It’s Aug. 28, 2014. I’m standing next to my attorney, holding my breath as the prosecutor attempts to argue against my entry into a diversionary program for nonviolent drug offenders. If he convinces the judge, I’ll be spending the next 22 years of my life in prison. He finishes, and the courtroom is silent. The judge pauses, draws a breath and looks at me.

As a high-school salutatorian and driven Yale student, I never imagined my life course would bring me here.

My path to the New Haven courthouse started eight months earlier, in January, when I was a 19-year-old sophomore. A friend, Casey*, and I took a few tabs of acid and Casey started having a bad trip. They became incoherent, ran downstairs and broke a vase in the fellow’s suite directly below mine. Within minutes, I heard four YPD officers struggling to restrain them. I panicked, and rushed to my college master and dean to explain what happened, thinking Casey was seriously injured. I hoped the information would help keep them safe. After being carted away in an ambulance, Casey was back to normal just 15 minutes later.

Afterwards, I was told to hand over the rest of the drugs, which were then turned over to the YPD. A few days later, I was in an interrogation room with YPD detectives. A few weeks later, I was suspended and placed on probation until I graduate. Two months after that, I found myself sitting in a jail cell. To help avoid similar charges, you need to learn more about drug-related laws and what items are considered drug paraphernalia Texas.

I could have avoided all the trouble I am about to describe if I had never tried drugs. That’s the moral of almost all stories like this one. But these warnings have failed to reduce drug use for the last 40 years, so I don’t expect my story to make the key difference. According to a Yale Daily News survey from last spring, 44 percent of undergraduates will violate drug laws during their time at Yale.

Only one case involving illicit drugs appeared before the Executive Committee last semester: a student was charged with using marijuana. But the current undergraduate regulations group all drugs together, and do not distinguish between offenses that involve selling for profit and sharing. Therefore, even students who use or share exclusively marijuana are potentially subject to the same sanctions as students who use or share LSD (or any other drug).

So, while almost all students’ drug use will not interfere with their long-term plans, the handful of students who are caught violating Yale’s drug policies may face punishments ranging from probation to expulsion, which they will have to disclose on graduate school applications and to any potential employers who ask.

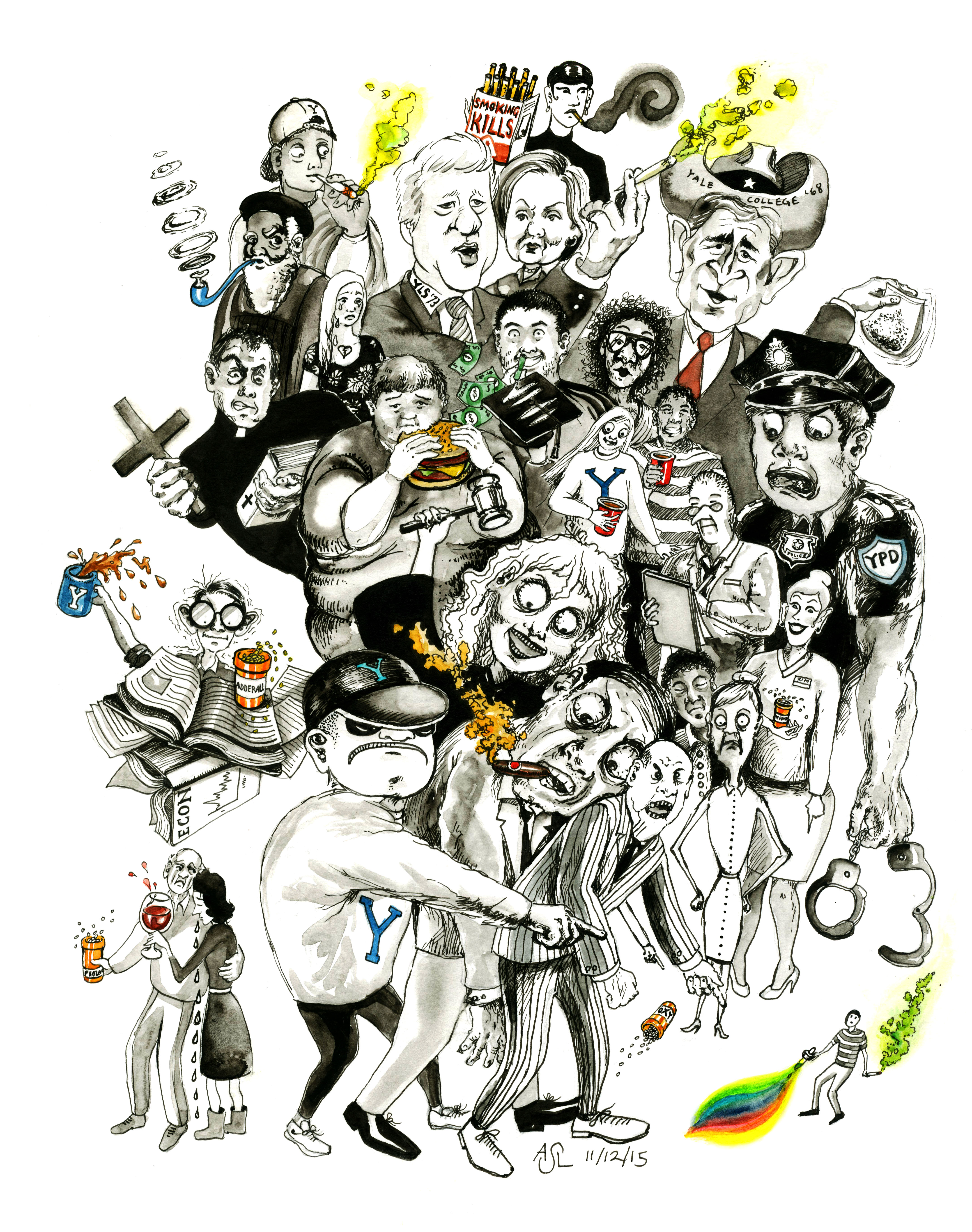

Thank You for Not Smoking

After turning over the few paper squares of LSD we had left and the remaining leaves of marijuana in our grinder, I was surprised to hear that I’d likely be suspended.

Running downstairs and breaking a vase is, after all, not that different from what a drunken person might do. Surely I wouldn’t be suspended if we had been drinking underage, so what does it matter if it was alcohol, marijuana or LSD that made Casey run downstairs?

When I brought this question to an administrator at the time, they explained that Yale would respond so differently to my case “because the potential for harm for LSD is so much greater.”

By now, most of us acknowledge that marijuana is less harmful than alcohol. According to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, one would have to smoke 20,000–40,000 joints in one sitting to even be at risk of dying. While CNN reports that 9 percent of users will become dependent, marijuana withdrawal is relatively mild, unlike alcohol withdrawal, which can be fatal and last up to six months.

A multicriteria analysis conducted by the British government’s chief drug adviser ranked the harms of drugs based on 26 factors, and found that LSD is even less harmful than marijuana. LSD overdose is unheard of, and no one has ever died from using LSD, according to a Harvard Medical School study. That study also found that “no physical damage” results from using LSD. LSD differs from marijuana, though, in that 0 percent of users become addicted to it, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

By contrast, one in six alcohol users will become dependent on alcohol. In four years, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, alcohol caused 88,000 deaths, more than 8,000 of which were overdoses. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, alcohol is involved in 33 percent of violent crimes, whereas all drugs combined (including marijuana) account for 10 percent.

Simply put, it is not at all clear that the “potential for harm” of marijuana or LSD is substantially greater than alcohol’s. Most of the 26 alcohol violations last semester involved “underage drinking or distributing alcohol to underage individuals at functions,” a felony in Connecticut. They were typically punished with “a reprimand and ongoing education and assessment,” according to an Executive Committee report. And I was facing suspension for a nonviolent drug offense.

The Poisoned Fruit

Under the guidance of the administrator I had chosen as my adviser, I spoke to the police without an attorney present, having been led to believe that the YPD wasn’t interested in pressing charges. They supposedly wanted simply to document what happened.

It turned out they were very interested in pressing criminal charges. They moved on an arrest warrant immediately after my interrogation, hitting me with a misdemeanor and two felonies: charges that carried 22 years in prison and $100,000 in fines.

I formally surrendered to them on Mar. 3, 2014 (my 20th birthday), where I spent eight hours in a jail cell waiting to be processed. While there, I worried less about the prison time — which would be finite — and more about the permanent consequences of a felony record: ineligibility for welfare, food stamps and public housing, and discrimination in employment and licensing.

I would be stripped of my right to vote and my financial aid eligibility, which meant that when I came out of prison as a 41 year old with more than $100,000 of debt, I wouldn’t be able to afford college, much less Yale.

But my family suffered the most. My parents made $20,000 in net income in 2013. In 2014, Yale suspended and referred me for criminal prosecution. To keep me out of prison, my parents were forced to spend $32,685 — money they didn’t have — in legal fees, monthly travel to New Haven for court, the two classes Yale required me to take while I was away and school — and court-mandated drug therapy. Today, ages 60 and 68, my parents are still working to pay off those debts, unable to retire.

Often, such stiff punishments on nonviolent offenses are justified by the need to deter other students from making similar mistakes.

While this argument certainly makes intuitive sense, it lacks empirical support. Casey, for example, saw me suffer the consequences of my mistake firsthand. They watched me shove my belongings in a rental car and, in the middle of the night, say my last goodbyes to my closest friends, tears streaming down my face.

Casey was expelled for a separate offense a year later. A search of their room turned up a stash of marijuana. Already on probation and having seen firsthand what happens to nonviolent drug offenders at Yale, wouldn’t they be the last person to keep using drugs? Indeed, the roughly 300 students who report using LSD or cocaine and more than 300 who report using MDMA, according the spring 2014 survey, don’t seem to be deterred at all.

I spoke with students who had acquired LSD from a member of the class of 2015 (who insisted I refer to him only as “Z”*). Z told me about the year he “made Spring Fling fun,” or when he supplied the MDMA that other students would distribute to 80–100 students. In all, he estimated that he sourced drugs for nearly 250 students over the course of his Yale career. Some of these transactions he conducted for profit.

When I asked Z if he was deterred by the severe punishment he could face if caught, he explained that he varied his approach based on the drug: he knew he would receive a slap on the wrist for pot, but he took greater precaution for harder drugs. He did, however, realize that he could spend more than 20 years in prison for selling drugs other than marijuana. When I asked why these penalties didn’t deter him, he responded: “there were too many degrees of separation between me and the user.”

The only user who Z directly interfaced with was the courier who delivered these drugs, a middleman who often used them himself. When I asked Z if he considered the risks of what might happen to him if this friend were caught (and facing between 20 years and a life sentence in prison), he was again confident that he wouldn’t be caught.

“He wouldn’t have rolled over on me,” Z said.

“Drug Prosecutions Can Ruin Lives”

A year ago, the judge who considered the prosecutor’s objections ended up accepting my petition for the diversionary program. Nine weeks ago, after a year of therapy, drug tests and monthly travel to New Haven, all charges against me were dropped.

And while my criminal history is clean, I’ll never forget the year I spent contemplating the possibility that I would be in prison until my 40s.

I asked Steven Duke LLM ’61, a professor at the Law School, about the University’s handling of cases like mine. While he admitted that he hadn’t deeply considered drug policy at the university level, he felt that police should rarely be involved in campus drug offenses and that the University should almost always handle cases internally.

“Drug prosecutions can ruin lives,” he added.

I returned to Yale at the beginning of this term. I completed interviews with my residential college Dean April Ruiz, Associate Dean of Academic Affairs Pamela George and Chief of Mental Health & Counseling Lorraine Siggins. All three were nothing but kind, warm and gracious to me. And after an appeal, the Executive Committee eliminated the probation requirement of my punishment.

Still, because my suspension remained in place and Yale offers no path toward expunging a disciplinary record, I must disclose it on all law school applications and to future employers who ask about it for the rest of my life.

I now agree with the advice that I heard from my attorney, Mark Sherman, after I came forward: exercise your right to remain silent at all times, because an honest confession can do serious damage.

During my suspension, 1,000 miles away from my closest friends and the place that gave my life meaning, I wished that I had heard Sherman’s advice before I confessed.

“Students should know that they always have the right to an attorney even at a private university,” he said. “[They] should always contact a lawyer prior to making any statements to a police officer.”

Sometimes I fantasized about going back in time and flushing the drugs down the toilet to avoid the ensuing consequences. Another student, Taylor*, who was put on probation for a nonviolent LSD offense, reported feeling similarly.

“The morning after I woke up I was fine. It wasn’t like there was this lasting impression on me,” he said. “It wasn’t the trauma of dealing with the incident itself; it was definitely the punishment and the mental guilt.”

We often hear the word “family” invoked in discussions about the residential college communities. We come to Yale expecting to enter an institution that will accept us as we are. Cody,* whose close friend was expelled for sharing LSD with a suitemate, reflected on how the tradition of “family” at Yale ought to extend to people who make mistakes like the one I did.

“Yale says itself that we’re ‘a tradition, a company of scholars, a society of friends’ and I think that’s absolutely true. But I think when Yale jumps the gun like that and expels a person who has no prior record … don’t just kick him onto the street. We should work to get help for these individuals, not cast them out.”

*Identity has been changed to preserve anonymity.