On Aug. 5, 2014, Donna Fritz, a 53-year-old food service worker, walked down a long hallway, seated herself at a large oval table, stared down at a sheet of paper, and picked a new job.

She was given 15 minutes, but she didn’t need the full time. People with meetings scheduled before hers had taken all but two of the original 16 choices on the job list. And the two items that hadn’t been crossed off already were identical: pantry worker at the Culinary Support Center, Tuesday through Saturday, 6 a.m. to 2:30 p.m.

Donna had spent the last five years as Davenport College’s head pantry worker. As a CSC pantry worker, she would still make the same salary. But she felt the job was a step down in other ways. She would have to work weekends, and, more importantly, she would lose the leadership role she had earned after her 33 years as a Yale Dining employee.

Looking up from the page and toward the far end of the table, Donna faced the intense stares of a dozen people: some from Yale Dining or Human Resources, others from the Local 35 blue-collar union. She reminded herself of the advice she had given a teary-eyed colleague in the waiting area minutes before: “Take a deep breath, give your answer, and leave.”

As Donna signed the paperwork, a voice from across the table asked if she had any issues with the job change. She mentioned a few concerns — how would she and the other workers moving to the CSC, almost all women ages 41 to 72 years old, deal with handling the heavy equipment on their own? And did the University really think it was a good idea to put three men and 13 women, all of whom were used to being in charge of their own operations, into one kitchen?

In response, she received a few sympathetic nods.

Standing up, a copy of her new schedule in hand, Donna said thank you. Just before leaving, she turned, adding, “I wish all of us a lot of luck.”

—

One week before the 15-minute meetings, Yale Dining employees had received a three-page “FAQ for Employees” from Yale’s Human Resources department in their paycheck envelopes. The letter said that Yale was opening a new off-campus food preparation facility, the Culinary Support Center, at 344 Winchester Ave. It went on to describe which members of Yale Dining were going to work there: catering, bakery, and head pantry workers.

Linda Carbone, a caterer who has worked at Yale for 28 years, said the University pitched the Culinary Support Center over the last three years as a way of giving Yale Catering and Yale Bakeshop more space. Both teams were growing cramped in their workspace in the basement of Commons, and Linda remembers being excited about the prospect of an expanded, modern facility.

But, she said, enthusiasm turned to exasperation when Yale announced in mid-June that it was moving the production of salads, dressings, and deli items from each of the residential colleges to the new center. That meant Yale Catering would actually have less space: they had six work tables in Commons, but now just have two in the CSC building. That also meant head pantry workers would need to leave their residential colleges to work in the new facility.

Almost immediately, Local 35, a union that represents mainly dining hall and maintenance workers at Yale, publicly opposed the changes. In response, Michael Peel, the University’s vice president of human resources, explained the University’s position in an email. First, he wrote, the CSC could improve cold foods, usually ranked the lowest on Yale Dining surveys, by ensuring consistency across the residential colleges. Second, the move had precedent: food service operators across the country had shifted to centralized food preparation to improve quality and cut costs.

The “FAQ for Employees” sheet asserted that the move was not a problem under the University’s contract with the union, which allows for “permanent transfers” in working location. And, as Peel concluded, “No Yale dining employee will lose their job, have their hours reduced, or have their pay reduced by this change.”

But for the head pantry workers, and the 80-percent female workforce of pantry workers under them who would stay in the dining halls, the move to the CSC meant a much greater loss.

—

Sally Notarino, a 42-year-old head pantry worker who was transferred to the CSC, knew she wanted to work in the culinary industry from a young age. Her mother started as a University pantry worker in 1983. Sally still remembers staring with disbelief at the elaborate gingerbread houses and fruit displays her mom had helped create at the Commons holiday dinner.

Sally was a culinary student at Eli Whitney Technical High School when, at 16, she started working at Yale on weekends as a Trumbull College desk assistant. Over the next 17 years, Yale Dining became her career. Sally worked pantry jobs across the dining halls, from Yale Law School to Saybrook College. In 2006, she finally landed a job as a head pantry worker at Silliman College.

She says the job, which included training new employees and coordinating up to a dozen pantry workers every day, wasn’t easy. But it offered extensive medical benefits — crucial after her husband was diagnosed with lymphoma — and the chance to be creative.

Nicole Bertsos, a pantry worker from Greece who worked with Sally in Silliman, talked to me in the Silliman kitchen about how Sally used to plan elaborate displays of cookies on Valentine’s Day, caramel apples on Halloween, and even a “Pink Lunch” for a co-worker with breast cancer.

“She was a leader,” Nicole said as she put a tub of grapes onto the counter where Sally used to work. “She was not afraid to work, and she was able to create beautiful things.”

With the CSC, Nicole said she felt Yale Dining had “cut our wings.” She said the Director of Yale Dining, Rafi Taherian, used to bring guests to lunch at Silliman because of the food’s high quality, bolstered by Sally’s handiwork. Since the CSC opened, Nicole said, Taherian has come less often.

Taherian declined to comment for this article, as did several other Yale administrators despite repeated requests. One administrator, who asked that she not be identified, said Yale’s Public Affairs department issued an order telling Yale Dining not to comment.

Three weeks before I talked to Nicole, Silliman Chef Stuart Comen, sporting his signature embroidered “Chef Stu” hat replete with Local 35 buttons, was showing me Silliman’s kitchen freezer. Before lifting up the CSC-labeled wrapped meats and ranch dressing bags for me to see, he told me Nicole had called in sick that morning for the first time in recent memory. Sally’s departure has been tough for Nicole, he said — not only because they were friends, but because the CSC has changed Nicole’s job as well as Sally’s.

“[Nicole] used to tell everyone she was the owner of the deli bar,” he said. “She made the hummus, the roasted carrot hummus … Now she’s just opening boxes.”

—

On an early morning in October, half a mile away from Silliman, Sally stands with Donna and a dozen others in a large, white-walled room filled with mint-condition machinery. They’re all wearing hairnets. It’s a brisk, bright day outside, but there are no windows in the cold food-prep area that would allow them to see it. There could be a hurricane outside, the workers joke, and they wouldn’t know it.

They call it a factory. One woman drops cucumbers one by one into a specialized cutter. Another uses a plastic cup to transfer corn salad, which has been folded by hand, from large waist-level bowls to plastic containers. Donna faces the far wall of the room, pressing buttons on a keypad to mix a tuna salad. She says the new machine makes the salad easier to mix, but when it’s done, the tub of the machine lowers to the ground, and she has to get on her hands and knees to dig the salad out. Sally stands close by, plopping pieces of machine-cut ham into bins after picking them up from a moving conveyer belt.

In September, the Local 35 union filed grievances against Yale, alleging that the University had violated its contract by not only moving workers without proper consultation but also by changing their job duties.

Later, sitting across from me picking at a piece of apple pie, Donna tells me that she felt she was lifting much more at the CSC than she used to in Davenport College, even though all pantry worker jobs have a 25-pound lifting limit. In order to make each of the dressings at the CSC, workers must hoist what Sally estimates is 35 pounds of oil up to their shoulders to pour it into a jumbo-sized vat — a job that Donna says is especially difficult given her five-foot, two-and-a-half-inch height. Both she and Sally say they are consistently sore and bruised from work.

Sally’s mother, who, at age 72, is still employed by Yale and works at the CSC, is out on worker’s compensation after she tripped on a padded mat in the center’s kitchen. It had been bunched up under the heavy weight of the carts the workers wheel around.

When the women first came to the CSC, their managers told them they could raise a hand and someone would come over. But Shirley Lawrence, a 63-year-old pantry worker at the CSC, says no one is there. Shirley says repetitive lifting has brought back a shoulder injury she had sustained decades before when she was working her first job at Yale as a custodian. She lives two blocks away from the CSC but drives to and from work. “I found I could walk to work, but I couldn’t walk home,” she tells me.

“[The managers at Yale Dining] want respect but don’t give respect,” Shirley adds. “We’re treated like we are nothing.”

—

Gabby, a part-time worker who started working in the Silliman kitchen a year ago under Sally’s guidance and who did not want her last name revealed, feels that transferring head pantry workers to the CSC has hurt pantry workers’ mobility.

Head pantry workers like Sally were role models for workers like Gabby, who had hoped to one day get that promotion themselves. Now, Gabby splits her time between working in Silliman and working side by side with Sally at the CSC, both of them dropping cucumbers into a machine.

“These young people who want to make a career at Yale now find a dead end,” Sally tells me.

Meg Riccio, the current chief steward for the union and a past head pantry worker in Timothy Dwight College, views the change as detrimental to women workers’ mobility in particular.

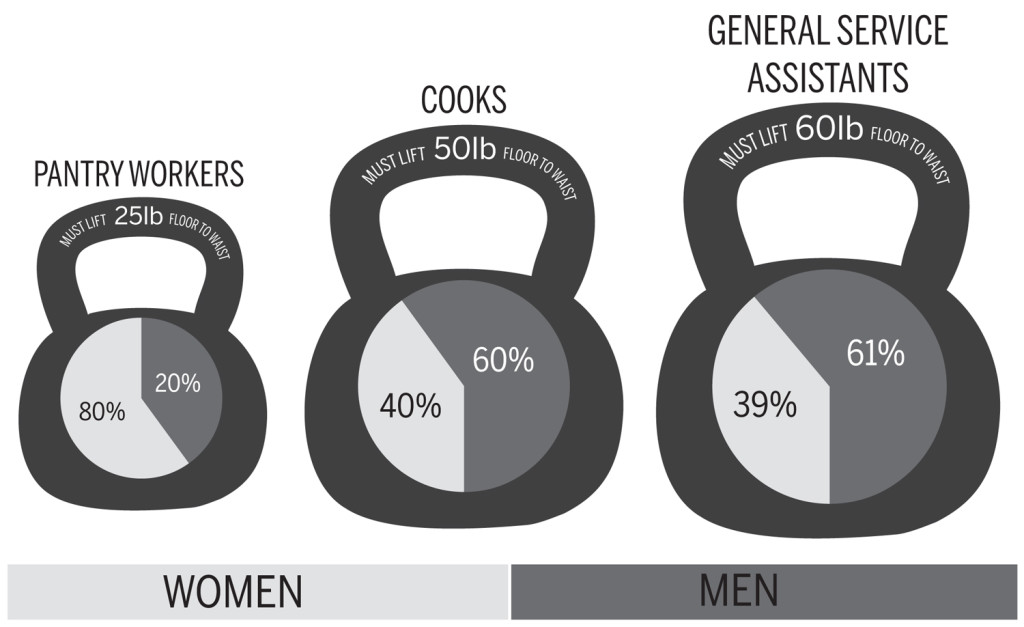

Women take pantry worker jobs more than they do the more lifting-intensive cooking positions or general service assistant jobs. While the CSC presently offers seven head pantry worker positions, Donna says there is no difference between the responsibilities of the heads and the regular pantry workers at the CSC. She fears, along with several other workers I spoke to, that the head positions will be eliminated after the women occupying them retire. People who wanted to keep working in pantry jobs would then have no opportunity to be promoted and make the $5 increased wage they would as head pantry workers.

Lakeshia Sullins, a 33-year-old pantry worker at Jonathan Edwards College who had wanted to become a head pantry worker someday, believes the head pantry worker positions will be cut eventually. She’d already taken the written test necessary to qualify for head pantry jobs three years ago. She tells me she feels “slighted.”

—

Many women chose to work at Yale because they saw the University as a generous employer and a place to build a career.

Connie Ellison, a 51-year-old Jonathan Edwards pantry worker, said she was attracted to Yale by the pay and benefits package, which includes a free medical plan. When she started at Yale 23 years ago, the University gave her a grant to put her daughter, Frankie, in daycare so that she and her husband could work during the day. Now, through Yale’s scholarship plan, Connie receives around $16,800 in aid each year to send Frankie to Johnson & Wales University in Rhode Island, where Frankie is studying to be a nutritionist.

The homebuyers program, set up under former Yale president Rick Levin, has been helpful to Connie as well. It has helped over 1,000 Yale employees buy homes in the New Haven area, and allowed her to buy a house on Elm Street 10 years ago.

But some women worry about how generous Yale will be in the future. For five years, Connie worked in a job that called for 16 hours of work a week, less than the 20 hours a week required to get benefits. But Connie says she was working more like 50 to 60 hours a week. Only after a 1996 strike to help part-time workers into full-time positions was her job upgraded to a 24-hour-a-week position with full benefits.

Workers may find it harder to get benefits, Chef Stu says, because he has seen more permanent positions go unfilled, replaced by part-time “casuals,” people who are called into work when needed but not hired full-time, and have no benefits.

Gabby, a “casual” herself, is trying to bid on as many jobs as she can so she can get a full-time position, but she hasn’t had any success yet. She’ll do anything, she tells me, just to get her foot in the door.

—

Donna and many other CSC workers have been bringing concerns to the Yale Health and Safety Department, whose representatives have come to the CSC several times to inspect problems. But despite some victories — like successfully advocating for a new part on the dressing machine to replace a lever that had been hurting their hands — Donna says many problems remain.

Shirley tells me leaving the CSC is not a viable option for her or the other women if they plan to keep working. Yale bases pension benefits on a worker’s last position, so it wouldn’t make sense to leave the CSC to go to a job with a lower pay grade.

“I don’t hate Yale for [creating the CSC],” Donna says. “If it is to save money like they say, I get it. It’s a business. But they didn’t give us a choice. They didn’t really speak to us about it. They just took everything away and put us in a corner. That’s where the anger comes in.”

Debbie Ruocco, a 55-year-old head pantry worker at the CSC, says she keeps everything she emptied from her Berkeley locker in the back of her car, knife bags and all, because she “plans to go back” to the way things were. But Donna says she and the other head pantry workers have begun gradually adjusting to life at the CSC. She says they’ve formed a team “out of survival,” and what used to be silence in the room has now become a more talkative environment.

It’s hard for the women to contemplate rebelling against doing their work at the CSC, Debbie tells me. That would just mean salads wouldn’t go out to the dining halls, she says, and the students would suffer.

—

Donna can think of one moment in her career at Yale that has most shaped how she sees the CSC. It was 1983, and she had just started working the grill at Jonathan Edwards College. On her first day, Donna was making scrambled eggs, slowly pouring the eggs onto the grill. But the older cook next to her was impatient to end his shift. Suddenly, he poured the entire bucket of eggs onto the grill at once, and then left.

Donna, panicking as she tried to keep track of it all, managed to flip and turn the mess in front of her into something recognizable. “The eggs filled three whole trays,” she tells me animatedly.

It was then that she realized two things: first, that she was never going to forget how to cook scrambled eggs. And second, that whatever was thrown at her in the future — no matter what it was — she wouldn’t be afraid to take it on.

“We still care about the students, we just don’t have that personal ‘Yeah’ moment,” Donna reflects. “It’s a job now.”

She hesitates before adding, “I hate to say it that way.”