Living in Limbo

Living in Limbo: Aymir Holland’s Year in Pre-trial Detention

At 6:34 p.m. on Nov. 27, 2015, the New Haven Police Department received an urgent phone call — Charles Hill, a lecturer in International Studies at Yale, was lying on the ground, badly injured, at the intersection of Bradley Street and Whitney Avenue. According to a press release from NHPD spokesman David Hartman, Hill had been viciously attacked from behind by a group of five men. Gathering his strength, Hill later made it home, where his wife called the police again. An ambulance rushed him to the hospital for treatment of his multiple facial injuries, broken knee and two broken ribs. He was 79 at the time.

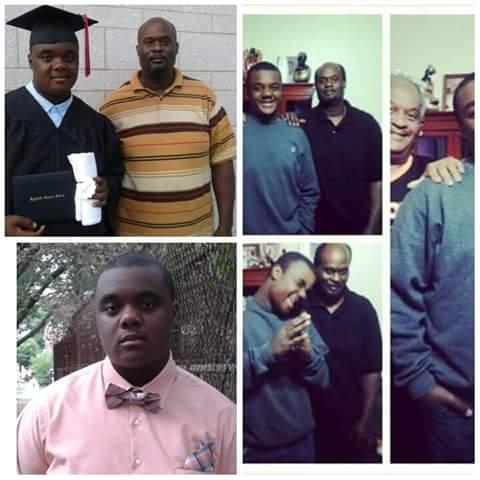

(Courtesy of LaToya Willis)

Hill has since recovered, and over a year later, three of his five alleged assailants sit in prison. Aymir Holland and Kelton Gilbert, who were 16 and 18 at the time of the assault, are detained at Manson Youth Institution for offenders up to age 21; Lawrence Minor, who was 20 during the incident, is detained at an adult institution. The last two of their group remain at large. Each of the three suspects are being charged with five felonies: first degree assault, assault of an elderly victim, first degree robbery, first degree conspiracy to commit assault and first degree conspiracy to commit robbery. The identical felony charges reflect no distinction of the relative levels of culpability among the three defendants, or any special treatment for Holland’s juvenile status.

Having just turned 17, Aymir Holland is the youngest of the accused group. He had never been suspended from school or arrested by the police before. A young black man, Holland’s mother described him as a “gentle giant,” and friends and family mentioned his diverse interests in computer game design, music and football. Now, he faces up to 61 years in prison, as well as the possibility of being tried in court as an adult. But his family remains hopeful that he might be tried as a youthful offender so that even if convicted, Holland would have a second chance: He would not be legally considered a criminal, and the maximum sentence he could accrue would only be four years. Not only would his case stay private, but at 21 the crime would also be stricken from his record, protecting him from the job discrimination that many felons face.

Hill declined to comment due to the sensitivity of the case and the approaching trial. I was also unable to access Holland’s arrest records at the courthouse because of his juvenile status. LaToya Willis, Holland’s mother, said she does not believe he assaulted Hill.

“I’m not going to accept that my son is guilty, because I know that he’s not,” Willis said. “I know my child, and I know that in this situation he didn’t do what he’s being accused of. He was just in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

Holland and the others have yet to be convicted, but with bail set at a quarter million, none of them can afford to go home. So they wait — more than a year and counting — behind bars in pretrial detention.

—

The morning of Hill’s assault, Holland attended a funeral in his hometown of Bridgeport, Connecticut. His best friend had battled leukemia but recently passed away, Holland’s mother explained. The two had played together in their church band, Holland on percussion and his friend on piano.

While the public spotlight is focused on Holland’s upcoming hearing, Willis lingered on the funeral of her son’s best friend. Up till this day, in the midst of his own criminal proceedings, she believes that he has yet to find a time to grieve for his best friend.

At Holland’s best friend’s funeral, Willis couldn’t help but think back to another funeral she attended with her son over six years ago, when the grandmother of Holland’s friend had passed away. At that funeral, Willis recalled, a ten year old Holland walked over to his friend and held her so that she could cry on his shoulders.

“It touched my heart to see him do that on his own at that age,” Willis said. “He didn’t even ask for permission. He saw her hurt, and went to try to console her. That’s how he’s always been. That’s how he is now.”

(Courtesy of LaToya Willis)

Diana Gonzalez-Valeta, a West Haven resident, was struck by this story. On a change.org petition for Holland to be tried as a youthful offender, she blamed the stringency of Holland’s potential punishment on his race.

Almost all activists, family members, and friends I interviewed felt the need to describe Holland as a large black man, an appearance they believed to be the first strike against him. “He can, by his mere size, look threatening, “ said Dave Colton, who mentors Holland in prison as a volunteer through Family Reentry, a Bridgeport organization aiming to stop the cycle of mass incarceration through community-centered interventions.

Those who are familiar with Holland, however, were quick to defend him. “He’s not the kind of big that’s imposing. He’s very friendly. You can see it. He’s got a nice smile,” said Mark Fitzgerald, Holland’s former ninth-grade English teacher.

The accusation against Holland shocked his friends and family. Colton said he found it difficult to imagine that Holland would do anything malicious, and Fitzgerald pointed to the teen’s school record. Holland had never been suspended and was known around school as an anti-bullying advocate. When somebody was being bullied, Holland would always tell the bully to “knock it off,” Fitzgerald recalled.

His mom agreed. “He’s always for the underdog. He doesn’t like to see anyone get bullied or he uses his size to intimidate bullies from bullying people who are smaller,” she said. “He doesn’t like to see anyone hurt.”

And Holland’s kindness has not gone unrecognized. Willis told me that since his arrest, his peers have written letters to the judge commending Holland’s kind actions. By doing so, they hope the trial will be ruled in Holland’s favor.

—

(Courtesy of LaToya Willis)

Holland’s story — a year behind bars in the absence of any conviction — is a sad but familiar one.

“That story sounds unfathomable — that a kid who was 16 years old, now 17 years old, could be in jail for more than a year having never stood trial. It’s sort of mind-boggling,” said Patrick Sullivan ’18, who co-founded the Connecticut Bail Fund with two other Yalies. “Across the United States, there’s about 450,000, maybe more, people in pretrial detention right now.”

A New York Times article written in August 2015 first cited 450,000 as an approximate number of individuals in pretrial detention, including those denied bail and those who are unable to afford it.

Sullivan, Brett Davidson ’16, Simone Seiver ’17 and Scott Greenberg, a researcher at the Yale School of Medicine, formed the Connecticut Bail Fund last year with a grant from the Yale Entrepreneurial Institute. The Bail Fund aims to solve the injustice of money bail by posting bail for clients who can’t afford it.

A 2011 report from the Bureau of Justice revealed that at any time, 60 percent of the prison population is awaiting trial, just like Holland. In Connecticut, about 3,000 people await their trial behind bars at any one time for no reason other than being unable to afford bail. For John Mele, Mentoring Coordinator at Family Reentry, the injustice of pretrial detention cases is a frequent part of his work.

“I just had a young man who was in Manson [Youth Institution] for two and a half years, and who ended up not being found guilty,” Mele said, shaking his head. “Innocent until proven guilty, but for two and a half years he sat in a cell. What kind of system works like that?”

Daee McKnight, who is involved with Family Reentry, said the entire bail system is rife with classicism. “It’s almost like the person is guilty to stay in pretrial detention because they’re in poverty,” McKnight said. “It’s almost like you’re guilty because you’re in poverty.”

Sullivan agreed, adding that in theory, pretrial detention and bail are supposed to incentivize individuals to show up in court. But the current practice has only produced a “two-tiered system of justice,” where the wealthy can pay their bail and go free no matter how severe their crime is, while those without the money are forced to wait for weeks or months in pretrial detention.

And pretrial detention also produces negative long-term consequences. A study commissioned by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation revealed that, on average, those who had been detained before their trial were three times as likely to be sentenced to prison and two times as likely to receive longer prison sentences. In other words, pretrial detention hurts the outcomes of a trial. Michelle Alexander, author of “The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness,” hypothesized in a column for the New York Times that this may be caused by the pressure to take plea bargains, a special deal in which the defendant agrees to plead guilty in exchange for dropped charges or a lower recommended sentence. She pointed out that over 90 percent of criminal trials are resolved in these bargains, which are often coercive in nature.

McKnight, who served 17.5 years of a 25 year sentence, is no stranger to the effects of incarceration on all aspects of life, even after release. Among many factors, he cited job discrimination and his inability to receive money from his mother’s will, because the state extracted a significant percentage of his inheritance to cover his incarceration costs. In fact, in a system where the costs of a criminal record are so high, the effects of accepting any kind of conviction can be crippling.

“We’re supposed to be a second chance society,” McKnight said. “For that statement to become a reality, there are a lot of things we have to do right here in Connecticut…Taking juveniles and trying them as adults is a step backwards to the progress that we’re trying to make.”

—

(Courtesy of LaToya Willis)

Turning down a plea bargain, Holland has stayed in Manson since last November, waiting for his turn to stand a just trial. Meanwhile, his case — and the surprisingly high bail for someone who has never committed a crime in the past — has mobilized the larger New Haven community. Touched by Holland’s situation, Fitzgerald looked for legal support and other ways to financially support Holland’s trial efforts. He tried to contact Yale Law School’s public defender program, but it was no longer in place; he then turned to Quinnipiac, but the public defender program there was tied up; he found Modest Means, a program affiliated with the New Haven Bar Association, but Willis still couldn’t afford one of their lawyers, Fitzgerald explained.

But things started to change when Fitzgerald met Addys Castillo, executive director of the Citywide Youth Coalition. Even though the coalition did not normally pursue criminal justice advocacy, Castillo was swayed by Holland’s story. And when she shared his story with young people in the coalition, she saw an immediate response.

“They were so upset,” Castillo said. “They wanted [Holland’s] story to be told and to see if we could get some type of movement around it. So we held a rally, dinner and dialogue called ‘Justice or Just Us.’”

The movement has only grown from there. Once other young New Haven residents heard about Holland’s case, many decided to get involved. Together, they wrote and published a change.org petition that has gained 626 signatures and started a fundraiser on GoFundMe that has raised over a thousand dollars. Every time Holland went to court for his preliminary hearings, members of the coalition demonstrated in front of the courthouse, calling for the justice system to try Holland as a youthful offender.

The Youth Coalition’s efforts convinced New Haven Mayor Toni Harp to write a letter on Holland’s behalf. And Holland now has a new lawyer — Jason Goddard, who agreed to work on the case on a pro bono basis. Goddard’s presence and the support from the New Haven community have been “such a relief,” Willis said, expressing her gratitude for the extra help.

But the Citywide Youth Coalition did not just change Holland’s case — in fact, the case has transformed and mobilized the coalition into a group of criminal justice advocates. Members have now spoken at the Bail Project about bail reform; they used Holland’s story and his bail of a quarter million to illustrate the ways that the money bail system unfairly targets poor victims. Advisory Board member Cowiya Arona assured me that no matter how the case proceeds, the coalition will continue to fight and protest.

“When I was approached by [Fitzpatrick] and [Willis], it was going to be a passion project on my end to get involved, but then I told the youth about it in the hope that they would want to get involved and I just told them the story and they took it and ran,” Castillo said. “This is really new for us, but we’re really proud of the work that they’ve been able to accomplish.”

(Courtesy of LaToya Willis)

Yet despite the passionate local activism, representation from the Yale community has been largely absent. Yale Police Chief and Director of Public Safety at Yale Ronnell Higgins sent out an email on the day of the attack last November, but in the absence of any University-wide emails, only a few members of the Yale community have followed Holland’s case and even fewer have taken any action.

Sullivan of the Connecticut Bail Fund suspects that the quiet around Holland’s case might be because so much of the Citywide Youth Coalition’s planning occurred over the summer when students were off campus. But he was quick to emphasize that this is not an excuse. “I think it’s troubling that there’s not [more activism],” Sullivan said. “I think this is a perfect example of that Yale-New Haven separation.”

As a leader of the Connecticut Bail Fund, Sullivan has attended several of the Citywide Youth Coalitions events centered around Holland’s case. He shared the names of several other Yale students he had seen at these gatherings. When I reached out, one student declined to be interviewed because she did not feel like she was representing Yale, but was rather engaging as an individual in the New Haven community. Others echoed her sentiments.

Since my interview with Sullivan, the Yale Undergraduate Prison Project, a student ] organization aimed at reducing recidivism and promoting dialogue around mass incarceration, has sent out an email with more information on how to get involved, promising a different future for Yale activism around Holland’s case.

—

On Nov. 30, I sat among the crowd in the New Haven Judicial District Courthouse — Gilbert and Minor were set to appear in court for a pretrial hearing. That morning, family members and friends scattered around the courtroom, waiting anxiously as they sat in the benches. A lawyer approached Gilbert’s family. “He’s okay, he’s okay,” she said. When she left, the courtroom grew quiet again. No judge appeared. Finally, a man approached the security guard in the room.

“Is Lawrence Minor here?” he asked.

The security guard consulted a sheet. “He’s been here and left already. He’ll be back for another hearing on January 5,” the guard finally said.

(Courtesy of LaToya Willis)

And Kelton Gilbert? He, too, will return to the courtroom on January 5. Their lawyers had consulted independently with the judge to put off the hearing, seemingly without the families’ knowledge. The result? Another five weeks in prison. Their constitutionally mandated “speedy trial” did not seem to be approaching anytime soon.

When the families stood up to leave, Gilbert’s mother noticed another family in the room, here for the next hearing that involved another young man who was waiting justice. She waved to a woman, perhaps a friend. The two women hugged — it seemed like they knew each other well.

—

At Manson Youth Institution, the correctional facility in Cheshire, Connecticut where Holland is currently being held, the young men are separated into units called “cottages” based on age, sentence-length and other factors. There is no separation between boys who are already convicted and those still awaiting their trial, Mele told me.

Colton, who mentors at Manson Youth Institution regularly, said he tries to do his best to help the inmates transition.

“I come with my eyes and my ears and then just be receptive to who they are,” Colton said of his usual method. But Holland was a slightly atypical case — he believes the young man has had “a more sheltered life” than the other inmates.

Willis agreed. “Aymir’s in a foreign land right now,” she said. “My son’s not even street smart. He wasn’t raised that way.”

For a long time, Holland was not able to go to church services, the bedrock of his Sunday mornings. Willis said she had to send study materials to her son to “keep up with his spiritual belief.”

Perhaps most difficult was the blow to his education. Attending school is mandatory in Connecticut up to age 17, and that mandate pertains to those who are incarcerated as well. Manson Youth Institution operates its own fully accredited school within the prison walls with over 60 teachers, a library and a computer lab that contains resources for graphic design but with no Internet service, which inmates are forbidden to use. Despite these efforts, students still lag behind.

(Courtesy of LaToya Willis)

“The education in there is nothing compared to the education he was receiving outside. My son has been in charter schools all of his life,” Willis said. “Then he goes to prison and they’re teaching him fifth grade things, and he’s in high school.”

When Jillian Valeta, a member of the Citywide Youth Coalition, heard that Holland was studying Mandarin, she wrote him a letter asking him if he’d like to practice Mandarin with her. He agreed, so she concluded her next letter with some of the new characters that she had learned in her language class.

“And it’s funny but not funny, but [the prison guards] actually wouldn’t give him the letter, thinking that it was gang-related mail,” Willis said, explaining that the security staff at the prison was under the impression that the Mandarin characters in Valeta’s letter were gang symbols. “They actually came to the cell and told him, ‘You can’t have your friends writing you in gang symbols,’ and he’s like ‘I’m not in a gang, what are you talking about?’”

Prison has been isolating, but Holland holds onto the ties that he has from home. In addition to members of the Citywide Youth Coalition, Holland’s classmates take time to write to him regularly. And mother and son talk on the phone on a daily basis.

“I speak to Aymir everyday,” Willis said, holding back tears. “It’s really expensive, but he calls home everyday. It’s about four bucks a phone call, and he calls everyday.”

—

Looking forward, Holland’s mother expressed a mixture of hope and anxiety. Many friends and family described him as an ambitious young man full of potential, but Willis said his future prospects have changed because of the interruption in his education.

“Aymir knows that this situation isn’t his destination,” she said. “He’s ready to come home and pick up the pieces and make something of his life, because this is the time that he would be planning for his life. This situation has stagnated his growth in every area. He’s anxious, I’m anxious and we’re anxious for him to come home and put his life back together.”

Mele recalls a conversation that he had with Holland at their last visit, when he asked Holland what he’d learned in his time in prison. Holland paused and thought for a while. “‘The thing is, we’re all there, we’re all trying to do better in our situation,’” Mele recalled Holland saying.

Holland is scheduled for a court hearing on Dec. 22. At that hearing, the judge will determine whether he will be tried as a youthful offender or as an adult. But it is unclear if the question will be answered then. This is what pretrial detention in Connecticut looks like for Holland and thousands like him — if they do not accept plea bargains, they will have to wait in jail for what feels like an eternity before getting a fair trial.

Still, Holland’s legal team has pledged lasting support for his case.

“We truly care about this young man and we believe in his potential to be a wonderful member of his community,” Meredith Olan said on behalf of Holland’s attorneys. “We are doing everything in our power to give Aymir the best possible representation in his case.”