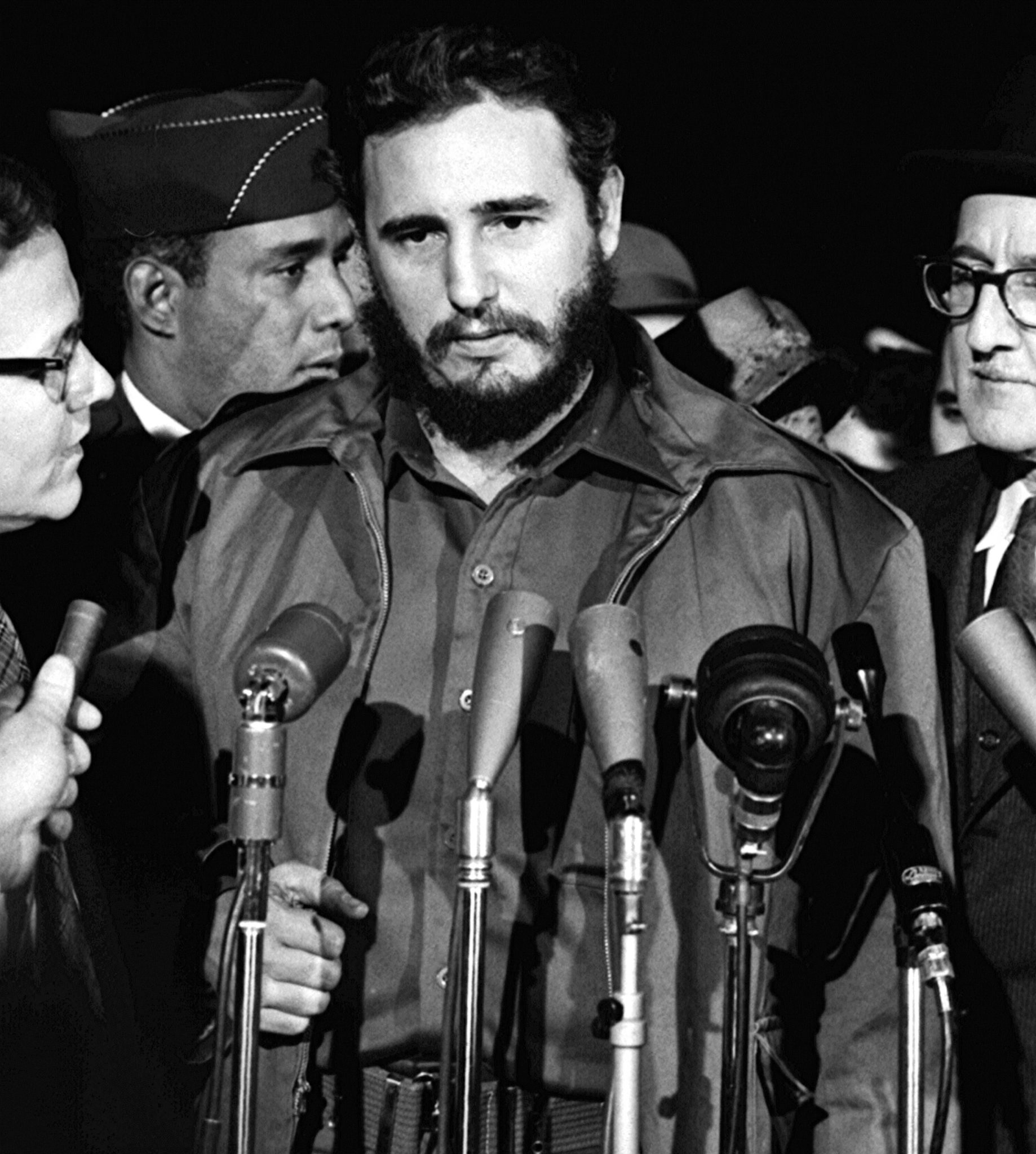

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Fidel Castro, the infamous Cuban revolutionary, died on Nov. 25 at 90 years of age.

News of his death rippled across the international community and was received with mixed public reception: Some lauded his charismatic and fearless demeanor while others highlighted his responsibility in countless Cuban civilian deaths. At Yale, reactions have focused largely Castro’s legacy of state-implemented violence and political misconduct.

The night after his death, over 20,000 Cubans joined to celebrate Castro’s life at the Antonio Maceo Revolution Plaza in Santiago, Cuba. Simultaneously, numerous dissidents were jailed by the Cuban state during the nine-day mandated mourning period. Yale History professor Carlos Eire ’74 GRD ’79 is a Cuban refugee. Along with 14,000 other children, he was airlifted from Cuba in 1962. Eire has published several Castro-centric articles in both The Washington Post and First Things. He has pointed out countless Cuban violent mandates and called out “First World” countries for failing to deromanticize Castro’s legacy. Eire also referenced Castro’s ability to convince millions that he was good, despite widespread suffering. However, he told the News that “[Castro]’s death makes no real difference [now].”

The late Castro stepped down from leading Cuba in 2006, leaving the presidency to his brother Raúl Castro.

The future of Cuba is uncertain, Eire said, adding that Trump’s regressive Cuban policies could harm the state’s tourism industry. According to Eire, an anti-Cuba Trump administration could force the Cuban state to depend more on Europe.

Alex Epstein ’18 criticized the idolization of dictators like Fidel Castro and his contemporary Che Guevara. Epstein also said that his Yale classmates and friends have glorified Castro’s successful liberal reforms in a tyrannical regime, citing statements by the political left.

“His death won’t bring change, but he needed to go before change could happen,” said Epstein.

Angelo Pis-Dudot ’17, a Cuban-American student from Miami, said his studies at Yale into Cuban-exile politics has complicated and contextualized his previous knowledge of Cuba. He highlighted the success of Cuba’s educational and health systems under Castro and denounced the mutually exclusive views of the revolutionary. He also compared Castro’s admirable stance against South African apartheid with Castro’s severe impositions on Cuba.

“His legacy … consists of both systematic violation of human rights under a repressive authoritarian state and real positive gains,” Pis-Dudot said. “It’s similar to praising Chile’s economic successes under Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship without mentioning the fact that he disappeared and killed thousands of Chileans.”

Pis-Dudot said in the wake of Castro’s death, anti-Castro demonstrations in Miami were starkly different from the widespread detainments of Cuban island dissenters.

Miami is a city of immigrants, home to Little Havana Cubans alongside thousands of other Latinos from various countries, such as Venezuela, Honduras and Nicaragua. Regardless of national lineage, Leonardo Sanchez-Noya ’18 said every Miamian has a deep understanding of Cuban-American politics. His grandfather was a political prisoner for 20 years under the Castro regime, he said.

“There’s a really big narrative that people think Cuba is in great shape due to high literacy rates. But in some areas, you have doctors offering to work for a gallon of milk,” Sanchez-Noya said.

Although mainstream media coverage has showcased Cuban islanders in crowds mourning Castro’s death, Sanchez-Noya referenced the silent millions who do not voice otherwise due to fear of state retribution. Both Sanchez-Noya and Eire noted the lack of numbers in dissident voices. Like Epstein, Sanchez-Noya condemned the political left for vilifying revolutionaries like Castro and Guevara but recognized a lack of information as a prominent culprit.

“I just have to remember the phrase: ‘Don’t attribute to malice what can be attributed to ignorance,’” Sanchez-Noya said.