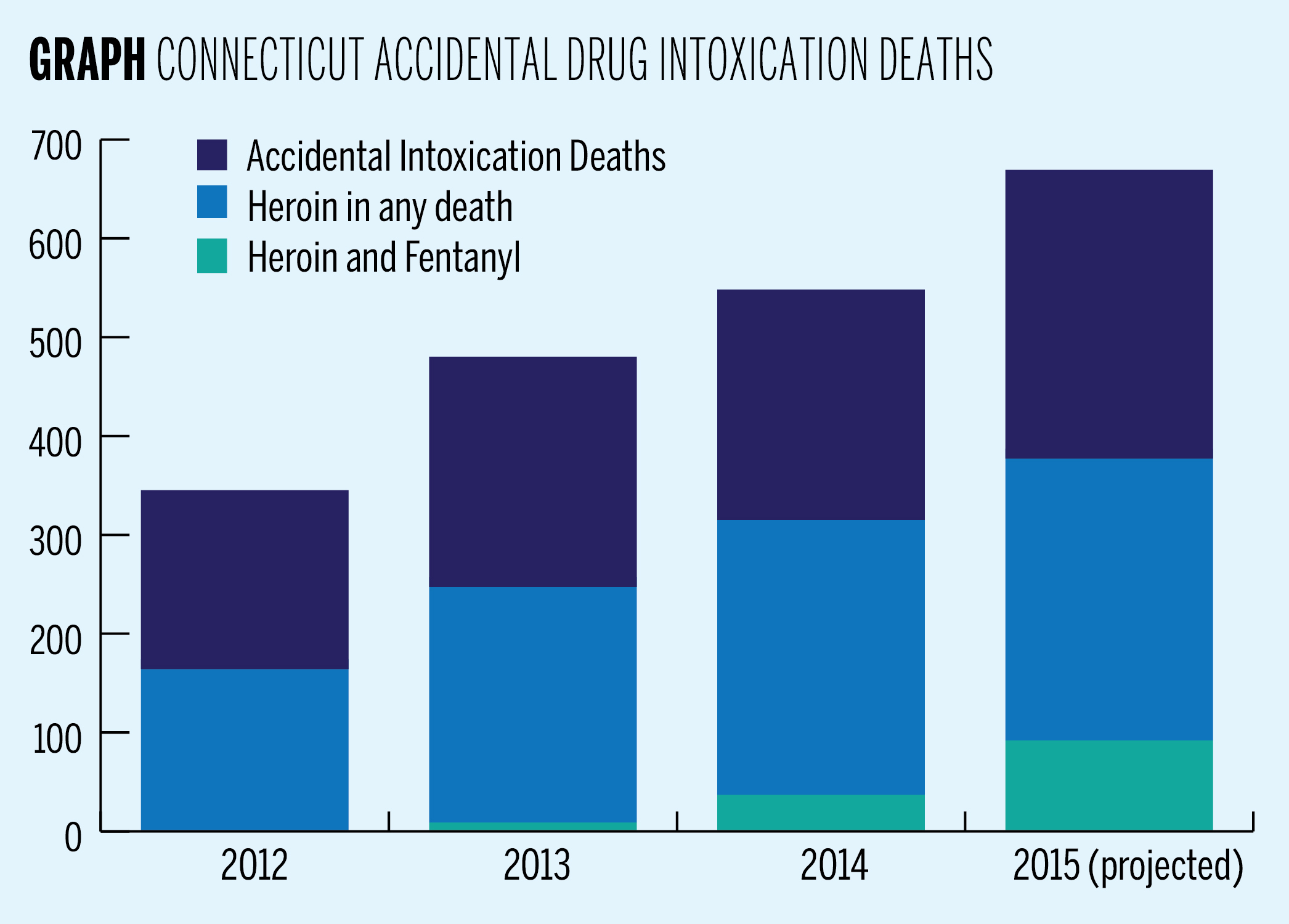

By the end of this month, the Connecticut Chief Medical Examiner’s Office expects that the number of accidental drug-induced intoxication deaths to rise by 22 percent from last year’s rate.

The number of deaths due to accidental drug overdose is expected to rise from 558 deaths last year to 679 by the end of this year, and the number of accidental heroin-related deaths is expected to increase from 325 last year to a projected 387. Between January and September this year, there were 290 heroin-related deaths in Connecticut, and deaths related to other pharmaceutical opioids are also on the rise. The state expects a 95 percent increase in accidental fentanyl-related deaths by the end of the year. The chief medical examiner and professors at the School of Public Health agree that the increase in heroin-related deaths in Connecticut is noteworthy. But different approaches to data collection raise questions about which substances pose the largest problem for Connecticut.

Connecticut’s Chief Medical Examiner James Gill said in the past few years heroin, not other pharmaceutical opioids such as oxycodone, has been the largest problem in the state. But Lauretta Grau — a clinical psychologist at the Yale School of Public Health who collected data on the subject — said the increase in heroin- and morphine-related deaths, as well as pharmaceutical opioid deaths, increased significantly between 2009 and 2014, indicating that drug-abuse problems extend beyond just heroin. And Yale pharmacology professor Robert Heimer GRD ’88 said though he would not describe the increasing number of drug-related deaths as an epidemic, there is a major problem with substance abuse in the United States, and opioids are just the most obvious example of an increase in self-medication in a substantial portion of the country.

“Don’t blame it all on heroin. Heroin is cheaper, but let’s not demonize just heroin, it’s a problem across the board. There’s more deaths that are involving pharmaceutical opioids and heroin,” Grau said. “I don’t think that going in and limiting the number of pharmaceutical opioids is the answer either. It’s complicated.”

Grau said different methodological approaches were applied to draw conclusions about whether opioids other than heroin are rising at a statistically significant rate. For example, Grau included both accidental deaths and deaths of undetermined causes in her data, whereas the Chief Medical Examiner’s Office only used information regarding accidental intoxication deaths.

The drug-related death that has seen the greatest expected percentage increase since last year is combined use of fentanyl and heroin. Fentanyl is a narcotic pain reliever that can be administered transdermally through a patch or an injection, orally or nasally.

Last year, toxicology reports detected heroin and fentanyl together in 37 deaths. By September of this year there were already 69 accidental fentanyl and heroin related deaths, and the Chief Medical Examiner’s Office predicts that the number will rise to 92 by the end of the year. These numbers are included in the count of both heroin-related deaths and fentanyl-related deaths.

Fentanyl-related deaths generally are expected to increase from 75 last year to 146 by the end of the year, according to data from the Chief Medical Examiner’s Office. Between January and September this year there were 110 fentanyl-related deaths.

“The fentanyl that we are seeing is from illicit fentanyl made in clandestine labs. It is sometimes mixed with heroin but it also can be purchased separately,” Gill said. “As there is no FDA on the street, people addicted to drugs have no guarantees about the dose, quality or composition of drugs that are bought on the street.”

Heimer explained that sometimes heroin and fentanyl are cut together to increase the rush that the user experiences. He said longtime heroin users often complain that the quality of their heroin is decreasing, when in reality this perception is due to decreased sensitivity to the substance.

Including heroin, the reach of illicit drugs is spreading.

“[Illegal opioids are] in all but 17 of the 169 towns in Connecticut. Between 2009 and 2014 all but 17 have experienced at least one overdose of an illegal opioid,” Grau said. “It’s spreading. There are very few communities aren’t affected by it.”

Heimer said interpreting numbers around illegal opioid-related deaths has to be done very carefully because many factors could contribute to the increase. He explained that one potential contributor to the spread of drug use is the sale of prescription medication to suburbanites by people who then buy heroin at a lower price.

“It’s a self-arranged substitution therapy,” Heimer said.

Heimer said another contributing factor is the increased availability of opioids. He said doctors feel compelled to help patients with symptoms of chronic pain. Because medication is cheaper than physical therapy, doctors have begun to rely more heavily on prescription drugs.

All three medical experts agreed that increasing understanding of drug addiction as a disease and destigmatizing it is paramount to countering these increases.

“Just like any disease, it affects all social strata and areas of our state. It took decades for medicine and society to recognize that chronic alcoholism is a disease. So is drug abuse,” Gill said in an email to the News.

Grau said there needs to be a more coordinated and concerted effort to not just address substance-abuse problems, but also to acknowledge that often those suffering from substance-abuse addiction are also struggle with housing, insurance and other issues that extend beyond simply obtaining treatment.

The data from the Connecticut Chief Medical Examiner’s Office was updated Nov. 17.