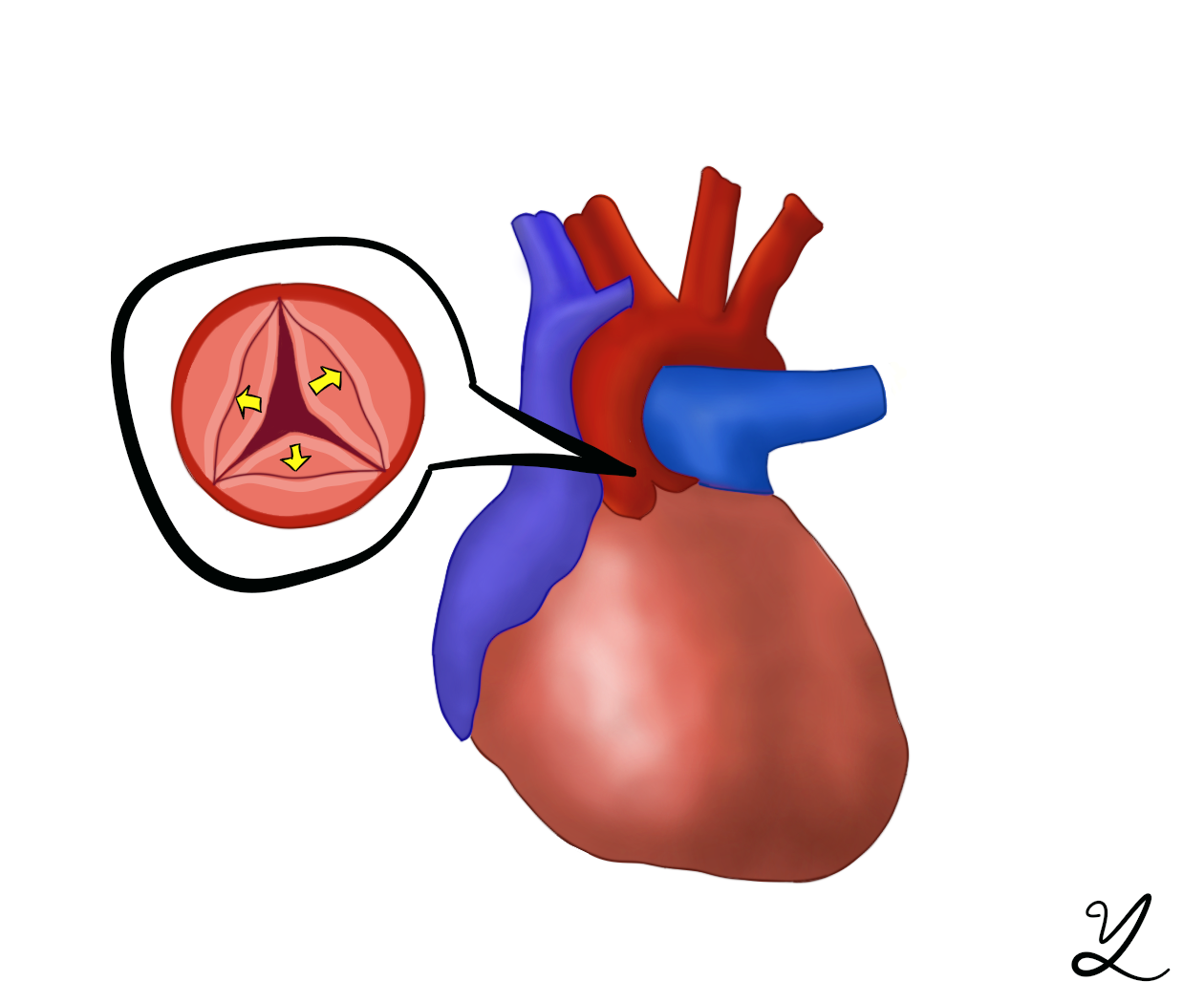

New research from Yale points to more effective treatments for supravalvular aortic stenosis, a disease in which dangerous narrowing of the aortic valve opening to the aortic artery increases patients’ risk of cardiovascular disease.

In order to learn more about factors that harden or constrict the aorta, one of the body’s biggest arteries, researchers studied mice that had been genetically modified to lack a copy of a key gene that codes for elastin, which helps keep arteries supple and functioning optimally. By comparing tissue samples from these mice with tissue samples from humans with supravalvular aortic stenosis, researchers were able to hone in on a specific protein, called integrin beta3, which appeared in higher levels in diseased human subjects and genetically modified mice. Scientists treated mice with an integrin beta3 inhibitor, and found that the narrowing of the aorta was less pronounced in the treatment group. This finding suggests that developing equivalent drugs for humans could help control levels of integrin beta3 and thereby reduce the impact of supravalvular aortic stenosis in humans.

“To the best of our knowledge, no one has ever shown that interventions for elastin-null mice could successfully increase their lifespans,” said Daniel Greif, study co-author and professor at the Yale School of Medicine. He noted that the researchers were interested in the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying the disease, and using modified mice allowed them to isolate key factors of interest including the role of integrin beta3 and reduced elastin.

In a Feb. 8 news release, Ashish Misra, the first author of the study and a postdoctoral fellow at the Greif Lab, noted that longer lifespans of treated mice had never been observed in previous cardiovascular studies.

Greif likened the vascular system to a hose: The more rigid and narrow it is, the harder it becomes to pump fluids through. Supravalvular aortic stenosis hardens the opening to the aorta and narrows the artery itself in a similar way, putting a strain on the heart or “pump,” he added.

Elastin is a critical part of maintaining flexible arteries, so the modified mice, which lacked copies of the elastin gene, were at very high risk of developing the mouse equivalent of supravalvular aortic stenosis.

Grief noted that their research points to a way to prevent aortic stenosis from worsening in diseased patients, and that their work could even eventually result in reversing some of the damage in patients’ aortic stenosis.

Risk factors for aortic problems include smoking, being male, high cholesterol and high blood pressure.