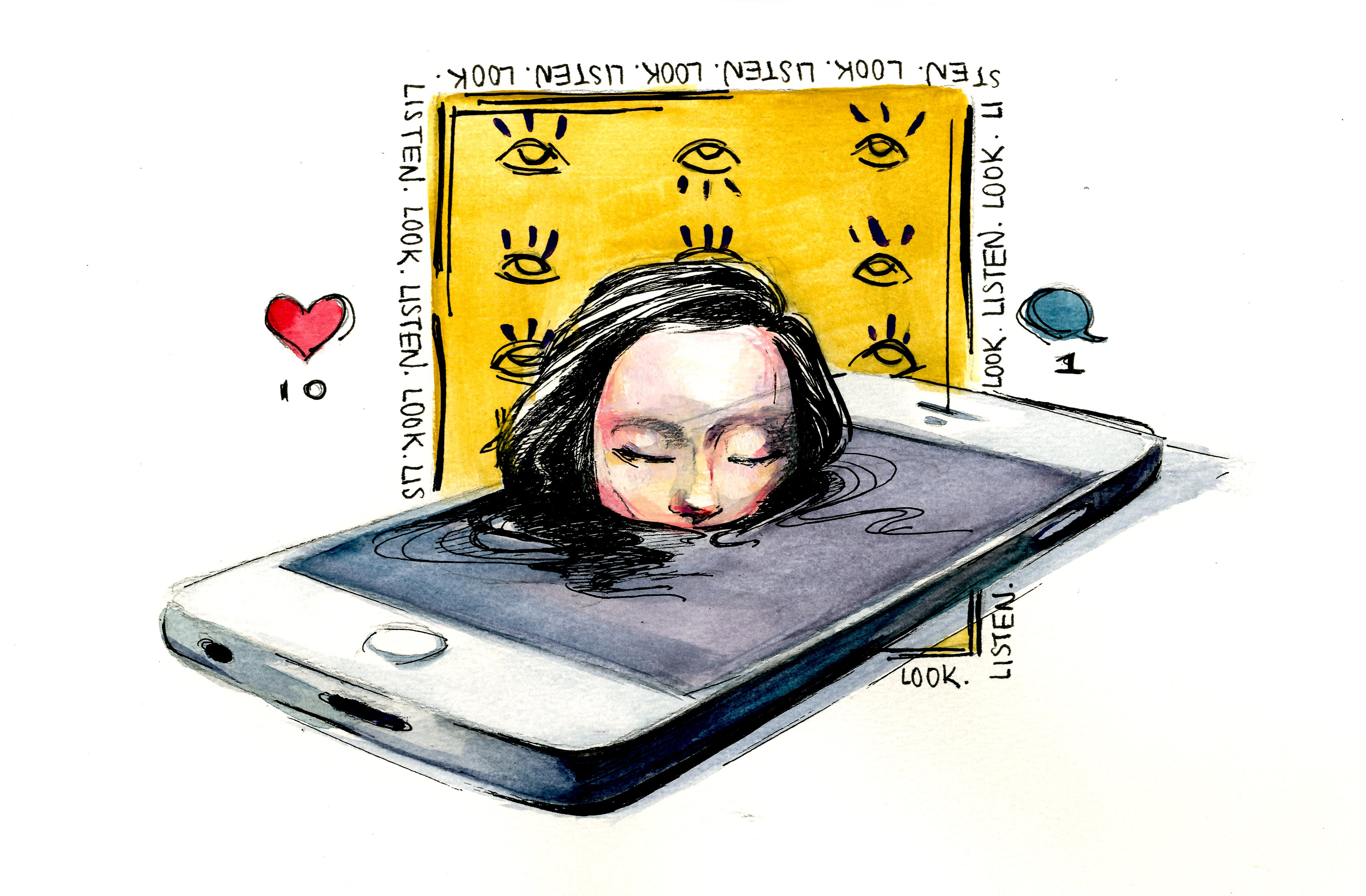

“Our public Instagrams are the real finstas,” a friend said to me as we walked to the dining hall. She was referring to the trend of finstagram, private “ fake Instagram” accounts whose confidentiality is supposed to allow for a more authentic social media presence than the curated assortment of happy photos we see on regular accounts. There are friendship finstas, confessional finstas, joke finstas and finstas dedicated entirely to pictures of cups (I have seen it). Accounts have a varied number of followers, but all aim to give a semi-private window into someone’s life. I had not spoken to my friend in person for a week or so, but her finsta ensured that I was up to speed on everything — who she missed at home, which class she fell asleep in on Tuesday, the small fight she had with her girlfriend.

In the nonstop onslaught of work, meetings, rehearsals and classes that comprise Yale, finstagram has a unique appeal here. At the beginning of the semester, I decided to hop on the bandwagon and created a private account. My finsta feed is almost a collective consciousness. A friend from home said it best when she commented, “I feel like this is a new plane of existence for our friendship to be on.” In a way, it is another plane of existence, one within a carefully curated group of followers, where friends from home can meet friends from Yale in the comments section.

An elaborate social code surrounds this plane of existence, and the cardinal rule is to not follow a finsta unless that finsta requests your public account first. Then you may request the finsta back, and if you have a finsta of your own, you can request their finsta with your finsta, thereby giving them permission to follow your finsta. Do you follow?

Alex initially created a finsta with the intention of posting emotional updates but quickly discovered that she did not feel comfortable being so open on the Internet. “[I]t feels weird talking about … emotions on an easily accessible Instagram account,” she told me. Over time her posts evolved into more factual, less emotionally charged updates about her life or “really weird, unattractive photos” that she thinks her friends will appreciate. Blake, on the other hand, has no problem whatsoever with broadcasting his innermost thoughts and feelings. “I go very stream of consciousness when I write these, because just being able to get the thoughts right out makes it much more consistent with how I’m actually thinking as opposed to if I’m trying to make it a well-phrased essay,” he said. “I’m just word-vomiting.” But here’s the catch: you don’t get to respond to Blake’s posts per his own rules. He prefers a passive audience, for his followers to bear witness to what he is going through without trying to advise or pass judgment. One of his recent posts explicitly tells people never to discuss his account with him.

Other than Blake, almost all Yale students interviewed said that they would characterize the tone of their captions as self-deprecating. “My rinsta — real Instagram — is upbeat, like, ‘Be jealous of me! Look how great I am! Don’t you want this lifestyle?’” Kate said. “Whereas my finsta is kind of more self-deprecating and laughing at myself.” Self-deprecation allows people to post incredibly honest and intimate details without the sting of vulnerability because they are self-aware, even capable of making light of their situation. Kate went on to say, “[I]t’s almost like I’m making fun of myself to take away the power of others to make fun of me.” But claiming that power can be harder than it seems. Kate said her posts are sometimes a “cry for help” and that it can be disheartening to receive only a single text regarding an emotional post on her finsta that garnered more than 30 likes.

Self-deprecation is also inherent to the Internet vernacular that characterizes finstagram captions. On finsta, it is not uncommon for “haha” and “lmao” to be more common than punctuation. Oftentimes they are coupled with an expression of emotion or struggle that is anything but funny. Even the decision to capitalize “lmao” or leave it lowercase can change the emotional nuance of a phrase, intentionally undermining or amplifying the weight of a statement.

Finstagram operates with a strange combination of authenticity and self-deprecation, which begs the question: Is it reducing our ability to talk spontaneously about our emotions or giving us a kind of fluency that is too new to have any value yet? As shown by the elaborate ritual of following someone’s finstagram, it is not a practice that lacks social or self-awareness.

“It always is easier to express your emotions when you write it down. And you don’t have to see … an immediate reaction on someone’s face or have someone … say words to you and react to what you say,” Alex said. In some cases, finstagram may undermine its own purpose of authentic, honest expression because it allows people to edit and control the expression. It is not so much about the feeling being expressed as the presentation of that feeling: a blunt, straightforward caption about being anxious about a midterm may be taken more seriously than a caption peppered by lol’s and shrugging emojis, yet the feeling underneath them all remains the same when it comes to finsta posts.

Kate confirmed that even when she’s putting all her cards down, she is still in control. “When you think of the phrase putting your cards down, you think of a randomly shuffled deck, but it’s like I’m the one in control of the deck. I’m the dealer and I’m the one putting down my cards … I can edit and re-edit the comment multiple times before I actually click post,” she said. Even supposedly confessional moments may be manipulated — part of the artifice of finsta is claiming to reveal your artifice, but in a controlled way.

In the world of social media, the thought experiment “if a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?” is effectively rendered irrelevant, because, whether or not anyone is there, the event will be documented and witnessed in some way. The better question may be “if a tree falls in a forest and posts about it on its finsta, did it even fall, or is it just trying to portray itself as lovably clumsy so people relate to it more?”

If the question regarding finsta is whether it is another manifestation of manipulative social media, a tool for expressing emotions, a replacement for human interaction or just a trend, the answer is yes to all of the above. It may be a sly continuation of self-branding in the quest for social capital, a cathartic shout into the void to be witnessed but not discussed or a way of catalyzing conversation in real life. But this is not just a new generation with an unprecedented need to share.

“I think finsta’s just another outlet for people to do things that they’ve been wanting and needing to do for always,” said Blake. “Before finsta there was BlogSpot, and before that there were physical journals and across all of this there is counseling. It’s not like ‘Whoa, look at all of these kids who suddenly have to talk about their feelings.’ No, kids always had to talk about their feelings. It’s just visible in a different way.”

And perhaps it is the new visibility for less than perfect moments that makes finstagram revolutionary. People do not display intimate details of their lives because they have fallen prey to millennials’ alleged “special snowflake” mentality — that their struggles are so unique that these moments warrant social media presence. Rather, witnessing one’s peers articulating what they are going through normalizes one’s own struggles and breeds camaraderie. It serves as a reminder that you are not the only one who has been dumped or failed a midterm or is really obsessed with cups. Like most social media platforms, it will likely lose popularity and eventually fade from popular culture, but the needs it addresses will not.

“Finsta is just another way people are dealing with feelings,” said Blake, “which is always a thing because we are human beings.”

*All names have been changed so that finsta identities are not revealed.