At the beginning of the 20-minute pose, the model, a student like almost everyone else in the room, took out her readings. She spread the packet between her feet and crouched, resting her chin on her knees. Every few minutes, she flipped a page. The 10 or so people seated in a circle around her, if they caught her movement, noticed it only in the slight twist of her spine, the curls spilt farther past her shoulder, a new muscle betrayed by a shadow. Their focus, after all, was on rendering the figure as it appeared before them, nude.

Yale’s community figure drawing class, Open Life Drawing, runs out of the basement of the Yale School of Art. The program has been a weekly fixture on the arts calendar since 2006, when it was started by School of Art Associate Dean Sam Messer ART ’81. He said the inspiration came from his time at Yale Norfolk summer school, where a complicated enrollment process barred the larger community access to live modeling. Responding to the popularity of the Norfolk class, Messer duplicated his idea that fall: Open Life, which attracts anywhere from a handful of artists to a crowd upward of twenty, has taken place on campus ever since.

At the Royal Academy in London, for example, one room hosts a figure model 24 hours a day. At institutions reserved for the visual arts, a “Life Room” — as the Academy’s studio, fitted with semi-circle benches and a red curtain backdrop, is dubbed — may not be customary, but spaces to draw from a model certainly are. Only recently has figure drawing found establishments outside art academies — a reflection of a wider movement within the art world toward accessibility, among both artists and audiences. Now figure drawing classes can be found at studios and recreation centers from Missoula to Maui, from housewife drawing groups in California to 20-somethings on the second floor of a Paris bar.

On university campuses, figure drawing has long occupied a kind of middle ground. While art students drew from live models regularly, rarely was an invitation extended to the larger community. Now, particularly at liberal arts colleges, figure drawing is open and advertised. Macalaster’s classes are student-run. At Berklee School of Music, attendees compose to the experience. At Brigham Young, models wear bathing suits.

The campus figure drawing class, of course, functions differently from the community one. Materials are often provided. Space is less contested. And the terms of the model’s anonymity change when the room could include peers, professors and friends. Beginner models and artists are more inclined to try figure drawing on campus than at a studio, which is designed more for practicing the art rather than learning it.

It is in this spirit of education that the Open Life flyer — a sketch of a model with the head of an elephant, split-trunked, holding a book open with its toe — welcomes all. With this invitation in hand, and with no background in visual arts, I stopped in on a Wednesday last December. One minute, we were taking sheets of paper and choosing pencils. The next, the model had entered the room. Before any of us had finished steadying our easels — before I had time to formulate any idea of what to expect — the model removed her robe and the session had begun.

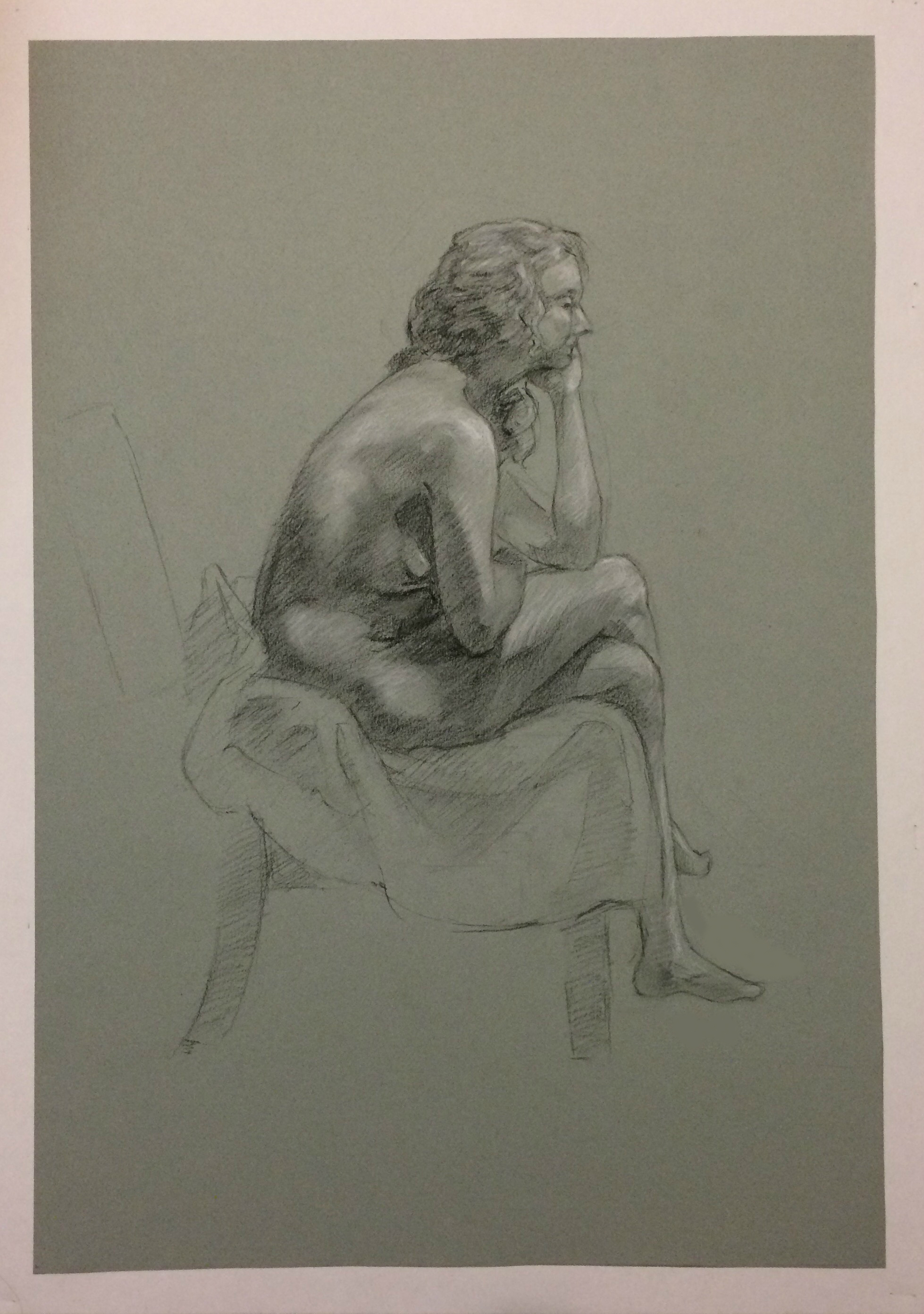

Photo by Kaifeng Wu

—

It used to be that, before an artist was permitted to study a nude, he first had to master facsimiles of figure drawings and engravings, followed by casts of famous sculptures (it wasn’t until 1893 that “lady” students were admitted to life drawing at the Royal Academy). At Open Life, as with all public classes, there’s no such graduation. What used to be the capstone of years of practice is now available to drop-ins. One consequence is a separation of the act of figure drawing from its art-historical tradition — a tradition that, dating to antiquity, has from the start been gendered. Male figures in ancient Greece, celebrated for athleticism and strength, were depicted nude long before women. A carving of a naked Aphrodite in c. 400 B.C., though, launched a new aesthetic of the female form. From that point forward, artists have been revisiting Eves, Venuses and Olympias again and again.

When art major and figure model Adam Moftah ’19 learned to draw a figure, he remembers being told to “focus on your spine. The line of your spine. How that stretches from the top of your head to the bottom of your foot.” Once that line is coursed, achieving likeness is easier with shortcuts. When viewed from the front, for example, the stance between the two eyes is the width of one. An average head is five eyes wide. The width of the mouth is the distance between the pupils. The line between the lips is more important than the outline of the lips — and the shadow at the corner of the mouth is more important than either.

Without instruction, beginners tend to draw from memory rather than by referencing what is in front of them. Trained artists, meanwhile, glance at the model frequently. At Open Life, scanning the room for these types of patterns reveals a range. Seated next to each other are undergraduates and graduate students, faculty and staff, art majors and beginners. One group regularly attends from the Yale School of Medicine, which Messer guesses is residual from the first days of the Yale School of Art — a school partially founded “to teach the medical students how to draw.” Messer believes they come because they “like to draw living people as opposed to cadavers”: it’s true that the body as it appears in art class is especially alive — something capable of holding itself on a podium, expressing through its breath and its blush.

The teaching assistants who run Open Life offer limited correction, if any at all. Mohammad Mohsin, who supervises some of the classes, said he has encountered both experienced drawers and first-timers who attend Open Life “to enjoy drawing with charcoal and different kinds of pencils.” Mohsin himself is from Saudi Arabia, where figure drawing is effectively forbidden. He attended his first session with a live model at art school in Oregon, where he remembers being told he had to be 18 years old to enter — an age requirement notably excused by Yale’s Open Life. After all, one of the best artists in the class, acknowledged by models and other students alike, is 11 year-old Lucas Liu.

Lucas and his mother Lily Shen keep after-school snacks by the foot of their stools. Lily reads while Lucas draws. They commute from New Canaan, about a 45-minute drive each way. They have been coming for a little over a year, ever since Lucas caught the eye of Messer and other Yale faculty during a lecture at the Yale University Art Gallery. There, as part of an exercise, Lucas sketched a Giacometti statue — as he worked, his drawing started attracting a crowd of adults. Lily contacted Messer afterward to ask about opportunities for her son, and Messer replied enthusiastically and invited the mother-son pair to Open Life. The following week, they were back in New Haven, snacks in hand.

The first time he saw a nude model, Lucas’s face blushed. Though shy at first, he did not hesitate once he started drawing. “[He] immediately got into the drawing mode and was just wonderful,” Lily recalled. “And now he’s very used to it.” He’s come to develop a taste of his own, enjoying especially muscles and draperies. His figure drawing, Lily says, is very classical. He prefers drawing the male form because “he adores Michelangelo” — an artist he copied on their last five-week tour of Europe (“My god, before he saw David, he dreamed about this sculpture”), which his mother booked for Lucas to experience the European masters. They’ve done a number of such pilgrimages, including one to China, when Lucas’s interest in Buddha sculptures brought them into every temple they passed. “Do you see how beautiful they are?” he asked in front of every statute, with such awe that Lily wondered if he would become a monk one day.

It’s common for Lucas to obsess over his subjects like this, Lily says. His current passion is drawing football players; although he’s never attended a game, he practices on scrap paper during recess — each sketch, like the ones he does in Open Life, takes two to three minutes. In New Canaan, Lily says athletics like football take precedence over art: the town has witnessed a cancellation of the art history program at the high school, as well as a scaling back of gifted art resources. Silvermine Arts Center, the local studio, was “like a babysitting class” — because of age discrimination, Lily said Lucas would often be denied oil paint or told to “go draw animals instead.”

Open Life, however, has accommodated Lucas’s needs exactly. He doesn’t want to take lessons, which Lily respects, since “lessons can restrict a child’s imagination.” At Open Life, Lucas can learn by example. Their last Wednesday class, one woman was drawing with a Matisse line. Another woman from a few sessions back “was very classical.” Everyone in the room concentrates on different components: the pose, the body, the shading. During breaks, Lucas sometimes goes around to glimpse other drawers’ easels, coming back “raving about what everybody was so good at.” When he picks up his pencil, he tries to incorporate their influence. It’s with their different styles in mind that he starts to draw, tucking his feet on the stool rail, legs not quite long enough to plant firmly on the ground.

—

The first model I drew, in the first pose I drew her, stood like Superwoman: fists on her hips, face turned toward the ceiling. Emma Speer ’17, who has modeled roughly once a week since the end of her sophomore year, is one of the most experienced models at Yale. Open Life is very casual, she said, and sometimes contacts her with “no punctuation, capitalization, text message.” Booking models is usually administered ad hoc through a panlist: requests are sent out, responses solicited and limited communication between the model and organizer takes place beforehand. During her first session, for example, Sofia Braunstein ’18 was not aware she would be modeling with another man. Neither one of them had any prior experience. “He was doing it as a bucket list thing, and I was doing it because I thought it was fun,” she said. “We didn’t realize this until we were both standing outside the art studio in the cold, and we realized, ‘Oh, I guess we’re both doing the same gig?’”

According to model handbooks, failure to inform a model about partners is considered misconduct on the part of the booking agent. But this is not the only example of oversight from the School of Art. Speer said “There have been some seriously awful moments in my life where I’ve just had to be nude without a space heater or any props or anything, not moving, for like twenty minutes,” Fair and respectful treatment of models is non-negotiable, and professional models work together to defend their rights. Guilds exist in major cities. Some have even organized strikes, including one in December 2008, when models stood naked outside of the Paris City Hall culture department to protest a municipal order that called for an end to tipping.

Models themselves have long been seeking more recognition, including possible royalties for their image that, once transcribed, can sell for thousands. Few models in artwork, after all, are ever identified by name — instead, they are referenced as “Nude,” “Nude on the beach,” “Nude in the chair.” Historically, artists claimed to maintain the propriety of the woman with anonymity. John Everett Millais, an English painter and illustrator from the 19th century, even had a trap door in his studio through which models were expected to enter and exit. Female models were occasionally accompanied by their mothers to ensure decency, and some wore masks to hide their identities. Most were paid twice as much as their male counterparts to account for what was considered the extra cost of displaying their bodies.

At $25 an hour, life modeling remains one of the highest paying jobs at Yale. For Braunstein and Speer, the pay is a bonus, not a basis. Speer pointed out that, as it was a hundred years ago, “the extra cost is because it’s nude … which makes it seem like the sacrifice you’re making is that you’re uncomfortable with being nude, so we should pay you to compensate for your discomfort.” The irony is that someone who needs money to overcome their discomfort probably wouldn’t seek the job in the first place. When people are uncomfortable about her nudity, Speer said, it’s because they see her as a naked person and not “a prop.”

“My entire life outside of modeling is me fighting objectification of females, but it’s fine in art classes, as I signed up for it,” she continued. Every other female model I interviewed also mentioned objectification, emphasizing how permission revises the meaning of the artist-model dynamic. With their consent, the interaction takes on a kind of partnership — one where the model is leasing his or her image with the understanding that it will serve not as a subject, but as a source.

—

Conversations around nudity tend to follow a similar script in other corners of Yale. Whatever the context of the nakedness — a classroom, a party in a classroom, a run through the library — the response is usually one of two: “I could never do that,” or “I’ve always wanted to do that.” The second mentality is often part of a bucket list, which confers on all of its items a kind of one-and-done. Bucket list items are meant to have all the freedom of an impulse, where research is optional, as is reflection.

For Braunstein, the repetition is what gives her a new sense of meaning every sitting. She noticed that her composure changes based on her attitude that day, which can vary with her anxiety and depression. “The first time I went modeling I was in a really good place, and so I came in confident and left feeling more confident,” she said. “Meanwhile the second time that I went, the first painting class, I was feeling very vulnerable. I remember not feeling quite sure, and I could tell my body posture, at least when I was going into the room, was a lot more closed.” What she discovered was that she had control over what she exhibited: The manner in which she presented herself was guided by perception, not always reality.

Many models often refer to their yoga experience — Messer even tries to hire models with a background in yoga or dance — and note similarities between the two. Rhoni Gericke ’17, a model for Open Life, likened it to an elaborate body scan. “It’s meditative and straining at the same time,” he said. “I like to think of art modeling and stillness as a form of bodily expression in and of itself: choosing how you occupy space, thinking about the lines it provides the artists to draw from different angles, the shadows you cast.”

When she is on the podium, Speer is either writing stand-up comedy in her head or using the time to mull over modeling. She thinks about how the responses she receives are almost always gendered: girls compliment or thank her after the class ends. Boys either avoid eye contact or try to have conversations, some while she’s mid-pose. Outside of class, Speer finds that people imagine themselves in her position. “There have been several people who have found out that I’m a nude model and been like ‘Oh, I want to do that so bad,’ but don’t actually mean that,” she said. It is the same thing, she added, that she hears about naked parties.

More prominent than figure modeling, naked parties recur often on the Yale bucket list. Often they’re a “my senior year” ambition, as Speer called it. As far as nudity goes, the difference between saying and doing is as thin as a layer of clothing. Nudity, Speer said, is extremely “fetishized” at Yale — unspoken about and unnormalized, but still something people think about aspirationally. As a result, if someone does decide to go to a naked party, “it seems to almost be a come-to moment for them — it’s this level of self-importance that’s projected on everyone when you’re in a naked environment or when you’re talking about nudity.”

Self-importance is the author of most bucket lists — a fault only when it starts reducing every act into one of personal achievement. The result is a kind of decontextualization: removing an action from its original timeline and dropping it, artificially, into our own. Nudity, which involves all of human history, becomes someone’s story from a naked party. Figure drawing, with its controversial past and technical training, is a box checked on a Wednesday. These things, when revised to make sense in a single story, are misleadingly individualistic. Many people, after all, have gone nude or drawn nudes. The shared component of the experience reflects the essence of nudity itself — when stripped of everything else, the body is what everyone has in common.

—

During water breaks, Braunstein likes to do a lap around the room to see how she has been drawn. At the end, she’ll make another round. Sometimes she asks people to take photos of artwork she wishes she could keep. Taking out her phone, she shows me an example of one of her favorites. The painting is beautiful and full of color, and the resemblance is easy to see. It’s also easy to imagine how a collection of similar drawings, informed by different perspectives on the same pose, might together render an even more complete image: The model in the center of the room, with all the possibilities existing in an assembly of viewpoints. A room full of easels.