized 500 New Haven residents and Yalies for a march of resistance.

The day immediately following the election, ULA organizers called an emergency meeting in which constituents could share their fears about the future. At that meeting, people were scared, angry and disappointed, Morales said. He said the fear was so widespread even he himself felt afraid — despite being documented.

From this meeting came ULA’s massive march, and a series of rallies in the months after condemned Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies.

The group’s resolutions have not gone unnoticed: ULA has been effective in getting the attention of politicians and policy makers, according to Mayor Toni Harp.

“[ULA] has come to meet with me several times, but the last time we met was right after Mr. Trump was elected president,” Harp said. “They were very concerned about rhetoric around sanctuary cities and said their members feeling insecure. They wanted to make sure we maintain our commitment to our general orders.”

In January 2006, New Haven issued a police general order formalizing six procedures for the New Haven Police Department. These procedures, which ranged from not inquiring about residents’ immigration status to not making arrests based on warrants from ICE, sought to make immigrants feel safer reporting crimes to the police.

But ULA is looking beyond the local general order. Though Morales said the group had discussed advocating for a stronger Trust Act before the election, Trump’s rise to power gave the topic renewed importance, as deportations were not discussed with the same urgency as they are now. The group is working with the Yale Law School Worker and Immigrant Rights Advocacy Clinic to strengthen the Trust Act.

The Trust Act, which passed in 2013 after advocacy efforts from the Connecticut Immigrant Rights Alliance — a coalition that includes ULA and Junta for Progressive Action, a local nonprofit immigrant advocacy group — allows state and city governments to submit to ICE’s requests to detain undocumented immigrants only if they have committed a felony crime.

Megan Fountain ’07, an ULA volunteer, added that the group particularly wants to keep ICE from making arrests in courthouses.

“We have a better version that is even stronger and it’s really urgent that we pass it now because the current government has shown no respect for the United States Constitution,” she said. “The current government has made it clear they are detaining immigrants without due process and so Connecticut has an obligation to protect due process.”

EDUCATION AND RAPID RESPONSE

Beyond public demonstrations and legislative advocacy, ULA is also working on the individual level to educate residents on how they can best prepare for eventual deportation raids.

Since early January, ULA has been hosting “Know Your Rights” classes in conjunction with Junta and the New Haven Board of Education, among other partners. Held in schools, health clinics and community spaces, these classes focus on helping immigrants understand their legal rights, such as not being required to open their doors to ICE agents who do not have a warrant.

ULA members have also attempted to reach more immigrants in the community by going door to door in Fair Haven with “Know Your Rights” information. But this has proved more difficult, according to ULA member and New Haven resident Erik Munoz, as immigrants unfamiliar with the group are sometimes afraid, particularly if a canvasser is white.

To reach more residents, ULA is also creating “neighborhood brigades” by dividing its membership into district-based teams who will have more power in reaching their neighbors and alders. The establishment of the brigades are still in progress, though ULA hopes to begin training brigade leaders at the start of next week.

Lastly, in the case of potential raids, ULA wants to set up a “rapid response network.” ULA has created a hotline number for a 24-hour phone that Lugo has. Beginning next week, the phone will be assigned to seven volunteer ULA members who have committed to taking calls for 24 hours each week. After one volunteer’s shift ends, the phone will pass on to the next volunteer.

If a resident calls in an ICE raid, ULA will first determine the legitimacy of the claim before deciding on further action. The group has received over 100 phone calls since the election from frightened residents who mistook normal police activity as raids, Lugo said.

These false alarms are a testament to the fear that has gripped the immigrant community since the election. Recently, several residents called in after they saw SUVs and officers with canines who turned out to be state troopers training in New Haven, Lugo said.

But if a call does prove to be true, ULA will mobilize a network of New Haven residents who want to help resist ICE. The rapid response team includes members of local social justice organization Showing Up For Racial Justice, members of religious organizations and other concerned community members, including students and lawyers, Lugo said.

Knowing where a raid is occurring will allow ULA to warn immigrants that ICE is in the city.

John DeStefano, who served as New Haven’s mayor from 1994 to 2014, recalled how ICE’s 2007 raid terrified families and harmed immigrant-police relationships. He believes thought ought to be given to meaningful displays of civil disobedience towards federal offices and facilities if they were to participate in retaliatory raids against New Haven.

Co-Chair of SURJ’s Deportation Defense Committee Anna Robinson-Sweet ’11 said SURJ plans to mobilize its members to accompany immigrants to court hearings, attend protests or to go on site to document any potential raids. She said the group already has over 300 contacts, of which at least 50 have committed to going to hearings.

Still, Flavia D’amico, a documented immigrant from Argentina who came to New Haven in 2005, said she has sensed terror in the immigrant community since the election. She occasionally goes to ULA meetings, but many of her undocumented friends are afraid to become involved in ULA as the organization is loud and prominent.

Her friends support ULA’s work, she said, but do not want to risk confrontation with police. She offered the example of one of her undocumented friends, who was afraid to go to the police after her car was broken into for fear of being reported to ICE.

THE PUSH FOR A SANCTUARY CITY

ULA was formed in 2002 by Guatemalan immigrants in New Haven. According to Lugo, a group of about 20 New Haven residents began meeting to oppose a state-level push for a bill that would prnt undocumented immigrants from obtaining driving licences. But the attempt to stop the measure was unsuccessful.

Although they did not succeed in their first endeavor, group members decided to continue meeting to have conversations about problems facing New Haven’s immigrant community, Lugo said. He is now the only one of the original founders still consistently active with ULA. Some have moved on to other forms of advocacy. Others have either since left New Haven or have since been deported, he said.

“It’s really hard to try to stay in contact with that many other people,” Lugo said. “They are moving from one job to another job and one house to another house, and we lost contact with many of them.”

The immigrant community, he noted, is extremely mobile, and ULA loses and gains members often. That mobility leads to one of the group’s main difficulties: It constantly has to train new members who lack institutional memory.

Meetings are open to the public and include New Haven residents from different backgrounds and typically draw at least 30 attendees.

Lugo said he hopes to draw more residents with a new office ULA is renting on Grand Avenue. Beginning this month, ULA will be hosting meetings every week in both locations. The rent for the new space was raised with help from a group of community members who committed to contributing for a year.

Members are encouraged, but not required, to pay $10 in dues each month. Most of those that pay are not immigrants, Lugo said. Since ULA is not a registered nonprofit, it receives donations through its fiscal agent, Shalom United Church of Christ.

In its early years, ULA focused on being at the front lines of the mid-2000s push to make New Haven a sanctuary city, including the creation of a municipal identification card that all Elm City residents could acquire. The ID gives residents a form of identification that can be used in police interactions and to open local bank accounts, even if they are not federally documented.

Kica Matos, director of Immigrant Rights and Racial Justice at the Center of Community Change and deputy mayor under DeStefano, said she and Lugo began discussing ways to advance an immigration agenda in New Haven in 2004. She was the executive director of Junta at the time, and the groups decided to partner to create a pro-immigrant agenda that addressed the systemic needs of immigrants living in New Haven.

Yale Law School professor Michael Wishnie LAW ’93, who heads the Worker & Immigrant Rights Advocacy Clinic said he, his students and other Law School professors have been working with ULA since 2005. Back then, Wishnie was a visiting professor and he had his students help research and draft a joint report with ULA and Junta entitled “A City to Model.” The report included a number of recommendations for the city, including the adoption of a municipal identification card and improvements to police-civilian relationships in parts of New Haven with large immigrant communities.

DeStefano said the report was the genesis for the identity cards, which were officially instituted in 2007. But 48 hours after the card was issued, ICE conducted a retaliatory raid in New Haven during which they arrested 32 New Haven residents, he said.

DeStefano said the raids resulted in increased support for immigrants in New Haven and from New Haven’s representatives, including Joe Lieberman, former chairman of the Senate Homeland Security and Government Affairs Committee.

Since 2007, ULA has continued to support individuals targeted for deportation.

Among those they have assisted is a Connecticut undocumented resident named Pedro, who did not want his last name included in this article for safety reasons. He explained that he fled Honduras because he supported Honduras’ president, Manuel Zelaya, who was deposed in 2009. He had friends who were killed in Honduras, he said.

Pedro was arrested at the border and was detained for 63 days, first in Texas and then in Pennsylvania. During this time he was only allowed out of his cell for an hour a day, he said. He was released when his family members living in Connecticut posted his $9,000 bond.

He came into contact with ULA in 2014 at the recommendation of a friend. ULA has since connected him with a lawyer and his helping him seek political asylum.

ULA has also fought numerous wage theft cases in the past decade by organizing boycotts against restaurants who have committed wage theft and by taking legal action against wage violations. Most of these violations have been committed against low wage, immigrant workers. Some of the most prominent cases ULA has helped workers win include those brought against Thai Taste and Gourmet Heaven.

Harp said, in fact, that her first interactions with ULA were during her time as a state senator, when the group came forward to members of the legislature to discuss issues centered mostly on labor disputes.

ULA has since advocated for stricter laws surrounding wage theft, Harp said, adding that the group was successful in getting the U.S. Department of Labor to investigate several incidents of wage theft in New Haven.

A BROADER MOVEMENT

ULA is not the only immigrant rights groups gearing up to oppose ICE raids. Across the state and country, other grassroots movements have gained traction since Trump’s election.

On such group, Puente Arizona, a grassroots immigrant rights organization formed in 2007 in Phoenix, Arizona. The group advocated for Garcia de Rayos, an Arizona mother who was deported earlier this year.

And Lugo said ULA has based some of its tactics off of work conducted by Puente. He said ULA was not prepared enough when the raids happened in 2007 and that the group feels that Puente’s tactics have been effective at countering ICE operations in Phoenix.

Lucia Sandoval, who directs Media and Communications for Puente, said people across the country have reached out to Puente to learn how to conduct Know Your Rights courses. Puente is also giving out their number as a hotline that immigrants can call if they are in trouble.

ULA operates independently of national charities or political groups and the group has ample representation from the groups, undocumented immigrants and low-wage workers, which it seeks to protect. For ULA members, the fights they are involved in are extremely real and extremely personal.

Salvador Sarmiento, chair of the Washington D.C. Coalition for Immigrant Rights and the national campaign coordinator for the National Day Laborer Organizing Network, said he believes it is critical to challenge the presidential administration on state and local levels. Work in Washington, D.C. is less effective, he said. He explained that NDLON is a network of dozens of community-based organizations across the country. Though ULA is not a member of NDLON, ULA has worked with NDLON in the past.

Sarmiento said ULA sets a good example of what an immigrant rights group should look like. Many people want to be supportive of immigrants and refugees at this time and they should look to established groups like ULA to engage with, he said.

Matos echoed this sentiment. She said she works with grassroots organizations throughout the country, and that ULA is among the most effective groups she is aware of.

“Grassroots organizations and their leaders are the ones on the front lines,” she said. “They are the ones that are most trusted by those whose lives are fragile.”

Make The Road CT is currently fighting for immigrant rights in neighboring Bridgeport. Like ULA and Junta, the organization has hosted Know Your Rights workshops, according to Worker Organizer Luis Luna. Make The Road also aims to pressure the local government to declare Bridgeport as a sanctuary city, he said. Luna added that sanctuary cities are safer for all their residents when immigrants are willing to call and work with police if they witness or are the victims of crimes.

Luna said he got his start in immigration activism when he became a member of ULA in 2007. He has now worked at Make the Road for almost one year.

Despite praise from other activist groups, members of ULA say they are simply doing their best with the tactics available to them.

“I think we cannot really promise anything,” Lugo said of preventing ICE raids. “We have the hope that these ideas that we are putting together will work out. All we can say is if we work together we can make it harder for immigration to really damage the community. But we need to stick together.”

Clarification, April 25: This article has been updated with a more accurate description of what Make The Road CT is doing in Bridgeport.