Connecticut’s loss of General Electric, a multinational corporation with gross revenue of $150 billion annually, points to the state’s chronic inability to grow its high-tech industry to full potential, critics have alleged.

GE, which has been based in the Fairfield suburbs for the past 42 years, announced last Wednesday that it will relocate its headquarters to Boston. In a press release, the company cited the city’s concentration of universities and Massachusetts’ public investments in research and development as reasons for the move. GE’s decision should not come as a surprise to local and state officials in Connecticut, New Haven Economic Development Administrator Matthew Nemerson SOM ’81 said. He explained that the state has failed numerous times in the past decade to create a business environment that rivals Seattle, Toronto and Boston — which will house GE’s new headquarters by the summer of 2018.

“[GE’s decision to relocate] is the crisis we need to implement all of the plans that have been put forward all of these years to be a modern knowledge-creating state,” Nemerson said.

A 2010 survey of tech CEOs in the state conducted by the Connecticut Technology Council — an association of over 2,000 tech companies — found that 73 percent of CEOs doubted staying in the state would be best for their businesses in the long run. They cited issues such as state officials not recognizing the industry’s needs and difficulty connecting with the state’s university talent.

The CTC presented the survey results in the Connecticut Competitiveness Agenda. In the report, the association recommended that the governor adopt initiatives, such as expanding Hartford’s Bradley International Airport and Tweed-New Haven Regional Airport to facilitate the growth of high-tech firms. The most important recommendation was to concentrate funding in New Haven and Stamford to create clusters of high-tech companies that could collaborate and compete, said Nemerson, who authored the report with other members of the CTC.

Malloy adopted the association’s agenda shortly after his first gubernatorial election in 2010, Nemerson said. But the plan’s call to create tech hubs in New Haven and Stamford could not withstand representatives jockeying for funding for their own districts, he added.

“[Malloy] had to put things through the General Assembly,” Nemerson said. “When you’re the governor of a small state that has many medium-sized cities, it is almost impossible to say that this city of 130,000 is more worthy than another city of 130,000.”

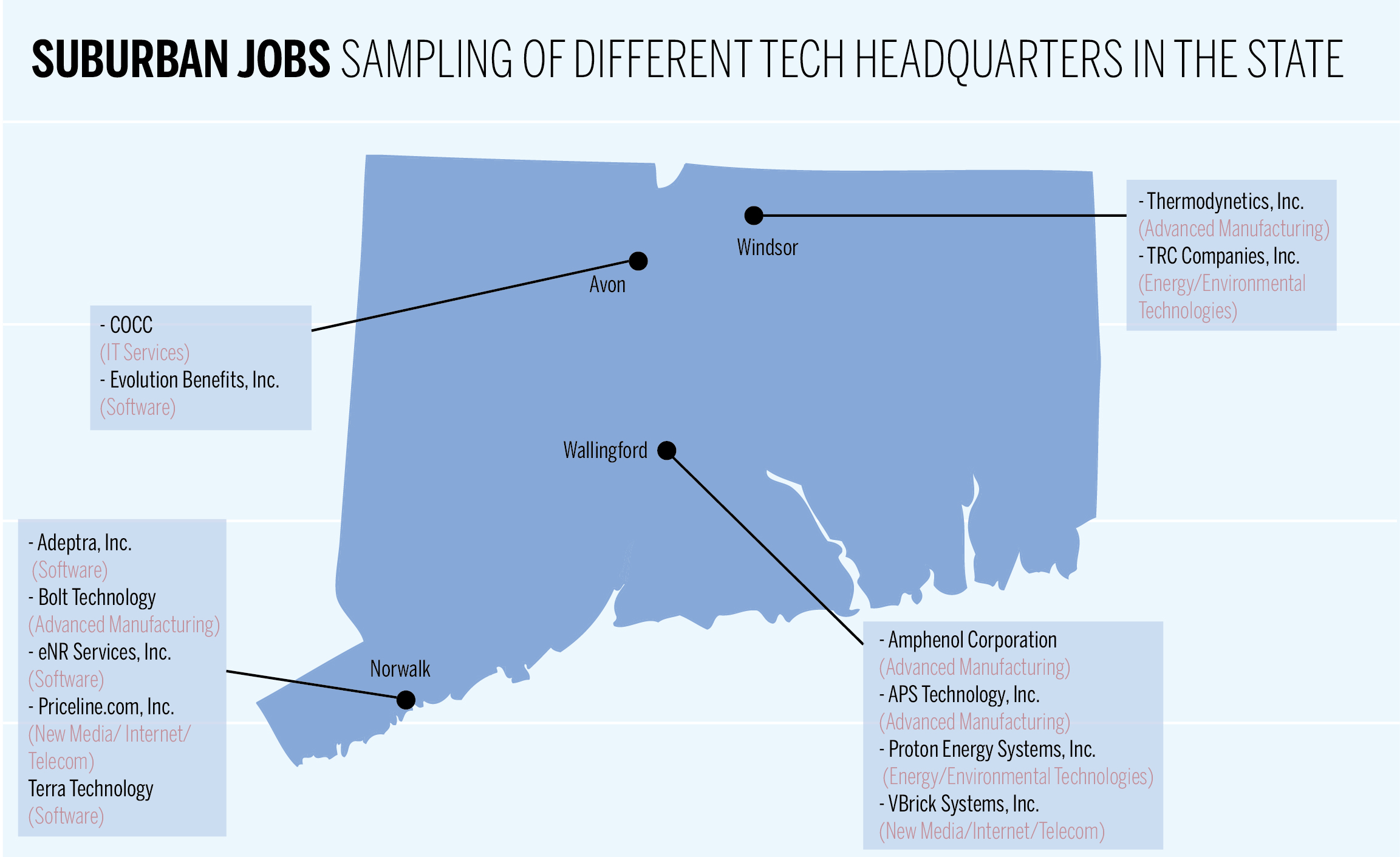

Despite the state’s hesitation to create hubs of high-tech jobs in select cities, data shows that doing so would meet the job demands of Connecticut’s recent college graduates. These professionals overwhelmingly choose to live in cities rather than suburbs, said Mark Abraham ’04, executive director of DataHaven, a New Haven-based nonprofit data analytics group.

University of Connecticut student Brian Tang said he wants to stay in his home state after graduation. But he said he does not see a future in Connecticut because almost all job prospects are located in the suburbs, which he cannot reach without a car.

Though Tang recognized state leaders have been advocating for companies to move to cities, he said the state should finally take action.

“Connecticut should focus on encouraging companies already in the state to move their operations to the center cities,” Tang said. He added, “Connecticut cities need to look more like Boston.”

GE’s search for new headquarters began publicly in June.