Before Javy Baez tossed to Anthony Rizzo for the final out of the National League Championship Series, I had already purchased a ticket home. That’s a sin in the local religion: never assume a good outcome. “Next year,” the Cubs fan’s abiding consolation to this year, was really last year and also the year before. Today’s omniscience always seemed to laugh the longest at yesterday’s hubris. One hundred and eight years of failure taught about as much.

But this year was different. Seven words told the story, more than justifying the expensive round trip from O’Hare to LaGuardia, the weeklong suspension of campus activities at the inopportune mid-semester, the utterly incomprehensible response from friends and faculty who hadn’t shouldered more than a century of false hope, learned anguish and dreams — little boy dreams, indefinitely deferred.

The Cubs are in the World Series.

And that was reason enough to drop everything for a week and head back home.

After all, Ferris Bueller, the prototypical Cubs fan, once warned that life moves pretty fast. You have to stop and look around once in a while before it rolls on by.

Thirty-five years before Mr. Bueller’s day off in the Second City, William F. Buckley Jr. ’50 in “God and Man at Yale” had condemned the University for neglecting God. Having too often neglected Him in New Haven, I reckoned that a pilgrimage home might help lead me to His grace.

Yale, to Mr. Buckley’s chagrin, had no framework for understanding the scale of festivities that descended on the Second City over a cloudy weekend in late October. The Yale-Harvard tailgate, which usually attracts a modest stadium-size of dusty Ivy Leaguers, paled in comparison to the hundreds of thousands who braved a chilly Chicago nightfall just for proximity to the epicenter at Wrigley Field.

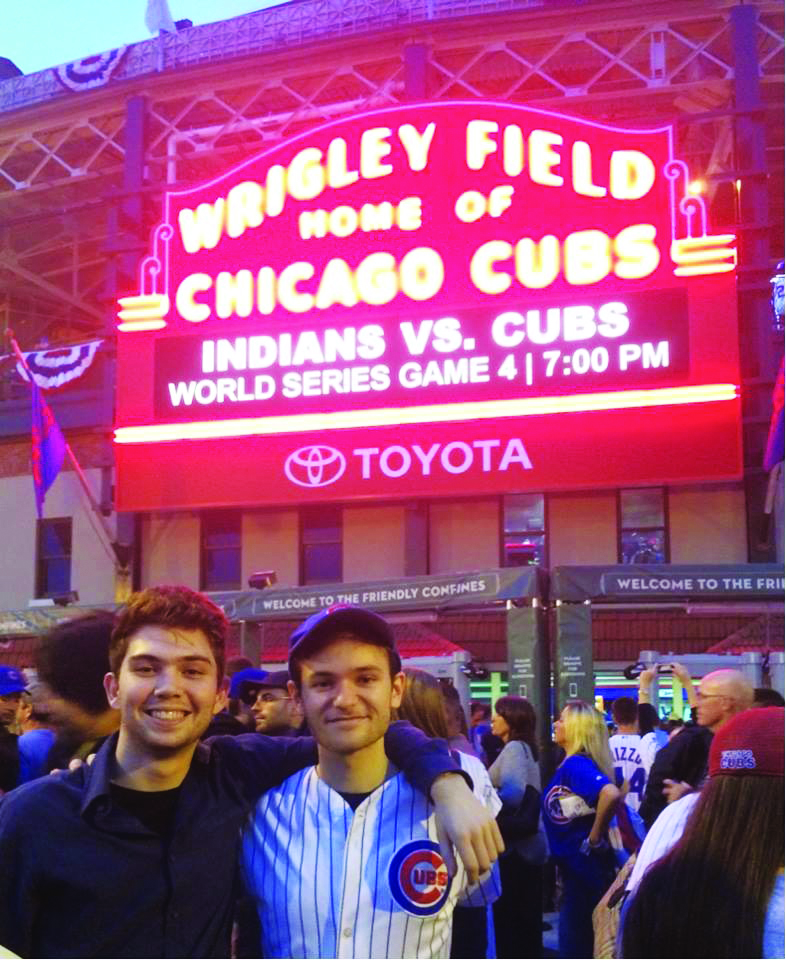

Ticketless, broke and drawn down by a magnetic pull more divine than defensible, a friend and I ventured down to Wrigley Field for Game 4 to celebrate or mourn with the assembled congregation, the huddled masses who, like us, knew that we would one way or another bear witness to history. The stakes were high, and everywhere an ambient tension hugged anxious fans with the cold arms of uncertainty.

The entire city came out to join in the merriment: Children too young to speak, shepherded around by wordless parents too awed to say much themselves; out-of-towners, lucky to admire the formidable communal solidarity; senior citizens in wheelchairs, too close to death to miss the show and the fans, hundreds of thousands milling about, who had dreamed of the moment but never, having come to confront it, could believe its reality.

After all, to root for the Cubs is to vaunt the supernatural. The team plays with a zealous faith that coheres its fanatical followers around a series of revered ceremonies, rituals, symbols and beliefs too decisively spiritual to be thought secular. There are no fair-weather fans — a bandwagoner, of course, needs a bandwagon, and the Cubs haven’t had much of one in over 100 years save a few aborted playoff bids during the Great Depression and the mid-2000s.

So the faithful congregated for one last showcase of spirit to evidence their piety. In every direction within a one-mile radius of the great mecca, Wrigley Field, the streets throbbed with thousands of blue and white pilgrims who apparated at the holy command. Wrigleyville’s famous bars, some 45 in number, charged multiple-hundred dollar covers and still kept lines running out the door. Fans were too drunk on hope and beer to be deterred at the door.

Both liquor and optimism would be handy, for the Cubs bounced off to a pitiable start. By the third inning, they were losing the score and the fans their patience. For a sport notoriously slow, the World Series staggered on a much-reduced tempo that dramatically extended the game time. In a game more influenced by random chance, velocity of play isn’t destiny. But baseball is principally a sport of the mind, subject to self-prophesying feedback loops as easy to escape as quicksand. In baseball, losing begets more losing, and agony only brews more agony, protracting the pain for all but the victor.

An hour into World Series gameplay, the bar we had holed up in drew dead quiet. The enthusiasm, once palpable, had deflated into a muted dejection. First, there was silence. Then boiled the anger — comments muttered between breaths, small tantrums from grown men as each inning passed, fruitlessly, with a sinking heart. Fans began to crack under extended physical and emotional duress. I couldn’t help but wonder if we had cared too much, felt too deeply, when near the sixth a middle-aged woman in a battered old cap and 80s-era jersey strolled out to sob in solitude on Clark Street.

By the seventh, it was clear the Cubs weren’t going to win Game 4. Jason Kipnis, the Indians second baseman who grew up a Cubs fan in Chicago’s northern suburbs, handed Cleveland a six run lead with a loud home run deep into the bleachers behind right field. The wayward son had fatally blasphemed.

On the train out of the city, my friend and I parted through throngs of dour fans eagerly filing home to retire from the shared sorrow. We couldn’t help but laugh, figuring we had witnessed the most quintessential game in the franchise’s history. Expectations, once mile high, had over the course of three brutal hours collapsed with a deflated whimper. The Cubs were down 3-1 in the Series, and we, like most of the city, had resigned ourselves to the usual role hollowed of any further hope.

As we exited the train car, suddenly quite conscious of our matching garb, my friend’s father, a Cubs fan through seventy long years of drought, sent him a brief text:

It’s over. Now we can go back to being true Cubs fans, accepting all we’re good for: defeat.

That defeat was premature. The Cubs would go on to squeak out back-to-back-to-back wins over the three most important matches in franchise history. I endured the make-or-break fifth and sixth games with family, mostly pacing through a stress-induced fog of nervous sweat and anticipation. The two victories felt good insofar as a longer prognosis comforted a patient still convinced she was terminally ill.

The culminatory match, what ESPN later called “the greatest game ever,” was particularly dreadful. The Cubs and Indians seesawed dramatically through 10 innings and a 17 minute rain delay, forcing upon millions an abject cycle of elation and heartbreak that Cubs fans knew well. When the team finally prevailed to win the World Series, four and a half hours after the first pitch, Chicago erupted with a celebration 100 years in the making.

It was a party many thought would never happen. Forget drinking like there’s no tomorrow — imagine letting loose like there was no yesterday.

The Friday after the Series ended, the team hosted a victory parade that spanned the city, from Wrigley Field on the North Side down to Grant Park in the heart of downtown. Five million people, freed to attend when Chicago Public Schools and thousands of businesses decided to close for the occasion, showed up to celebrate en masse. It was the seventh largest gathering in human history — larger than the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893, larger than the election of Barack Obama, a hometown native, to the most powerful office in the world.

Those five million shut down a metropolis for one day to support a ballclub. Most couldn’t even glimpse the caravan of passing buses for longer than 30 seconds till the buses whizzed by, here and then gone.

“Heaven gives its glimpses only to those / Not in position to look too close,” wrote Robert Frost. Far beyond the farthest reach of the collective memory, Chicagoans never imagined themselves in a position to glimpse any more-than-mortal display of sport, let alone for very long. Having now come and gone, the World Series may never again return to home turf.

We faithful knew as much. So we took off the day or the week to stop and glimpse, even for a minute, before heaven passed us by.