David Hurtado

New Haven is among four Connecticut cities struggling to battle a disproportionate percentage of the state’s poverty, public education and crime, according to a Sept. 26 report from the state’s leading municipal lobbying group.

In many Connecticut urban hubs — particularly New Haven, Waterbury, Bridgeport and Hartford — local legislators are finding that revenue is insufficient for funding services that cater to their most vulnerable citizens. Published by the Connecticut Conference of Municipalities, a nonpartisan organization that represents 162 Connecticut communities, the report also warns that property taxes in these cities will rise even further if action is not taken to develop other sources of municipal funding.

“[New Haven] bears a very high burden for providing services to a lot of needy residents and property tax rates are very high in the city because of all the stress of providing all the services, which cost money,” CCM Director of Communications Kevin Maloney said to the News. “[Local legislators] need support from the state and federal government in order to maintain the vibrancy of New Haven.”

He added that this additional funding could potentially come from the state sharing a portion of the sales tax with local government.

The CCM released the bulletin as a continuation of its campaign to raise awareness of certain issues during the races for state and federal office this fall.

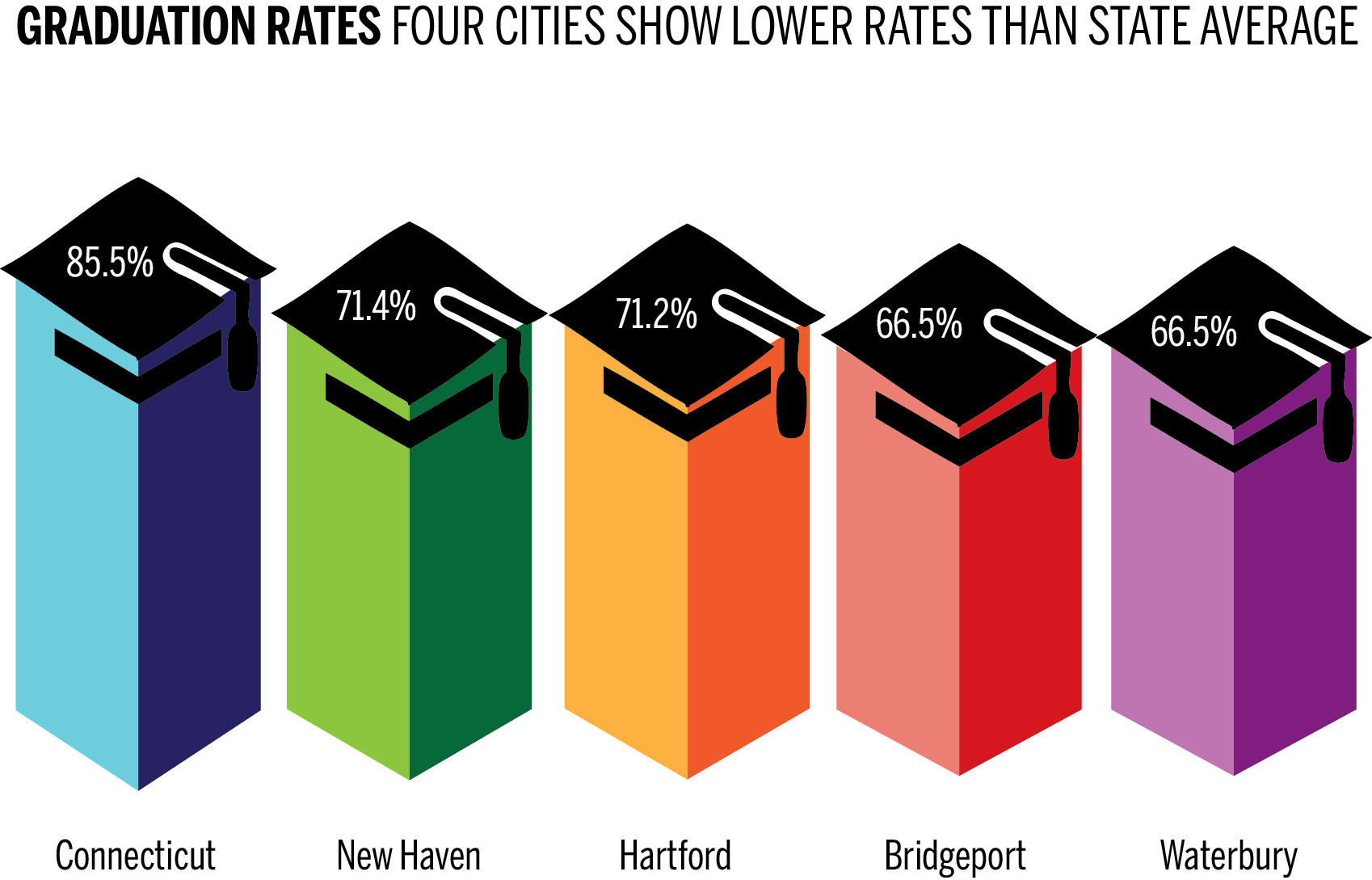

According to the report, the average rate of poverty in the four cited cities is almost twice as high as Connecticut’s average of 8.6 percent; in New Haven, the rate is even greater, at 21.1 percent. Schools in the four cities teach nearly 15 percent of the state’s public school students but have an average graduation rate of about 69 percent, which is significantly lower than the state’s average of 85.5 percent. Approximately 13 percent of students in the four cities’ schools are English language learners, whereas that number for all of Connecticut is 5.2 percent. Additionally, crime rates in New Haven, Waterbury and Hartford are also more than double the state average.

“Just on the education side alone, the CCM report illustrates accurately the disproportionate funding between the urban impoverished communities and the affluent suburban communities,” said Waterbury Mayor Neil O’Leary. “And it’s to the detriment of the city and the quality of life in the city because of the high [property tax] rate for our tax payers.”

O’Leary, a director of the CCM, said the issue of underfunded education in urban centers is particularly concerning. According to O’Leary, evaluations for city funding from the state have not been renewed recently, despite changing enrollment numbers across municipalities. Thus, schools with an increasing number of students receive the same amount of money than they did when fewer students were enrolled, and vice versa.

He pointed out that schools in Waterbury, for example, have seen an increase in about 750 total students over the past five years, while suburban schools have instead seen decreases in enrollment ranging from 17 to 22 percent. He called the disparity a damage to the civil right to an equal public education.

In a Sept. 7 court ruling concerning equity in state funding of schools in Connecticut cities, Judge Thomas Moukawsher of State Superior Court in Hartford said, in accordance to many of the CCM’s claims, that Connecticut has helped wealthy schools thrive while leaving poor schools to struggle. He added in the ruling that “change must come,” and ordered the state to come up with new methods for determining state education funding.

“I think quite clearly the judge is saying, ‘Hey, Connecticut, get this right, and get it right quickly,’” Gov. Dannel Malloy said to reporters after the ruling. “And quite frankly, I think we should get it right quickly.”

The issue spans to include services besides education. Mayor Toni Harp, also a CCM director, told the News that disproportionate state funding is further exacerbated by the high concentration of poverty in Connecticut cities. She added that expenses are high to provide essential social services, while the ability to raise revenue is compromised.

Both Harp and O’Leary mentioned the large presence of tax-exempt institutions in their cities as factors contributing to the “disproportionate burden” on urban centers. Cities provide a stage for hospitals, higher education and religious institutions, Harp said, but cities are at a disadvantage as they are restricted to property tax for primary funding.

O’Leary acknowledged that the state is working within its own constraints, citing the effort to recover after the 2008 recession. Yet the message of local leaders remains consistent.

“It’s in the best interests of Connecticut as a whole to address this matter, because the cities meet a critical need as centers of commerce, education, culture and so many services, and they cannot be allowed to fail,” Harp said.