For exclusive audio content by Sarah DiMagno that accompanies this story, click here.

With 836 names listed on 33 varsity rosters, athletes make up just under 15 percent of the Yale student body. Yet even though they represent such a sizable portion of Yale’s population, these students often find themselves greatly mischaracterized.

Yale athletics — like Ivy League athletics in general — are anachronistic in the world of college sports, a world in which Big 12 football head coaches earn $5 million a year and Pac-12 student-athletes seek payment for the use of their likenesses. As any Yale student-athlete can confirm, the experiences of deified SEC football players or Big Ten basketball players are a far cry from those of the Ivy League athlete.

Being a student-athlete at Yale, the athletes themselves say, means balancing classes with a time commitment equivalent to a full-time job. But every athlete interviewed for this article made at least some mention of a perception among the rest of the student body that they were somehow undeserving of their spots here.

Indeed, in a News survey conducted for this article — responded to by 44 percent of Yale’s entire varsity student-athlete population — 33 percent of all respondents reported that they felt athletes were either not respected or actively disrespected by fellow students.

Last April, a close friend of mine on one of Yale’s varsity teams turned to me as we sat talking on Cross Campus one afternoon.

“For the first time in my life,” she admitted, “I feel like a dumb jock.”

—

Each year, approximately 11 percent of the incoming freshman class is made up of recruited athletes, with the remaining 4 percent considered to be walk-ons.

Per Ivy League rules, recruits are offered neither guaranteed admission to Yale nor scholarships. Coaches may offer conditional offers of support, pending a holistic review by the admissions office, but no money. As a result, members of the Ivy League are at a significant relative disadvantage to other Division I schools that can offer money to recruited athletes.

Despite that disadvantage, though, 59 percent of respondents to the News survey said they turned down scholarship offers from other Division I schools to attend Yale.

“On all of the rosters for each team, in the player biographies, it says ‘Why Yale?’” says Jessica Smith, who wished to remain anonymous due to the small size of her team. “I’ve never read one that says I came here for the sport. It says I came here for the people, I came here for the name, I came here for the institution and the learning that takes place here.”

When student-athletes choose to matriculate at Yale, they are most likely thinking beyond their careers as collegiate athletes.

Football head coach Tony Reno points out that Yale offers something different from other schools: a chance to compete at a Division I level as well as “the best education in the world.”

“You set yourself up for the next 60 years of your life when you come out of Yale,” Reno says. “At some of these other schools, it’s a short-term solution. You play for four years, maybe five years, and after that the degree isn’t quite what Yale’s is.”

With a few notable exceptions, such as crew, sailing, men’s ice hockey and men’s lacrosse, Yale teams are not competitive on a national level. A few recently graduated Bulldogs have found success in rowing, fencing and football, but for every NFL player like Tyler Varga ’15 or two-time Olympic fencer Sada Jacobson ’06, there are dozens of student-athletes whose athletic careers end at graduation.

—

Despite their lack of professional sports aspirations, though, most Bulldogs train the same number of hours as high-powered Division I programs.

“I think at any level of football in college, it’s going to take the same amount of time commitment,” says Bo Hines ’18, a wide receiver on the football team. “I would just say that the emphasis on academics is a lot greater here.”

Drawn to Yale’s academic opportunities, Hines recently transferred from a top-tier Football Bowl Subdivision program at North Carolina State. Hines says the intellectual atmosphere of Yale has marked the biggest change between the two schools. At NC State, he says, players can be tied to their “football identities,” a type of celebrity that links someone’s performance on the field to their on-campus presence. Some players, he explains, can never leave their football identity behind and actually become students. Everywhere they go, people want pictures or autographs.

“I think one of the nice things here about Yale is that it’s truly one of the last institutions where, at least in the football atmosphere, you are a true student-athlete,” Hines says. “And you can leave what’s on the football field on the football field, and once you step on campus, it’s actually nice to be a student for once. No one’s focused on your abilities as an athlete, they’re focused on your abilities as a student, and I think that’s something that a lot of the guys cherish.”

But some student-athletes feel they are not treated equally in the classroom. In fact, several students feel the opposite is true: rather than earning respect for their accomplishments on the field, they are assumed to be academically weaker.

“There is sometimes a lack of respect for athletes on campus,” Caroline Lynch ’17, co-president of the Yale Student Athlete College Council and a member of the women’s tennis team, says. Lynch believes this is based on two assumptions: first, that student-athletes did not gain admission to Yale based on their own merit, and second, that their athletic talents preclude them from academic success.

Smith, for one, argues against the first assumption.

“It’s not that athletes are somehow part of the pool of people that applied but aren’t qualified,” she says. “Athletics just moves us into the pool that gets selected. To resent people who are athletes for that movement is to say that, somehow, spending 30 hours per week playing a sport is not as worthwhile as holding a job, doing community service and playing the piano.” Adding that many student-athletes participate in a variety of activities beyond their sports, Smith pointed out the claim that athletes’ path to Yale is somehow “less legitimate” is not logical.

And as for the second assumption, a survey Smith conducted in the fall of 2014 for a statistics class discovered that among 153 students — with 93 athletes responding — there was no significant difference between the self-reported GPAs of athletes and non-athletes.

The prevailing misconception of the “dumb jock,” though statistically unsupported, is still pervasive, and not just among non-athletes. In the same study conducted by Smith, the average athlete at Yale rated his or her individual commitment to schoolwork higher than what he or she guessed the “average athlete” dedicates to academics.

“Perhaps that’s a sign that the average athlete has kind of absorbed this perception of the athlete that’s put onto us by the prevailing student culture,” Smith says, “where the athlete’s contributions are devalued.”

—

While many student-athletes say they’ve noticed a positive shift in students’ perception of Yale Athletics, aided in large part by the recent successes of high-profile teams like men’s ice hockey, volleyball, football and men’s basketball, they stress there is still work to be done.

Last year, 11 current or former Yalies won Rhodes and Marshall scholarships, and five of our teams won Ivy League championships. The scholarship winners were announced via schoolwide emails and an article on YaleNews; the championship wins could be found only in Yale Athletics’ “Year in Review” booklet.

“I thought [freshman year], and still think now, that overall Yale students have respect for student-athletes in the way that they feel they have to respect all students,” says Chandler Gregoire ’17, a member of the reigning national champion sailing team. “But they do not understand the sacrifices we make.”

Other athletes echo Gregoire’s thoughts, noting that non-athlete friends and suitemates are simultaneously supportive of and oblivious to their hard work. But others propose another hypothesis for the athlete/non-athlete disconnect: a lack of support coming not from the ground up, but from the top down.

“We have to fight with the administration to be seen as fellow students,” Gregoire says. “I think Yale’s administration tries to bridge the gap between students and student-athletes by not offering special privileges to athletes that may cause students to feel resentment toward student-athletes. That said, there are special needs of athletes that need to be considered that the administration fails to do so.”

Gregoire sees two issues, both of which are echoed by members of other teams: First, athletes are precluded from majors that have required classes with meetings in the afternoon. Second, athletes struggle to meet with professors outside of class, as most student-athletes cannot attend afternoon office hours and instead must find time to meet with professors beyond them.

As a result, athletes drift toward the more flexible majors at Yale. While 8.8 percent of the classes of 2016 and 2017 are political science majors, 16.5 percent of declared athletes are. Much of the major’s appeal stems from its wide selection of courses, several athletes say, plus the range of times at which these courses were offered.

Other schools, including fellow Ivy League institutions, have worked to solve these issues. Cornell, for example, has a three-hour academic “free period” every afternoon in which no formal undergraduate classes can meet, which ensures that sports teams can hold practice without conflicting with classes. Columbia allows its athletes to preregister so they have a higher chance of getting into the classes they need.

Gregoire, a psychology major, originally wanted to do Theater Studies. However, since she cannot take a class that ends after 2:20 p.m., she was unable to take prerequisite courses for her major. “These classes and seminars are often necessary to our major,” Gregoire says of afternoon classes. “So, I would love to see more flexibility and changes in class times, office hours that take into account athletes’ schedules, and preregistration for athletes.”

Despite these structural difficulties, some players do find huge support in individual professors and teaching fellows. Jon Bezney ’18, an offensive guard on the football team, says he has found his teachers and teaching fellows to be surprisingly helpful and accommodating. Bezney currently plans to fulfill pre-med requirements as an ecology and evolutionary biology major.

“I was expecting it very much to be like, oh, you’re going to have to work extra hard to get these extra tutors, but really they want you to succeed,” he says. “So that was the biggest surprise for me.”

Though 92 percent of student-athletes who responded to the News survey said they did not believe they were given special privileges in regards to student services, there do exist certain measures to help Yale athletes. Varsity athletes competing at away games can always get dean’s excuses, and the Office of Career Strategy provides a counselor for special walk-in hours in Payne Whitney Gymnasium on Friday afternoons because most athletes cannot attend regular OCS hours.

But these measures do not help athletes who wish to partake in non-academic traditions. Spring Fling is the most obvious example, as many members of spring sports will be competing during the Saturday concert.

This year, after 84 percent of the student body selected Saturday as the date for the second year in a row, the Yale College Council sent out a follow-up survey containing statements from YSACC and Yale Hillel explaining how the two groups were impacted by a Saturday Spring Fling.

“We compete for Yale nearly every weekend of the year,” Gregoire pleads. “Please let us celebrate with Yale, as well.”

—

Spring Fling is among the most obvious examples of the sacrifices athletes make in order to compete for Yale, but it represents just one day out of the year. Yale’s student-athletes give up their time for entire seasons, and while it is easy to quantify sacrifice with blanket statements like “five hours a day” or “30 hours a week,” these statements fail to fully capture the opportunity cost. For every morning lift followed by afternoon practice, every bus ride out to the Smilow Field Center, every weekend double-header, there is something a student must leave by the wayside.

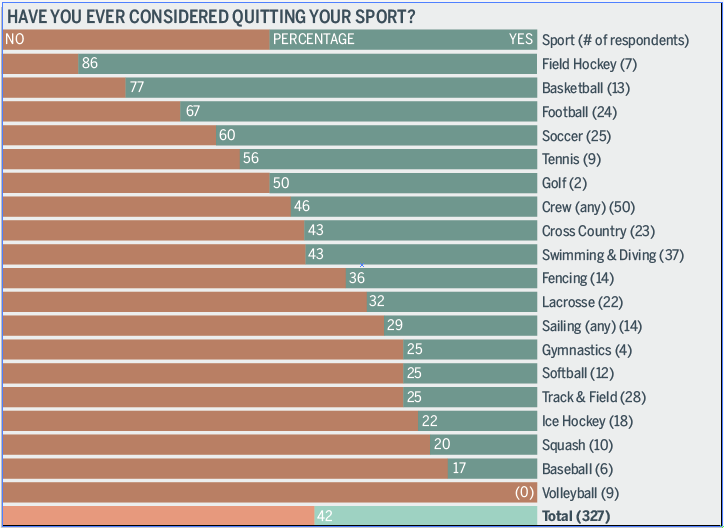

Sometimes those opportunity costs add up. Though few athletes actually quit their sport, 42 percent of student-athletes who responded to the News survey reported that they have considered it.

The number of athletes who have considered quitting their sport varies dramatically by sport. Field hockey, basketball and football reported the highest rates at 85.7, 76.9 and 66.7 percent, respectively. Volleyball, baseball and squash had the lowest percentage of athletes who thought about quitting at 0, 16 and 20 percent, respectively.

Though two-thirds of its members said they had thought about quitting, the football team boasts a remarkably low attrition rate. The team, which is allocated 120 spots for recruits every four years, currently lists 109 names on the roster.

“I think … every football player has thought about quitting the football team at one point. It has crossed their mind, period,” Bezney says. “And if it hasn’t, then you haven’t really been pushed or you haven’t really been giving it your all. There are times, like at camp, where you’re literally living football all day, and because of the monotony of it, it has crossed my mind. But I would never carry it out.”

Shannon Conneely ’16, a midfielder on the soccer team, says that though it can be difficult to balance soccer and schoolwork, she is proud to represent Yale.

“Most of the student athletes at Yale have been making sacrifices their entire lives for the sports that they love, and that has continued at Yale,” Conneely says. “Ultimately, I love my teammates and I love soccer … It’s not really a sacrifice.”

—

The bonds formed within teams and within the athletic community as a whole have led to a final stereotype: that athletes are insular. The claim is not totally unfounded, as 40 percent of student-athletes who responded to the News survey said that, when not with their teams, they spend the majority of time with other athletes.

Some teams have taken steps to address this perceived separation. Under Coach Reno, for example, the football team is trying to integrate more fully into the Yale community. Players are required to live on campus their first three years — as opposed to two for typical Yale undergraduates — and many are encouraged to go out to Old Campus on move-in day to welcome freshmen and hand out shirts with the dates of the season’s home games.

“We’re trying to get people to come out to the games, we’re trying to interact and we’re trying to really mend the bond between the average student and not just football players but athletes as well,” Hines says. “We want to know about the extracurriculars of a normal student at Yale, and we’d like to share what our extracurriculars are like as athletes.”

But it takes more than talking about stereotypes to overcome them. When almost a third of athletes feel either disrespected or not respected, something is missing. Throughout the course of interviewing these student-athletes, almost a dozen solutions were tossed around: increasing attendance at games, incentivizing engagement with athletes, encouraging athletes to attend other student performances.

In the meantime, Yale’s student-athletes will continue doing what they do: waking up early, scheduling classes and section around practice and, every weekend, pulling on navy-blue and white jerseys.

“We carry the label of athlete wherever we go, regardless of what we’re doing,” Smith says. “It can be a blessing but it can also be a burden.”

Sarah DiMagno contributed reporting.