Every weekend, scores of Yale students stumble through the streets, intoxicated with what scientists have deemed one of the world’s most harmful drugs: alcohol. Most of them return home with little worse than a hangover the next day. However, we’ve all known (or been) someone who has had too much to drink: to put it plainly, overdosed on alcohol. And thanks to Yale’s new alcohol amnesty policy, implemented last year, we know that if a friend passes out or starts vomiting uncontrollably as a result of alcohol poisoning, we can call for help without fear of disciplinary penalties.

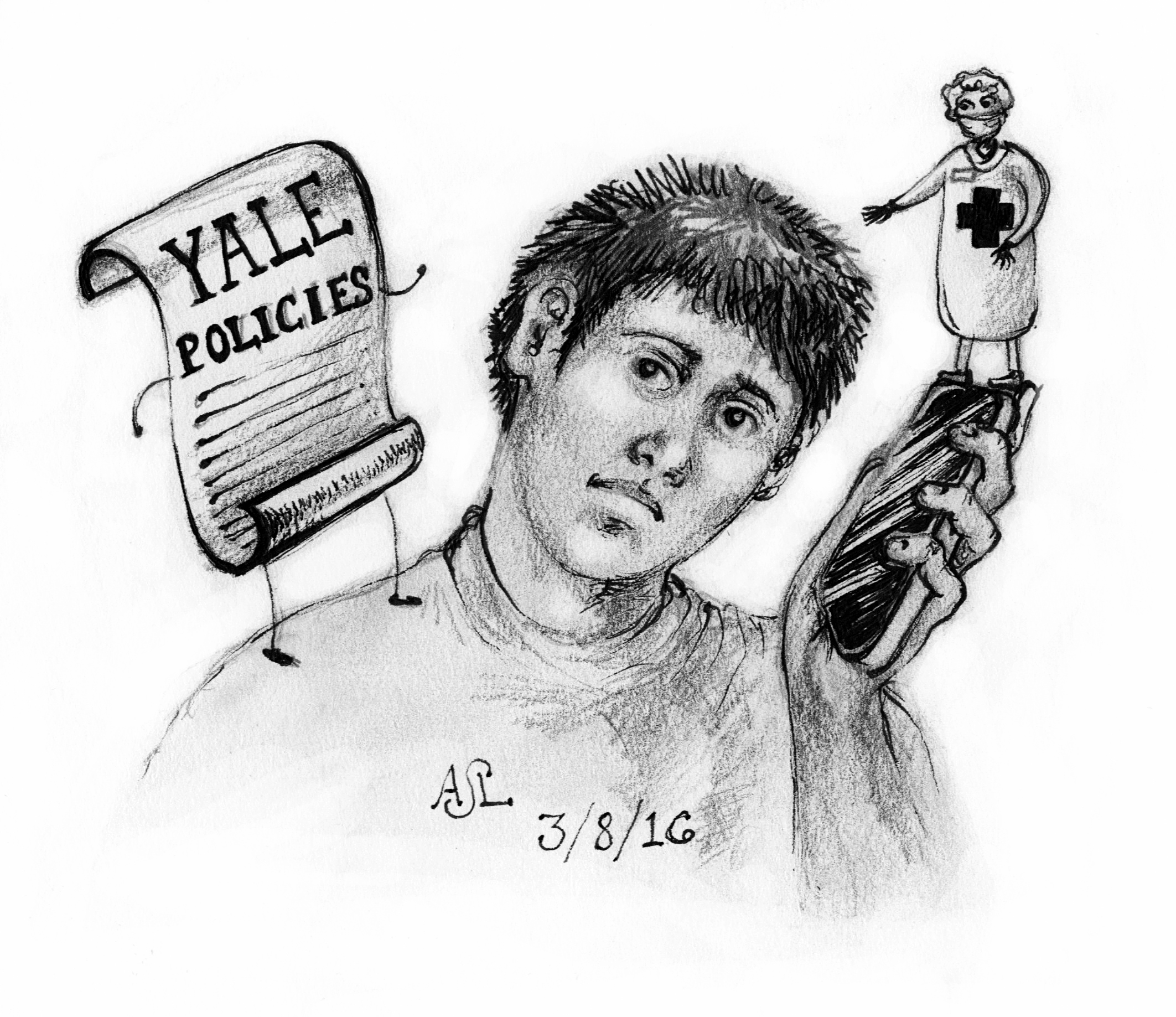

But what happens if you or a friend is having a serious medical problem with a drug other than alcohol? As of now, Yale provides no protection for students in this situation. Someone who calls for help for these types of overdoses risks penalties that could be as extreme as expulsion and referral for criminal prosecution.

This situation is likely common to hundreds of students on campus. Out of 1,844 respondents to the Yale College Council spring survey, 83 had “hesitated to call for help for someone experiencing an adverse reaction to drugs other than alcohol because they were worried that they might face disciplinary consequences.” Extrapolating this data to all 5,453 undergraduates, over 245 current students share this experience. Even if they ultimately do call, just a few seconds of hesitation can be critical. That’s 245 students whose hesitation to seek medical treatment for a friend could lead to serious health consequences, even death.

Some might argue that a drug amnesty policy encourages drug use, but this policy would only apply in emergency situations. And the fact is that students will use drugs anyway. In 2014, the News found that 44 percent of students violate Yale’s drug policy; 42.2 percent of these students referred to marijuana, and the other 67.8 percent had used drugs like prescription stimulants, cocaine, MDMA and LSD. There is no evidence that such a policy would increase student drug use. What it would increase, however, is the amount of students receiving treatment for addiction. For example, since Cornell implemented a similar alcohol policy, the number of students receiving treatment for alcohol misuse has doubled.

If thousands of students are violating Yale’s drug policy, this means that thousands of students are exposed to a clandestine, unregulated market where the substances sold and consumed might not be what they seem. Last spring, 12 students at Wesleyan’s Spring Fling were hospitalized after consuming a tainted batch of MDMA — a substance that is notoriously impure and often sold under false claims. Who’s to say it couldn’t happen here?

Yale itself is not immune to tragedy. Just before most of us arrived on campus, Andre Narcisse ’12 died in a poly-drug overdose. And, of course, there are the many untold stories of students suffering from drug problems who haven’t died or been on Yale News, problems known only to those close to them, or perhaps known to no one but themselves.

Five other Ivy League schools have drug amnesty policies. In fact, even the state of Connecticut has the equivalent, known as a Good Samaritan law. It’s time for Yale to catch up and extend its medicial emergency policy to drugs other than alcohol. It’s a problem we’re uncomfortable talking about, but it isn’t going away. And by taking a more public-health-oriented approach, Yale can get students in medical crises the help they need instead of the punishments they don’t.

Annelisa Leinbach is a senior in Calhoun College. She was the Illustrations Editor of the Managing Board of 2015. Contact her at annelisa.leinbach@yale.edu .