The Harlem Renaissance was an early 20th century art movement that turned the national eye to marginalized voices in the African-American community. The renaissance occurred in all creative realms, and the exhibit “Gather Out of Star-Dust” at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library showcases this explosion and the ways in which art of all kinds interacted.

The second floor of the Beinecke is ringed with display cases, and though each case is nominally divided by art form, it mixes different artistic media. There are records, playbills, photographs, postcards, prints, sculptures, poems, anthologies and letters. In one cabinet, Aaron Douglas’ collage-like prints are juxtaposed with Langston Hughes’ lyrical poems, both printed on the same thick paper. Underneath, Augusta Savage’s folded sculpture in monochromatic style echoes the words and the image. The exhibit deftly pairs different artists’ works to convey the sense of community within the movement while also giving voice to individual stories.

Placards in front of the works describe the artists’ lives and their introductions to the renaissance. Their personal details are tied in with historical moments, such as the story of Albert Alexander Smith, who was the first African-American to be admitted to the National Academy of Design, and whose delicate etchings of prominent African-American figures showcase the movement’s attempt to reclaim history. The Harlem Renaissance, as the exhibit elaborates, wasn’t just about art; it was also a moment in which libraries were founded to collect letters, scripts, paintings and musical scores from African-American creators.

The exhibit includes many letters, both typed and handwritten. As a poet myself, seeing Hughes’ thought process on paper — which words he crossed out, what he wrote in the margins — was exciting. I felt that I had insight into the personal worlds of great figures, such as Zora Neale Hurston, by seeing their correspondence, often with other artists.

There is one case that shows a letter from W. C. Handy, who was known as the “Father of the Blues,” to Hughes asking him to collaborate on a piece. Seeing these behind-the-scenes moments and the physical papers that the artists touched provides an immersion into the scene of the 1920s, even if the descriptions of the world itself are very brief.

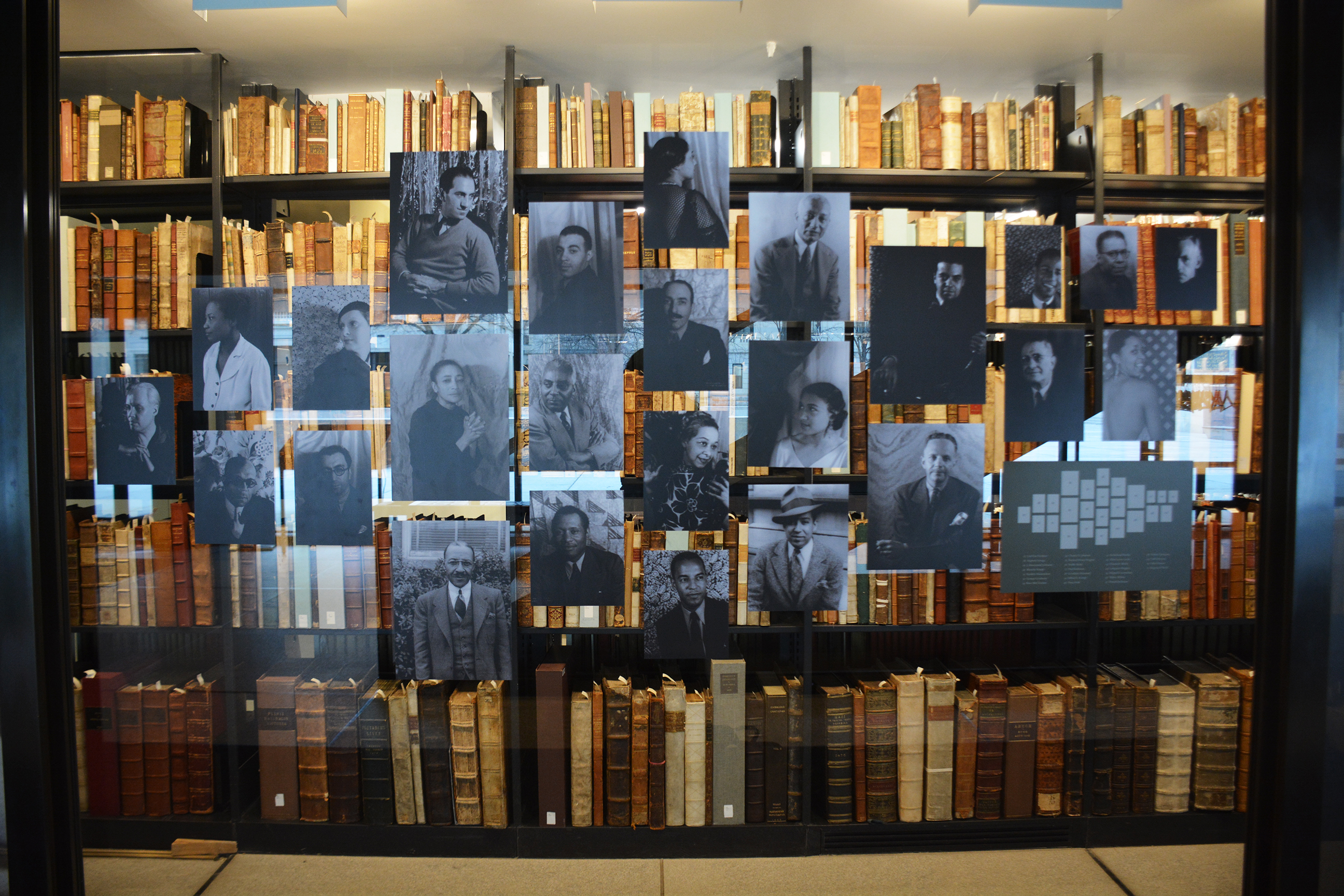

Due to the nature of the exhibition (it’s in the Beinecke) and the fact that it explores so many facets of the Harlem Renaissance, only a few artists of each discipline can be included, and the descriptions of the artifacts themselves are pretty short. However, as a disclaimer, I did realize after leaving that I had missed a few displays on the first floor that explain some of the background of the Harlem Renaissance and its overarching themes. I stopped at a kiosk near the front, however, that had a database of Carl Van Vechten’s portraits (though Vechten himself was white, he was active in the Harlem Renaissance and photographed many of its famous figures). It was filled with images of these individuals and short biographies of their lives, which helped to provide both a look into the expanse of people involved in the movement and each of their stories.

My favorite display was filled with Hughes’ rent party cards. An array of small rectangular cards, all of different colors with varying fonts and details, were laid out as if on a messy desk. Next to them was a placard that explained that African-Americans living in the quickly populating urban centers would sometimes throw music parties in their houses and use the small entry fee to help pay for their exploitatively high rents. The invitations were visually striking and intimate, and their existence was a reminder of the racism that all of the beauty in the exhibit had to overcome.

The exhibit is a breeze to get through, is right in our backyard and offers viewers an opportunity to sample the many aspects of the Harlem Renaissance while also getting glimpses into personal lives and stories.