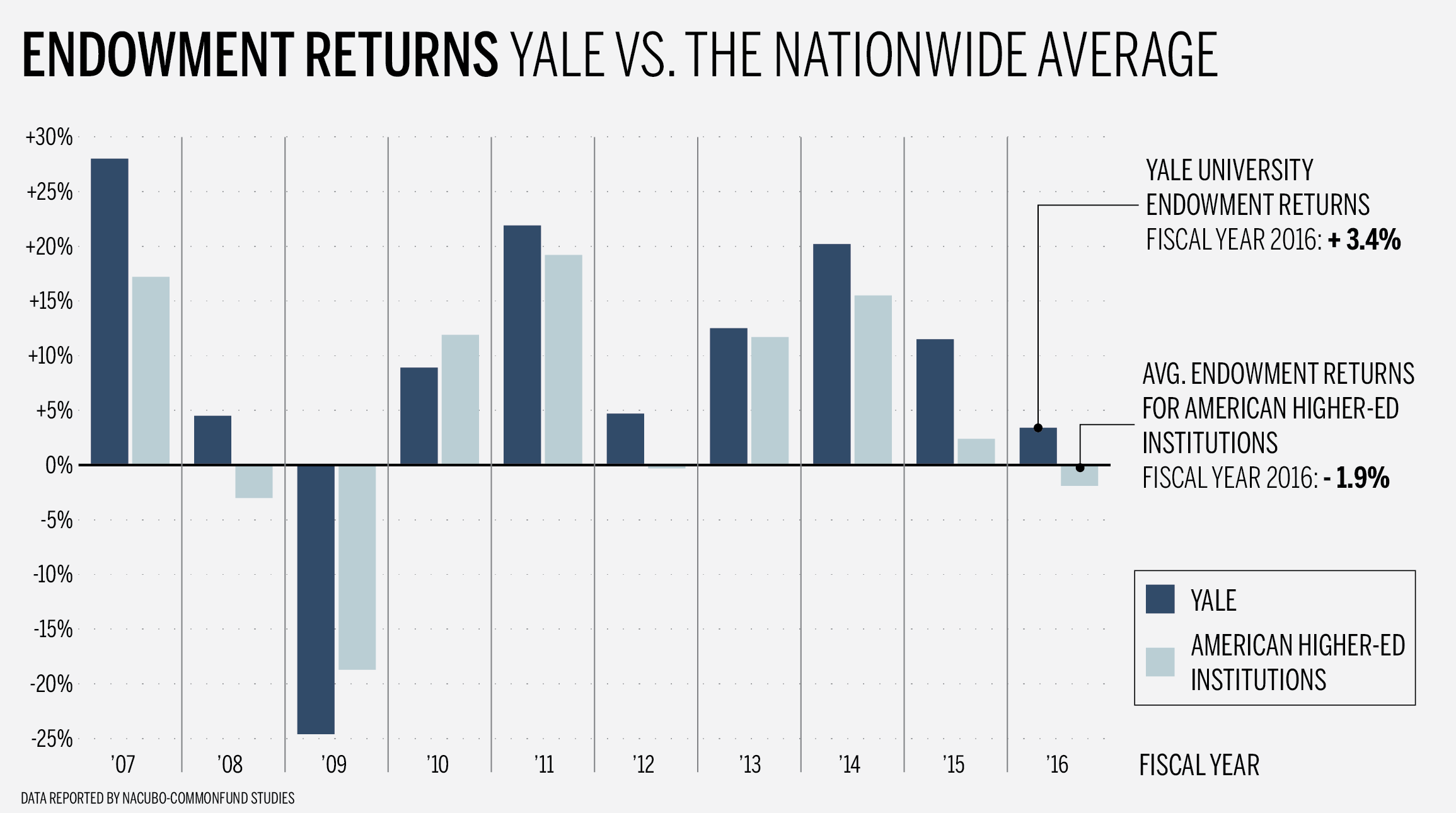

On Tuesday morning, the results of the annual NACUBO-Commonfund Study of Endowments were released, reporting generally bleak investment returns for the endowments of 805 American universities in the fiscal year 2016 that ended last June. But Yale, which posted positive returns in a year when many colleges lost money, remained largely above this trend.

The report, published jointly each year by the institutional investment firm Commonfund Institute and the higher education membership nonprofit National Association of College and University Business Officers, announced an average negative 1.9 percent return on investments nationwide in fiscal 2016, down from positive 2.4 percent in 2015. Yale’s $25.4 billion endowment, however, reported a 3.4 percent return, the strongest performance in the Ivy League and one of the strongest in the nation. However, the report showed worse results on average for the nation’s private universities and those with the largest endowments in comparison to their public and smaller peers.

The study’s 299 public universities reported a negative 1.7 percent return while the 506 private institutions suffered a 2.1 percent loss. The report does not fully explain this discrepancy, but differences between the particular investment portfolios of public and private universities offer potential insight.

In addition to public universities, smaller endowments uncharacteristically outperformed many of the larger endowments like those found at Ivy League institutions. The cohort of greater than $1 billion endowments lost 1.9 percent, whereas the smallest cohort — endowments valued at less than $25 million — lost only 1 percent in returns.

“In a departure from many previous studies, the three smaller size cohorts accounted for a clear majority of the top decile — a total of 65 percent,” the report stated.

The latest nationwide statistics continue a trend of fluctuation reported in the past 10 years. The 2014 NACUBO-Commonfund study reported a 15.5 percent average return; in 2013, it reported a 11.7 percent return and in 2012, a 0.3 percent loss. Returns in the past decade reached their peak in 2011 with universities averaging 19.2 percent and their nadir in 2009 with a 18.7 percent loss on average.

Such drastic volatility from year to year is a natural process, said Bill Jarvis ’77, executive director of Commonfund. Jarvis noted that the yearly fluctuations began with the advent of the 21st century after the dot-com crash of 1999–2001.

“One of the things we can’t control is what the market will give us,” Jarvis said. “Every year has its own story.”

The goal, Jarvis said, was then to minimize risk instead of solely focusing on higher returns.

One way in which Yale and many other universities minimize risk is to create diversified investment portfolios. Among Yale’s portfolio are investments in asset classes including venture capital, natural resources, real estate and fixed income.

Endowments vary, however, in the amount of investments they allocate to each component of the portfolio. The study showed that university endowments under $25 million devoted on average 24 percent of their investments to fixed income, whereas the class of largest endowments devoted only 7 percent.

In fiscal 2016, fixed income saw major increases in share prices, partially explaining the relatively better returns of smaller endowments in 2016.

Moreover, public universities invested on average 10 percent of their endowments to fixed income last year, while private universities invested only 8 percent. This difference in investment strategy, combined with the increased value of fixed income, contributed to the relatively better performance of public universities, Jarvis said.

Smaller endowment funds often devote more of their investment portfolios to fixed income simply because many of the alternative strategies that larger endowments invest in — venture capital, for instance — are dominated by these larger funds.

According to Jarvis, many of the smaller endowments “don’t believe they have access to top managers” in these asset classes. This year, fixed income returns averaged 3.6 percent, the highest of all the asset classes, while venture capital declined to 1.5 percent after being the highest-returning asset class of the 2015 fiscal year.

The report also noted that most universities increased spending from their endowments, with the median increase in spending being 8.1 percent. John D. Walda, president and chief executive officer of NACUBO, expressed concern at this trend in the report.

“In spite of lower returns, colleges and universities continue to raise their endowment spending dollars to fund student financial aid, research and other vital programs,” Walda said. “Continued below-average investment returns will undoubtedly make it much more difficult for colleges and universities to support their missions in the future.”

Yale was no exception to this trend, as it increased spending from its endowment by $71 million, marking a 6.6 percent increase from fiscal 2015. Yale’s spending from endowment, 4.5 percent of the endowment’s total value, accounted for 33 percent of the University’s operating budget.

Though Yale increased spending last year, the University’s financial office adheres to a preset spending policy to ensure that spending does not jeopardize the long-term health of the endowment.

“Yale’s Endowment Spending Policy … seeks to balance the twin objectives of providing a stable flow of income to the annual budget while preserving the real — inflation-adjusted — value of the endowment over time,” said Vice President for Finance and Chief Financial Officer Stephen Murphy ’87. “The spending rule has served the University well in balancing these two objectives, and it continues to do so.”

In fiscal 2016, a particularly difficult year for many other university endowments, this spending policy assured that University spending could increase slightly with as little damage to the endowment as possible. The endowment’s value declined by only 0.6 percent.

The endowment value statistic, however, is not the best measure of an endowment’s performance, Jarvis noted. This market value could increase for a number of reasons unrelated to a university’s investment practices. For example, the University of Pennsylvania reported a negative 1.4 percent return on investments in fiscal 2016 but a 5.7 percent increase in the value of its endowment.

As the Penn investments website noted, the increase was largely driven by the growth in its Health System endowment funds due to the recent integration of Lancaster General Health, a health care delivery system.

Though the yearly statistics allow university investment offices to track their progress closely, more popular metrics are three-, five- and 10-year returns, which buffer against potentially drastic fluctuations between individual years.

“While one-year returns are important, many endowment managers use 10-year average annual returns for long-range planning purposes,” the report stated.

When focusing on 10-year returns, the class of largest endowments still reported the best numbers — an average of 5.7 percent. Yale’s 10-year return is 8.1 percent.