UP CLOSE:

The political machine that runs New Haven

Last September, as Johanan Knight ’19 talked with his suitemates in his Old Campus common room, someone knocked at the door — a man who looked to be in his mid-20s.

He asked Knight and his suitemates if they were considering voting in the upcoming Ward 1 alder election and proceeded to tell them about the policies of Sarah Eidelson ’12, on whose campaign he was working.

In the days leading up to the election, several more Eidelson canvassers came to their door. Some seemed to be undergraduates, but others looked to be several years older, Knight said. On election day, a canvasser entered Knight’s common room and asked him if he planned to vote in the election. He convinced Knight to do so and then walked with Knight from Old Campus to the post office on Elm Street, where he cast his ballot for Eidelson.

Stories such as Knight’s are familiar to students who were on campus during last year’s election. Eidelson canvassers flooded Old Campus and the rest of Ward 1 throughout last fall, the street corners and courtyards of the ward populated by young adults wielding yellow Eidelson banners. The tactics these canvassers used to squeeze votes out of a largely apathetic student population prompted an investigation into Eidelson’s campaign by Connecticut’s State Election Enforcement Commission, which reviews elections that may have broken state laws on fair campaign tactics.

But where did this groundswell of support come from? Who were these 20-somethings knocking on doors, distributing pamphlets and escorting freshmen to voting booths on behalf of Yale’s current alder?

Answering this question requires diving into the heart of a political machine whose influence permeates every branch of city government, but whose existence eludes most students. The operators of this machine are Locals 33, 34 and 35, the three labor unions that compose UNITE HERE, Yale’s umbrella union organization. UNITE HERE represents about 5,000 clerical, technical and blue-collar workers as well as graduate students at the University.

In interviews, multiple people, including former alder and mayoral candidate Justin Elicker FES ’10, a former alder candidate and a current alder, confirmed that the majority of the city’s alders are beholden to these Yale unions. The current alder — who, in addition to the former alder candidate, wished to remain anonymous for fear of political backlash — said 23 of the city’s 30 alders are backed by UNITE HERE. The Board of Alders is the city’s legislative body and is tasked with passing policies and approving building plans for the city.

According to several sources with deep knowledge of city politics, including Elicker and the current alder, UNITE HERE unions identify aldermanic candidates who will support moves within the BOA that these unions support. Often, these candidates occupy leadership positions in UNITE HERE, such as Eidelson, who is the press secretary for UNITE HERE; Ward 23 Alder Tyisha Walker, the president of the Board of Alders and chief steward of Local 35; Ward 8 Alder and President of Local 33 Aaron Greenberg GRD ’18; and Ward 29 Alder and Vice President of Local 35 Brian Wingate. Some other candidates, like Ward 9 Alder Jessica Holmes, are former union organizers and members.

But most of the candidates UNITE HERE chooses to back do not have direct ties to the union. Instead, they are individuals who UNITE HERE believes will be supportive of their policies.

The UNITE HERE unions use their large numbers of members and organizers to advocate on behalf of these candidates. Union organizers and rank-and-file members work on the campaigns of these select candidates, knocking on doors, organizing campaigns and distributing pamphlets. More often than not, labor-backed candidates ride this swell of support to victory over unbacked candidates.

Eidelson told the News that her canvassers in previous campaigns were mostly undergraduates, with some help from high school students, city residents and UNITE HERE affiliated people. UNITE HERE hires some of its employees, like Eidelson, out of college, meaning some are the same age as the man who knocked on Knight’s door last September. Many graduate students in their twenties also are affiliated with Local 33. All four candidates endorsed by UNITE HERE interviewed for this article said they received canvassing support from people affiliated with Yale unions.

Yale unions’ control over the BOA gives them considerable leverage over the University. Every time the University wishes to build a new construction project, and oftentimes when they have to make renovations to buildings, the University administration must have its plan approved by a vote of the Board of Alders, according to Yale’s Director of New Haven and State Affairs Bruce Alexander ’65. A BOA majority allows Yale unions to filibuster Yale building projects and thus gives the unions a valuable bargaining chip during negotiations with the University.

WHITNEY AVENUE, WALL AND HIGH

UNITE HERE unions’ ability to pressure the University administration via the BOA was evident as recently as last year, when the University tried to build a new science building on Whitney Avenue. The University approached the BOA with its plans in March 2016, but alders delayed their approval until September, according to Director of University Properties Lauren Zucker. She said the postponement delayed about 280 jobs from coming to the city.

Building proposals in New Haven are first reviewed by the City Plan Commission, which is chaired by Local 34 Staff Organizer and Ward 25 Alder Adam Marchand. This commission makes recommendations on proposals, which are then sent to the full body of the BOA for a vote — giving the BOA large say over what can and cannot be built in the city.

(Robbie Short)

Eidelson told the News on Saturday that the BOA voted to delay the project over concerns that it would exacerbate parking problems for many city residents.

“What happens is people often connected to Yale who come to use Yale’s services don’t want to pay for parking so they look for free parking and end up on residential streets,” Eidelson said. “Then people who live there can’t find a parking spot.”

Alders demanded that the University come up with a comprehensive parking plan for the project to mitigate negative effects to city residents.

Alexander said union representatives told his department in May that “they had concerns about parking,” and that his department subsequently “made some accommodations with respect to that issue” in order to push the deal through.

Former Alder Elicker, who ran for mayor in 2013, did not comment on whether or not this move was politically motivated. But he said UNITE HERE-backed alders in the past have used their power over processes that require BOA approval, like the selling of city property, as a political tool.

He cited alders’ decision to sell Wall and High streets to Yale in 2013 as an example. The 17–7 vote of the alders gave the Yale Corporation ownership and jurisdiction over Wall Street between College and York streets, and of High Street between Elm and Grove streets. In this instance, UNITE HERE-affiliated alders voted as a block to approve the deal, Elicker said.

Among those who supported the sale were Walker, Eidelson, Wingate, Holmes, Marchand and Ward 6 Alder Dolores Colón, all of whom are either current or former employees of UNITE HERE unions. Among the seven opposed were former Ward 7 Alder Doug Hausladen ’04 and Ward 21 Alder Brenda Foskey-Cyrus, who later became founding members of the People’s Caucus, a movement within the city government to support alders who were not backed by special interest groups like Yale unions.

But Ward 2 Alder Frank Douglass, a UNITE HERE-backed alder who voted to sell the streets to Yale, said the move had nothing to do with politics and everything to do with practicality.

“Those streets have essentially been in Yale’s possession for many years,” Douglass said. “What business do we have with that street? We weren’t going to put a McDonald’s there or parking meters.”

Ward 22 Alder Jeanette Morrison, who will represent six of Yale’s 14 residential colleges after Benjamin Franklin and Pauli Murray colleges open this fall and who has received support from UNITE HERE in past alder elections, also said it was impractical for the city to hold on to those streets. She explained that they are surrounded on all sides by Yale’s campus, and that it would be impossible for the city to do anything useful with them.

When asked whether UNITE HERE unions have used their power over the building process to twist Yale’s arm in the past, Alexander gave a somewhat cryptic answer.

“The Board of Alders has never stated that was the reason for delays,” he wrote in an email to the News.

MAKING NEW HAVEN WORK

The past few years have been some of the best for Yale’s workers. Sam Chauncey ’57, who served as special assistant to former University President Kingman Brewster between 1963 and 1972 and secretary of the Yale Corporation from 1973 to 1982, said during that time the University had a strained relationship with its employees and their unions, and that strikes were common. But there have been no major strikes in recent years, and unionized Yale employees have seen their wages and qualities of life improve steadily.

Some have attributed these improvements to Yale unions’ ability to leverage their power within the BOA. In 2011, a wave of UNITE HERE-affiliated alders swept onto the BOA, securing a UNITE HERE-backed majority within it. That election year marked the first time UNITE HERE involved itself heavily in city politics.

Only eight of the 20 current alders contacted responded to calls and emails asking for comment.

A year later, in 2012, Locals 34 and 35 signed a significant contract with the University. The contract secured 14 percent pay raises for Local 35 members and 15.35 percent pay increases for Local 34 members over four years. Additionally, Local 35 won a no-layoff clause for four years and the University agreed to establish new programs to connect out-of-work residents with Yale jobs.

When asked how Yale unions were able to cement such a generous contract, Local 35 President Bob Proto said it was likely because of their new political power, according to a 2012 article from the New Haven Independent. Wingate said the contract was “phenomenal” and that he was proud to have been a part of making it happen.

“It’s always great to have the working class moving forward and the economy moving forward,” Wingate said.

Wingate added that he “wouldn’t necessarily” say Locals 34 and 35 were able to establish these contracts because of their influence on the BOA. He explained that these unions have been around for decades and have been securing good contracts for their constituents throughout that time, so the 2012 deal, although certainly impressive, was not entirely unlike past deals.

The current UNITE HERE-backed majority on the BOA has also made headway on public safety and youth service initiatives.

The BOA listed implementing and improving community policing as one of their major focus points in a 2012 declaration of their goals as a board. Under this system, officers are assigned to patrol specific neighborhoods, allowing the officers to develop relationships with neighborhood residents over time and thus to have a finger on the pulse of the neighborhood. In 2016, the city saw 13 homicides, a remarkable improvement over the 34 in 2011. Mayor Harp attributes this success to the city’s commitment to community policing.

New Haven Police Department spokesman David Hartman has also commended the mayor for providing the department with funding for new crime-prevention equipment. One system the NHPD has recently invested in is called ShotSpotter. The system detects gunshots over about 15 square miles of the city and relays information about these shots to officers within minutes.

The current crop of alders is also working to reopen the Q-House, a Dixwell community center that has been closed since 2003, and to build The Escape, another Dixwell community center that will offer after-school programs and tutoring assistance to city children as well as housing for homeless young men.

HISTORY OF THE MACHINE

The unions are not the first group to exert such force over city politics. Since at least the 1950s, different individuals and entities within New Haven have succeeded in taking control of the city’s Democratic Party, and thus city government.

Because the Elm City has not had a Republican mayor since the 1950s, and all 30 of the city’s alders are Democrats, for much of New Haven’s history, whoever has controlled the Democrats has essentially controlled the city.

Chauncey, who has lived in New Haven all his life, said in the 1950s through to the ’80s, chairmen of the city’s Democratic Town Committee held great sway over city government. Chairmen of the town DNC oversee the process by which aldermanic candidates are given the Democratic nomination, and these chairmen used their power to put choice candidates into positions on the board, according to Chauncey.

He said alders then used their power of approving construction projects to twist Yale’s arm. In the 1970s, Chauncey said, the University presented the BOA with plans to build two new residential colleges. But back then, town-gown relations were toxic, and then-DNC Chairman Arthur Barbieri and then-President of the Board of Alders Vincent Mauro Sr. led a charge to have alders disapprove the plans, according to Chauncey.

Mauro was a close associate of Barbieri. After Barbieri resigned in the 1970s, Mauro served as DNC chair until his death in 1987.

Like the DNC chairs of the past, former Mayor John DeStefano was able to consolidate a bloc of alders who supported his policies over the course of his tenure as mayor, Elicker said. From the mid-1990s through the early 2010s, DeStefano used his sway over the city’s electorate to garner support for alders supportive of his policies, and was able to build a strong political base over those nearly 20 years.

This chapter of city politics closed in 2011. The city saw 34 homicides over the course of that year, nearly three times as many as the 2016 figure, and a considerably higher number than in past years. Elicker said many in the city felt deeply disheartened and frustrated with the DeStefano-backed Board of Alders. Eidelson, then a Yale undergraduate, said calls for change within the city grew louder that year.

“That year there was a very, very active conversation around the city about the crisis we were facing and the interconnected crises around crime and violence and joblessness and the effect those have on young people,” Eidelson said. “There was a feeling that some of the alders who had been on the board a long time had gotten somewhat complacent.”

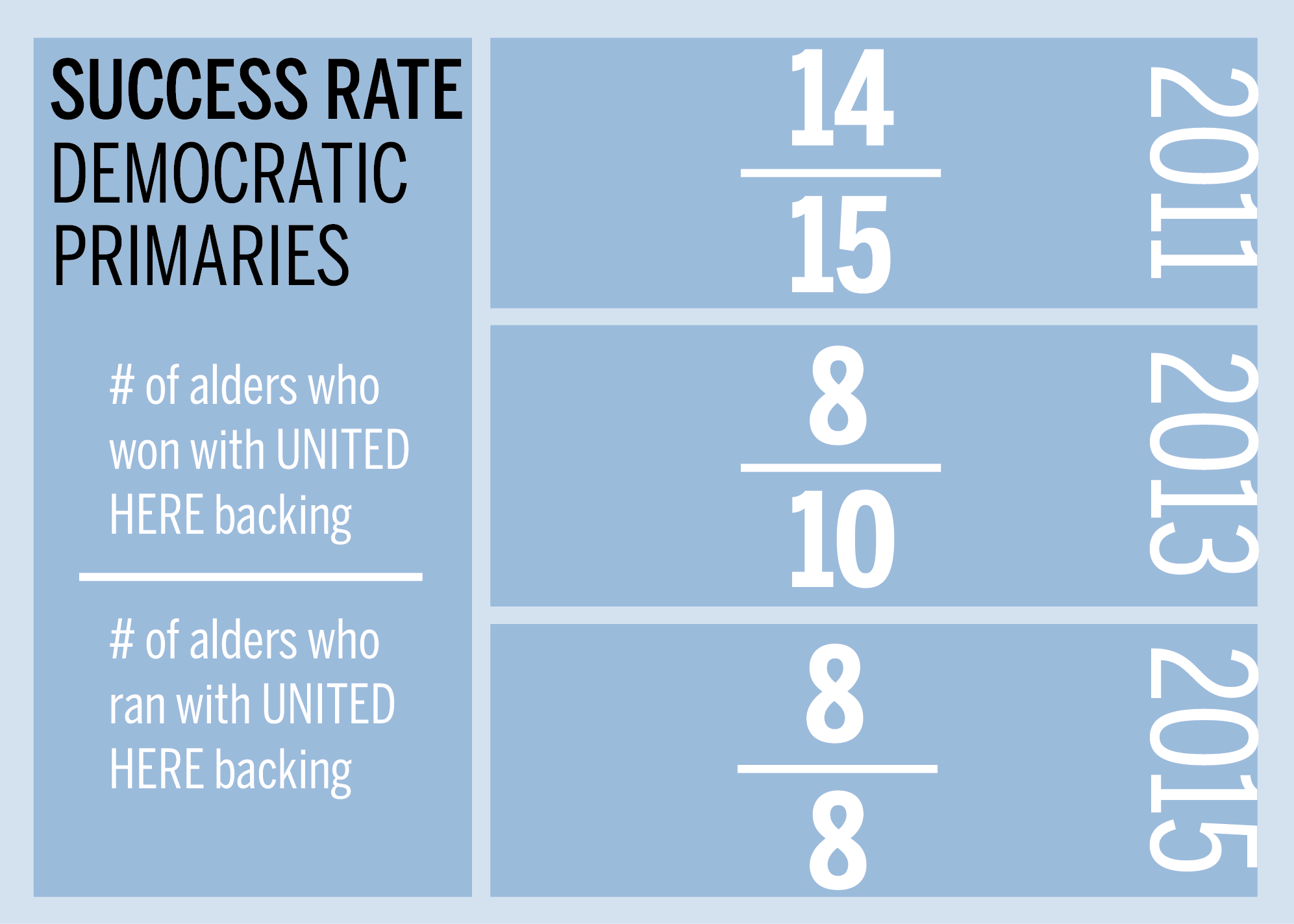

UNITE HERE capitalized on these feelings of frustration in the 2011 aldermanic election. Up until that year, UNITE HERE had not participated heavily in city politics, but in that year’s election, a whopping 15 alder candidates ran with UNITE HERE backing.

Ward 2 Alder and Local 35 Community Vice President Frank Douglass, one of these 15, said he had between 30 to 40 people working on his campaign that year, most of them affiliated with Locals 34 and 35. Morrison, who represents students living in Morse, Ezra Stiles, Silliman and Timothy Dwight colleges, said she had a similar number of people working on her campaign in Ward 22 that year, and that most were affiliated with UNITE HERE.

Several other important labor figures on the BOA, including Eidelson and Walker, also won elections that year with UNITE HERE support.

The Yale union victory was massive. UNITE HERE-backed alders won 14 of the 15 seats for which they ran. The DeStefano regime was out — power had passed to the unions. DeStefano served out the remainder of his mayoral term over the alien BOA, but did not seek re-election in 2013.

DeStefano said he did not seek re-election because he felt he had gotten everything out of being mayor.

Eidelson said it was “unfair” and “disrespectful” to say that certain alders were “controlled” by UNITE HERE. She insisted that alders acted based on their own prerogative, not because they were instructed to do so by the unions or any other group.

But in the wake of the 2012 contract negotiation between Locals 34 and 35 and the University, Proto told the New Haven Independent that his union “controls 20 out of the 30 seats on the Board of Alders.”

PARACHUTE CANDIDATES

Still, the influence that UNITE HERE wields has not gone uncriticized, as union power within city government has been blamed for problems in the city since 2011. One trend some have keyed in on is the success of “parachute candidates,” a term coined by Unidad Latina en Acción member and longtime resident John Lugo. The term refers to candidates who move into neighborhoods months or weeks prior to an aldermanic election, run with UNITE HERE support and win, despite having little connection to the community they now represent.

Kenneth Reveiz ’12, the leader of New Haven Rising, a group partnered with UNITE HERE, became the alder for Ward 14 in March even though he has not lived in the ward for more than a year. After moving to Ward 14, Reveiz became co-chair of the ward’s Democratic Town Committee alongside Mark Firla, a former Local 34 organizer. A short time later, Reveiz won a special election vote of the Ward 14 branch of the Democratic Town Committee, composed of 50 ward residents, to fill the seat of former Ward 14 Alder Santiago Berrios-Bones, who had stepped down a month prior.

Lugo and Sarah Miller, a 19-year resident of the ward who contested Reveiz in the special election, pointed out that Reveiz and Firla changed membership within the Democratic Town Committee prior to the election. Miller claimed that Reveiz and Firla changed the committee’s membership to secure a majority within the committee that would support Reveiz over herself.

But Reveiz wrote in an email to the News in February that he acted in the name of diversity and fair representation.

“We wanted a ward committee that accurately reflected the race, class, language, gender, age and street demographics of Ward 14,” Reveiz wrote.

Democratic Party Chairman Vincent Mauro Jr. noted in a February interview that this rearrangement of the Ward 14 Democratic Town Committee occurred before former alder Berrios-Bones announced his resignation in the middle of his term. The special election that saw Reveiz elected was held in order to fill Berrios-Bones’ spot. Thus, Mauro said, the rearrangement could not have been done with the intention of securing a pro-Reveiz majority for the special election.

But Miller said in February that many of the new committee members with whom she spoke seemed to have no business on it. One, she said, was a young man who said he was “completely apolitical,” and another was a reporter for the New Haven Register. She said she believes Reveiz stacked the committee not necessarily to prepare for a special election, but simply to populate the board with people well-disposed to him.

Lugo told the News in March that he was concerned that Reveiz’ newness to the ward would make it difficult for him to understand the problems and needs of the residents of Ward 14, many of whom are immigrants. He added that, to him, Reveiz’ decision to run appeared completely political.

“He has only been living in Fair Haven for a few months,” Lugo said. “He’s using the community and the political position for the advancement of his alder group.”

Several other current labor-backed alders, including Greenberg, lived in their wards for less than a year before running. But some believe that it is not the amount of time an alder lives in a ward that matters, but rather how well they represent their constituents as alder.

“What’s important is not how long you’ve lived in an area,” Morrison said. “What’s important is your commitment.”

Morrison noted that many who criticize UNITE HERE are former alder candidates who have lost to UNITE HERE-backed candidates. As such, she said, their criticisms should be taken skeptically. Douglass called complaints lodged about UNITE HERE “jealous crap” and said “all this stuff about the unions running our lives” is made up by people angry about losing to UNITE HERE-backed candidates.

But even the staunchest union stalwarts would be hard-pressed to defend the campaign of Ella Wood ’15 in 2013. During that year, Wood was a junior at Yale University and Hausladen served as alder of Ward 7.

Hausladen was not backed by UNITE HERE, according to the former alder mentioned previously who wished to remain anonymous. Hausladen had founded an organization called Take Back New Haven aimed at wresting control of the BOA from the UNITE HERE-backed majority the year prior. Despite the creation of Take Back New Haven, UNITE HERE-backed alders won eight of the 10 elections in which they competed in 2013.

Wood lived in Ward 2 during the early part of 2013, according to an Independent article from that year. But suddenly, days before the deadline to register as an alder candidate, she moved into Ward 7 and registered to run in that ward’s alder race, according to that same article. Wood had not previously lived in the ward. She lost to Hausladen in the Democratic primary 353–251 and dropped out of the race before the general election.

Wood received support from UNITE HERE during her short-lived run for alder, and, like Eidelson, took a job with UNITE HERE after graduating. Wood’s landlord at her former Ward 2 home told the Independent that “it was obvious that someone had put her up to [moving and running in Ward 7].”

Eidelson said she did not think Locals 34 and 35 had asked Wood to move wards and run in Ward 7, but then corrected herself and said she could only speak to her own experience.

Wood did not reply to an email request for comment sent to her Yale email address.

The year after Wood’s loss, Hausladen founded the People’s Caucus with six other alders, including Foskey-Cyrus and former Ward 28 Alder Claudette Robinson-Thorpe. The caucus’ founding charter included seven goals that laid out that alders who belonged to the caucus would, in all circumstances, support good policy, reject bad policy and not engage in “bully tactics” to pressure other alders into supporting policies.

The caucus disbanded months after it was created. Foskey-Cyrus said all the alders associated with the caucus shared the blame for its collapse.

“I can’t say what actually caused [the caucus] to split because at the end of the day nobody can cause it to split but you, so we all caused it,” Foskey-Cyrus said.

Foskey-Cyrus declined to comment on the mission of the caucus or her involvement within it. Robinson-Thorpe felt the same, explaining that she “didn’t want to start anything new.” But according to an Independent article on the caucus, it was founded to offer alders an alternative to the UNITE HERE-backed governing majority of the Board of Alders.

Hausladen stepped away from the BOA and the caucus in February 2015 — just a month after the caucus was officially founded — to become the city’s director of transportation, traffic and parking. Foskey-Cyrus remains on the BOA, but now keeps a lower profile. Robinson-Thorpe lost her seat to Jill Marks in 2015. Local 34 endorsed Marks in that election.

Former Ward 19 Alder Michael Stratton, another of the seven caucus founding members, was challenged by Maureen Gardner in the 2015 Ward 19 aldermanic race. According to Alfreda Edwards, the current Ward 19 alder and a close friend of Stratton at the time, UNITE HERE pulled out all the stops to defeat him.

(Jennifer Lu)

“There were lots of unions people out in the neighborhood, campaigning for [Gardner],” Edwards said.

She added that Stratton had told her that some of Gardner’s canvassers had told him they were from Pennsylvania and Ohio.

Edwards said a UNITE HERE-affiliated alder told her not to support Stratton in the 2015 race. Stratton still managed to win the election, but resigned several months after taking office due to personal scandals. He was later arrested on charges of third-degree assault and second-degree breach of peace.

The current alder mentioned twice before in this article said they feared speaking on the record in case UNITE HERE sent a candidate to their neighborhood to challenge them as retaliation, as some allege it did to Hausladen, or support another candidate in their ward, as alleged in the cases of Robinson-Thorpe and Stratton.

During conversations about UNITE HERE, some of the eight alders interviewed lowered their voices or paused conversation when others walked nearby. Others asked to meet in private places when discussing UNITE HERE.

Walker and Greenberg did not respond to calls, emails and messages asking for comment.

Yale students are, in general, completely unfamiliar with the dynamics of city government. Not a single student unassociated with the News or with the Yale College Democrats knew what Locals 34 or 35 were, let alone their position within city politics. Even now, in the wake of the election of President Donald Trump, when political awareness is stressed by so many, most students do not understand the systems operating within a city that is their home for four years.

It is unclear whether students will take ownership of their role in local politics, and familiarize themselves with local candidates and the groups supporting them. Elections in Ward 1 and Ward 22 are this November. The rest remains to be written.