Even before she came to the U.S., my mom knew about Norman Rockwell. Observing a newly opened Rockwell exhibit somewhere in the heart of Seoul, she peered into what she thought was “America”: clean-cut neighbors within framed rectangles who shoved large birds into the oven together and sat atop pool chairs sloppily licking ice-cream cones. The image encapsulated her vision of America, in her mind a final destination for naive dreamers who uprooted their entire lives for cotton candy illusions. When the time came, she packed the only suitcase she thought she would need while balancing a screaming child on her hip. She said to herself, with almost mechanical repetition, “Just three years. Just three years.”

A small section of my bedroom wall was once covered with mini Rockwell posters. Sometimes, before going to bed, I would look at one of the prints, with its swollen bubblegum-faced characters, and feel a sense of relief, comforted by how normal and sweet their lives were. The posters were lined up side-by-side, the paper crinkling at the corners and slightly torn, revealing the multiple layers of white card-stock under them. Complemented by the view of the quaint, earth-toned suburban houses from my bedroom window, the characters seemed like they belonged.

Last fall, I became obsessed with the idea that suburban houses were personal utopias. My sociology professor, the head of a residential college, squeezed 16 of us into her living room at 9 a.m., twice a week. Shoulder-to-shoulder, we arranged ourselves around a too-low coffee table while her cat, Nini, traced the edges of the sofas with her paws. John C. Calhoun’s portrait looked down on us as we compared suburbia to the Jeffersonian ideal of property holding — the satisfaction and privilege of having a stake in something and not having to share it with anyone else. We didn’t talk much about the people who lived within these private, personal utopias or the ways in which they interacted with one another. Between slurps of coffee, we silently agreed that the neighborhoods, despite their perfect facades, had walls and fences between each house for a reason.

Sometime before our three years in the U.S. turned unwillingly into twenty, my family and I had constructed our own “American Dream Lite.” Always set against the backdrop of the suburban landscape, it consisted of chlorinated water and watermelon, the smell of barbecue and overly enthusiastic hellos from across the street. We pulled on our bathing suits and slathered on too much sunscreen with our Rockwellian, ice-cream licking, bird roasting, golden-haired neighbors, splashing around in kiddie pools, nostalgic for an unrealized dream.

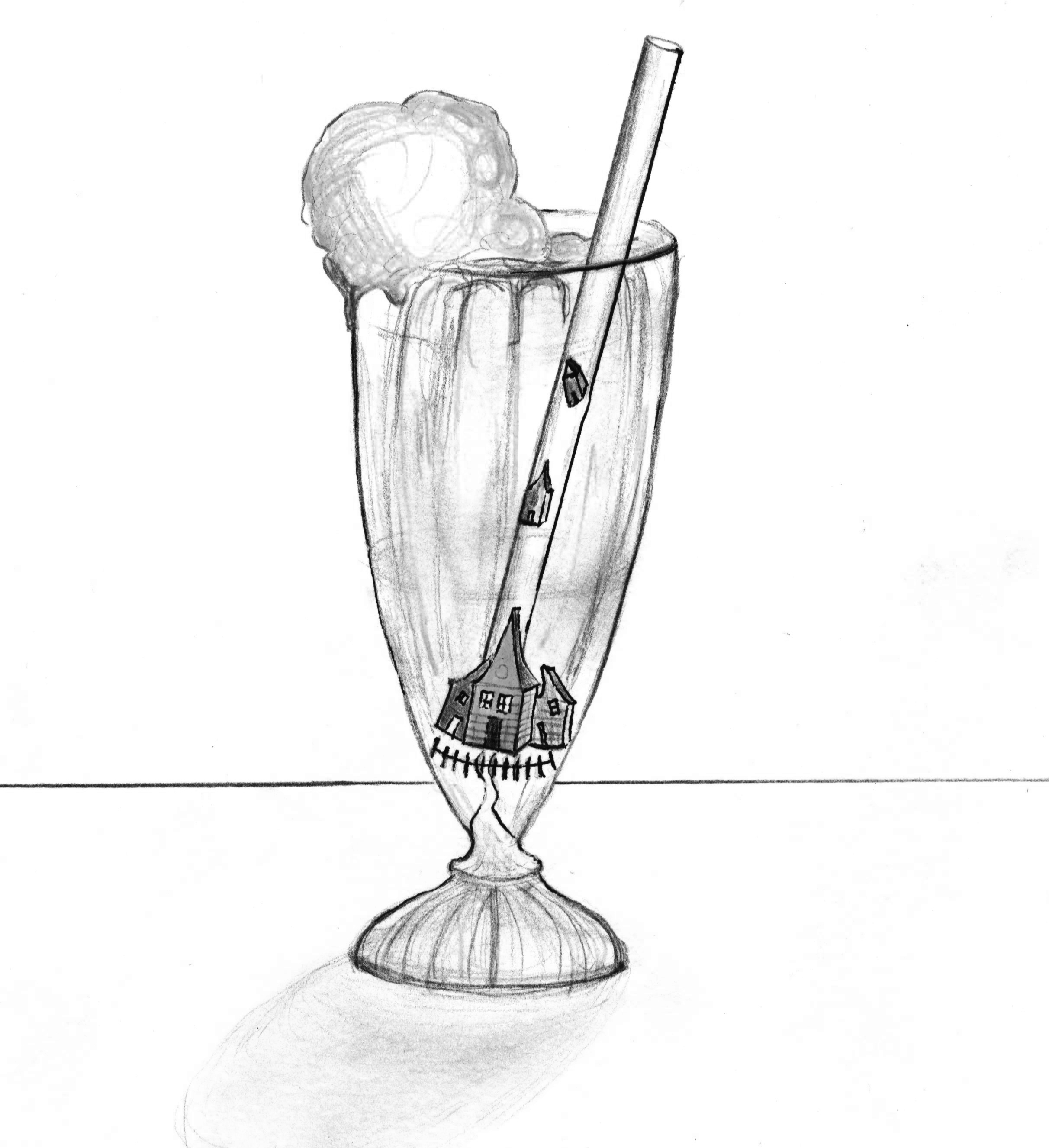

On Friday afternoons, I made the three minute walk to Sammie’s house because her mom headed the local Girl Scouts chapter. I joined and quit the organization that summer after I walked into a room of margarita-drinking neighbors mimicking my mother’s accent, cackling with the relief of knowing that it was not yet their turn to be picked apart. I held onto the moment like a treasure and ran all the way home to my mom, whizzing by street-side cacti and powered by the sound of a thousand barking dogs behind their gates. After I was done dramatically gesticulating with my seven-year-old hands, trying to recreate it all, she told me to stop going to the meetings. Bit-by-bit, our desires for a communal, suburban utopia were sucked dry through a twisted, red, white and blue striped straw.

My next-door-neighbors were white. Unsurprisingly, they were one of the only white families on the block, since around 81 percent of my city identifies as Hispanic. We tried not to get in each other’s way, but with five kids next door, it always proved more difficult than expected. Jack, who went to school with me, swung on his swing set everyday while facing my backyard. Every time his Sketchers left the ground and the magnified orbs behind his glasses connected with mine, I would hear a shaky hello. His Michelin legs swung so vigorously, his cheeks pumping so much air through them, that I would sometimes wait for him closer to the stone wall between our houses so he wouldn’t have to push himself so high. His mom thought I was bullying him after I convinced my friends to go the wall with me one day after we heard a series of timid, whispered hellos. She must have been surprised by how much he was talking, figuring that it was a call for help. For a few months after that, a murky-looking tarp appeared, extending the stone wall by a meter and obscuring our greetings and vision. Once the wind eventually took care of the tarp, Jack’s little sister climbed the wall and swam in our pool. My mom found her plump form drifting up and down the sides of the pool like a baby otter. Scared to death that she might have drowned, she took her back next door and got yelled at by Mrs. Murray for abducting the little sea mammal.

My parents called the realtor at least once every year for a decade. They were convinced that we just hadn’t found the right “community” yet. Somewhere out there, networks of sticky-fingered apple pie lovers were waiting with open arms and housewarming parties. We never moved but renovated and expanded, constantly revising and trying to find utopia by searching inward. My parents, my pocket-dictionary mom especially, needed to assert their individuality somehow. We looked different; we were treated differently; and soon our house had a deep green door and was covered in a slightly sad shade of blue. It sighed, “Look at me. I dare you.” After that first renovation, the next eight years were speckled with little revolutions that involved teams of Mexican workers and blazing summer sidewalks.

This summer, we didn’t renovate. Instead, Cole Truman, the grandson of a successful local businessman, died in a neighborhood that was five minutes away from mine. They found him sprawled face-down, lying on the driveway of an upper middle-class stranger’s house with a bullet wedged into his stomach. In the aftermath of the murder, a resident of the neighborhood told the media he was shocked by the shooting because it had happened in an area “reminiscent of a Norman Rockwell painting.”

I was surprised that other people in the community wanted it too, the Rockwell ideal, or, in this case, had convinced themselves they had found it. I thought about what this obsession with Rockwell meant in the larger scope of things and the danger of calling an 81 percent Hispanic city a white ideal. After all, most of my neighbors and I were actors performing in a white power structure our suburban grids forced us to use as a backdrop. I wondered if all of American suburbia consisted of isolated homes without any real sense of community or if it was a problem unique to this city because we were trying to be white without a dominant white presence. Or maybe it really was just my family feeling left out.

My parents’ most recent renovation has been the huge beige wall around the patio that obscures them from the other neighbors. While my parents sit there with a pot of chamomile tea, they hear cameras clicking and people talking about the gate while on morning jogs. During the next few weeks after the patio was finished, at least six houses in my own neighborhood, and a few others in tangential suburbs, started creating their own walled-off spaces — some wide and clunky, others only large enough for a couple of chairs. The construction of these personal enclaves revealed to me, for the first time, the individuality of my neighbors and the widespread loneliness of living within a community built on sameness.

Sometimes when I see my parents sitting in their bathrobes on the yellow reclining chairs on our patio, I see that the newly erected walls obscure the other houses on all four sides. In their places, blue floods the surroundings all except for the purple, stone mountains that lay gently on top of the patio walls in full view. Looking at the duo, I wonder if faces that are so content could be produced by anything other than finally finding their utopia. When I drive through my neighborhood now, I always imagine each family sitting in their own constructed enclaves, closer and more similar to one another than they have ever been or expected to be, but too obscured to realize it. I’m sure that they, too, act as if the mountains and scenery are completely their own.