Last semester, we rallied for change. We cried, we marched, we petitioned and we fought the status quo. We denounced all aspects of categorization and labeling. We were united in the desire to uphold that oft-quoted aphorism: “Don’t judge a book by its cover.”

This week, however, we celebrate the creation of exclusive social groups — groups formed through superficial 15-minute conversations, through opinions on body type and body shape, through first impressions that are fake and unreliable in equal measure, through the judgment of just about every book by its respective cover.

But I’m sure you’re already familiar with rush.

With sorority rush having just concluded and fraternity rushes (the “clean” ones, at least) due to finish up over the coming weeks, Greek life at Yale will receive its latest influx of those well-versed in the art of “coming off well.” But for every “angel” and every “brother” celebrating with their new pledge class, there’s a student at home on bid night, guilty of nothing except an inability to pigeonhole himself or herself into a “srat” or “frat” stereotype.

How jarring that after working so hard to devalue stereotyping, we place so much stock in a system based in superficiality and first impressions.

I am a member of a fraternity on campus, and as a sophomore, have now experienced both sides of the rush process. To cast it in an entirely negative light would do a great disservice to both its intentions and its outcomes. Rush, both last year and this year, allowed me to meet guys who I wouldn’t have known otherwise, several of whom I’ve been lucky enough to form lasting friendships with. Further, in my experience, there has been a general awareness of the shortcomings of rush and an effort to minimize the artificiality of the rush process.

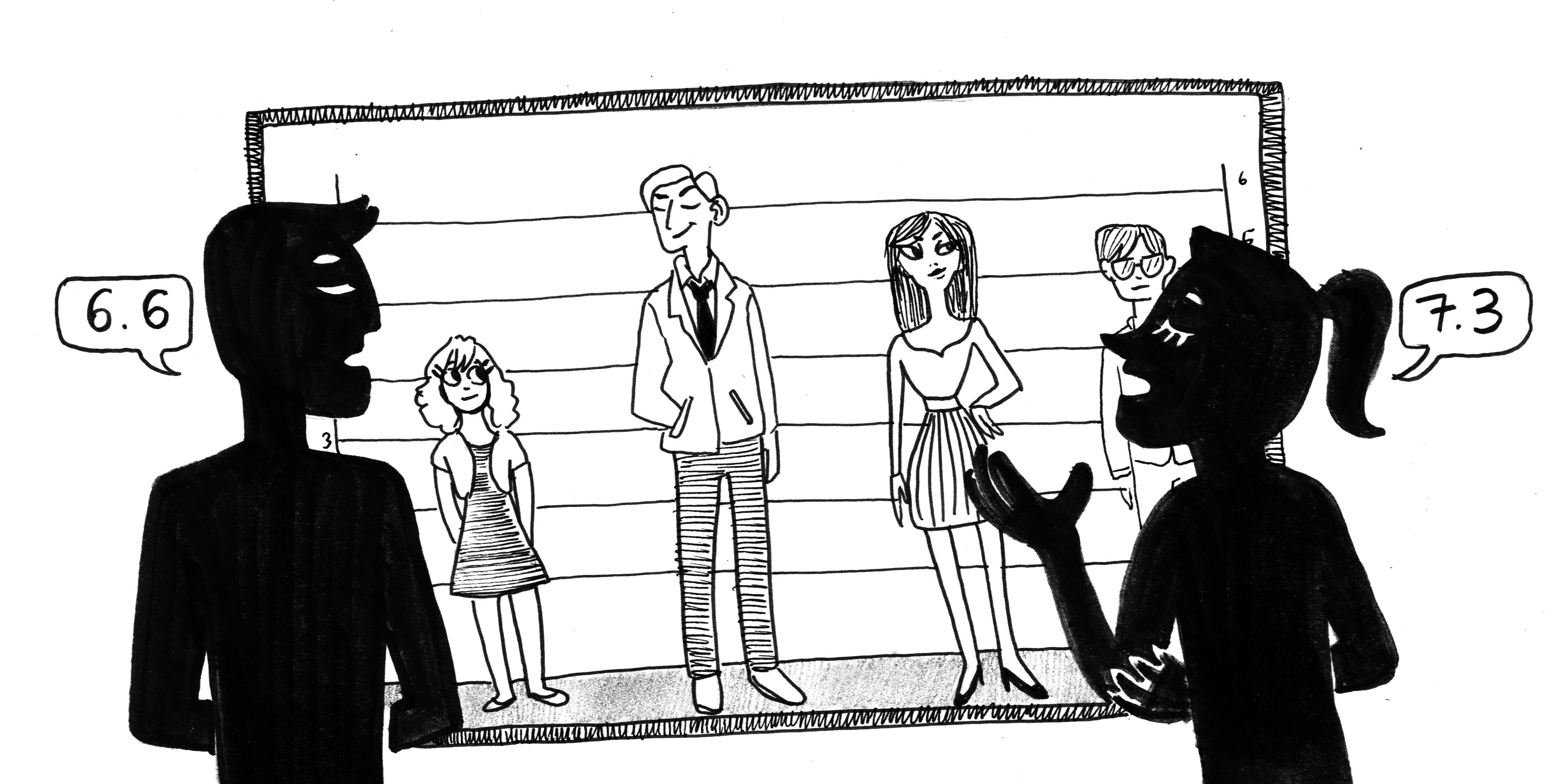

Yet it is impossible to completely iron out a system that is essentially devoted to establishing a social hierarchy. Groups across campus employ quantitative ratings to rank these students, a system that is grossly barbaric, and, more worryingly, deemed unavoidable. Is there a more dehumanizing way to evaluate a prospective brother/sister than reducing him or her to a number on a numerical scale? It exists because it is time efficient and, while excluding some, works well for many — one of the most common justifications for social stratification. How ironic that a selection process that can be so disempowering is the start of a brotherhood that promotes belongingness and self-improvement.

Stories disparaging the rush process abound, some humorous, some less so. From girls too self-conscious to eat the brownies laid out at their rush event, to guys feeling pressured to be spotted with a “hot chick” in front of their prospective brothers, to the hours spent preparing an outfit that strikes the perfect balance between “casual” and “semiformal,” we are all aware of the social biases that rush perpetuates.

And yet, Greek life at Yale has far less influence on campus than it does at other schools. Step off High Street, and you can enjoy a diverse social life completely independent of fraternities and sororities. Only 10 percent of the student body is involved in Greek life — for context, half of MIT students have gone Greek. Is it so bad that one small, completely optional segment of our campus tends to be overly superficial? Then again, is even one of these segments one too many?

I do not know the answers to these questions, and I often find myself trying to avoid them. As a member of Greek life, it is easier to come terms with the “fact” that the rush process has to be done. “It doesn’t make me feel good,” one sorority girl told me recently. “But there’s no alternative.”

At the end of it all, we are left with booze-filled celebrations of new pledge classes and triumphant profile picture changes featuring our new brothers or sisters, reaffirmations of a system that we only condone because it’s convenient.

Greek life has many positives. But in our desire to go Greek, we must be careful not to stereotype both others and ourselves based on boat shoes and hairdos. We must acknowledge and celebrate our individuality, and we must reflect on our roles in a process that often doesn’t even open the book.

Mrinal Kumar is a sophomore in Silliman College. Contact him at mrinal.kumar@yale.edu .