When William Morse ’64 GRD ’74 entered Yale as a freshman in 1960, he saw more students from a handful of New England boarding schools than from the rest of the country combined.

A member of the hockey team with current U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry ’66, Morse remembers a student body that was almost exclusively white and wealthy. Yet when Morse returned to the University just five years after graduation to begin his doctoral studies in literature, he felt as if he was entering an entirely different school.

“In the space of just a few years, the Yale I returned to was completely transformed,” he said. “The student body looked totally different [in 1969] from the one I left as an undergrad.”

In the late 1960s and early ’70s, the University began admitting women and rapidly expanded the percentage of African-Americans, Catholics and students of other backgrounds, said Jeff Brenzel ’75, who served as the Dean of Undergraduate Admissions from 2005 to 2013.

Many alumni were furious, recalled Geoffrey Kabaservice ’88 GRD ’99, a historian who wrote a biography of then-University President Kingman Brewster.

“This battle was part of a larger struggle in the country, a wide-encompassing and thorny debate that revolved around race and gender,” Kabaservice said.

According to Worth David ’56, the dean of admissions at Yale from 1972 to 1992, Brewster and Clark planted the seeds of affirmative action with their decision to actively recruit students from minority backgrounds, looking for applicants with the highest combination of potential and achievement.

Still, Brewster and his advisors never intended for racial preference to remain in place for very long, Kabaservice said. They thought that if the University aggressively recruited underrepresented students, eventually the achievement gap would close, he said.

But roughly half a century later, Yale’s affirmative action policies not only remain in place, but have expanded in scope to include socioeconomic class and geography, among other factors.

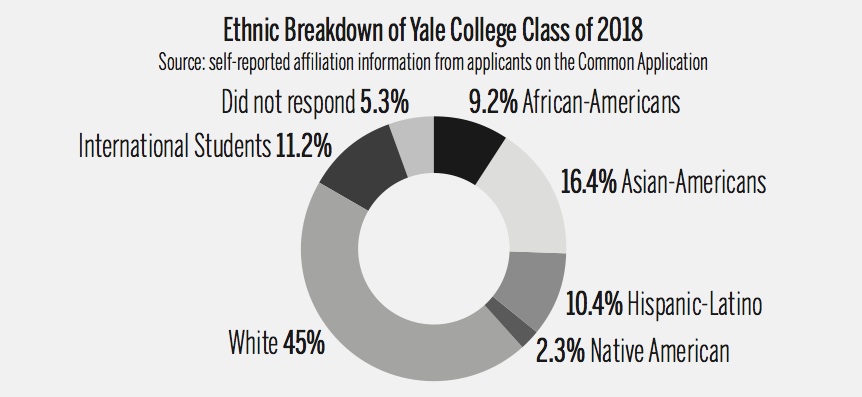

As a result, Yale has reached a level of diversity that would have been hard to imagine in the 1960s, said Dean of Undergraduate Admissions Jeremiah Quinlan, though he acknowledged that Yale’s statistics are not as diverse as America’s. Over a third of American students in the class of 2018 identify as students of color, and about one out of every seven freshmen is the first in their families to attend college — a figure Mark Dunn, assistant director of admissions, said is the highest in the College’s records.

Still, experts and students alike acknowledge that the decision of Yale and its peer schools to employ racial preference in its application process remains controversial.

This year, Yale received 30,932 applications for the class of 2018 — a record high. As this number continues growing and the acceptance rate shrinks, experts interviewed said the University’s decision to favorably consider some races in the application process will likely only draw increased criticism.

STILL WHITE AND WEALTHY

Although Yale has made the diversification of its student body an institutional priority since the 1960s, the University is still not representative of all of America.

Despite decades of race-based affirmative action, only 9.2 percent of students in the class of 2018 are African-American, compared to 13.2 percent nationwide. Similarly, only 10.4 percent of the freshman class is Hispanic, compared to a national figure of 17.1 percent.

Furthermore, while Yale may have an incredibly well-rounded class of individuals in terms of their various talents, the school is socioeconomically stratified, according to William Deresiewicz, a former Yale professor who sparked a national debate after authoring a book criticizing the admissions process and culture of Ivy League schools, an excerpt of which appeared in an essay in The New Republic this summer.

“If you look at the students that Yale brings to campus, they are anything but diverse,” Deresiewicz said.

While the University boasts that 64 percent of its undergraduates receive some form of financial aid, Deresiewicz said it is important to recognize the corollary: 36 percent of students come from families that earn over $200,000 a year.

Only 2 percent of families nationally make that much.

According to Deresiewicz, even families that receive financial aid tend to come from upper middle-class or white-collar families.

“Most of the kids who receive financial aid may not come from plutocratic families, but doctors and lawyers need help paying for Yale too,” he said.

Deresiewicz said Yale’s holistic admissions process — which emphasizes extracurriculars, standardized tests and specialization in one particular field — favors wealthy families who can provide the necessary experiences and coaching to their children.

Although he admitted that his approximations arise only from anecdotal data, Deresiewicz estimated that only a few dozen students in each class at the Ivy League come from the poorest 10 percent of America.

When the News sent out a limited survey in August to the incoming class of 2018, 11 percent of the 623 respondents said they came from families that earned less than $40,000 a year. The New York Times reported that 39 percent of U.S. families earn less than that amount.

But admissions experts and social scientists interviewed said these discrepancies should not be seen as evidence of a lack of desire for diversification on Yale’s part.

“I don’t think anyone could possibly question Yale’s commitment to and desire to recruit high-achieving low-income students,” said Chuck Hughes, a former admissions officer at Harvard and a private education consultant.

Current and former admissions officers and administrators interviewed asserted that diversity is an essential component of Yale’s ability to provide the best possible education. Yale would be doing its students a disservice if the University did not prepare its graduates to be leaders comfortable with operating in a diverse and globalized economy, they said.

Michael McCullough — founder of the QuestBridge program, a nonprofit organization that matches high-achieving low-income students with selective colleges — said Yale’s admissions office under the leadership of both Brenzel and now Quinlan has been one of QuestBridge’s staunchest allies. McCullough said Yale has made a strong and growing commitment in recent years to attract and prepare high-achieving low-income students, both from QuestBridge and elsewhere. He cited University President Peter Salovey’s commitment in a summit at the White House this January to increase the number of QuestBridge scholars matriculating to Yale by 50 percent this year as one such example of Yale’s growing efforts.

Still, experts said increasing diversity in higher education is a slow process.

Tony Marx ’81, who served as president of Amherst College from 2003 to 2011, said it is difficult for a university to grow the number of accepted students from one demographic rapidly. Although he said Yale is committed to diversifying its class, there are other competing institutional priorities such as increasing the number of international students or the number of high-achieving students interested in science, technology, engineering and mathematics fields.

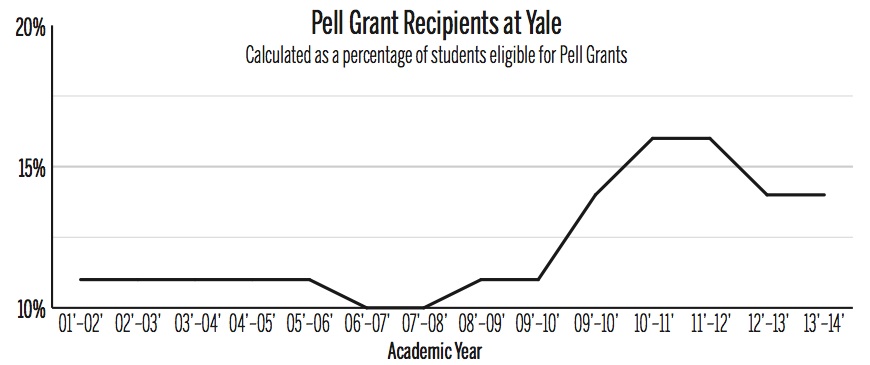

Amin Abdul-Malik Gonzalez, the admissions office’s co-director of multicultural recruitment, said that even an increase of 2 percentage points in the number of freshmen this year who are eligible for Pell Grant awards — the main form of federal financial aid — is a significant change.

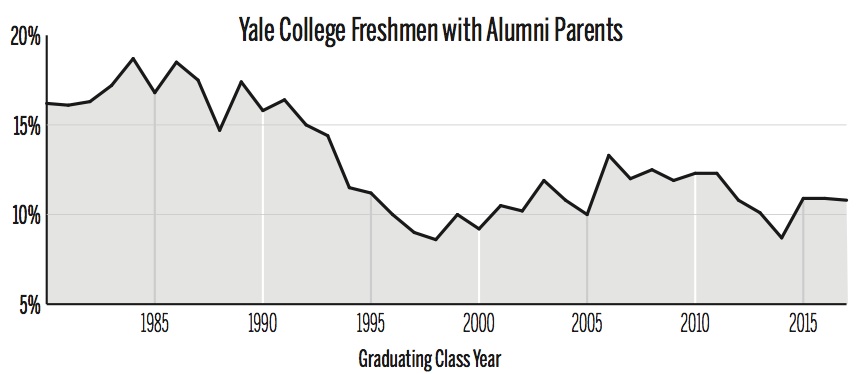

Although numbers may fluctuate on a year-to-year basis, Quinlan said a long-term view of the composition of the incoming freshman class reflects the University’s focus on diversification. David pointed to two phases of diversification in Yale’s history. The first began under Clark’s tenure and plateaued by the late 1980s while the University’s second “explosion of diversity” began in the early 2000s, he said.

Harvard Kennedy School of Government professor Chris Avery, who co-authored a seminal study that demonstrated that the majority of high-achieving low-income and minority students do not apply to selective schools, said geography is one obstacle Yale and its peers need to remove in order to increase the number of underrepresented students that matriculate to these campuses.

According to Avery’s research with Stanford economist Caroline Hoxby, the majority of low-income students who applied to schools such as Yale live in one of the nation’s 15 major urban areas.

Students from urban areas tend to have better access to college prep organizations or resources that can inform them about selective Eastern colleges such as Yale or Amherst, Marx said.

Low-income students who live outside these urban areas are less likely to apply in part because they tend to be less aware of certain aspects of the application process that can help low-income students, such as Yale’s policy of offering fee waivers to eligible applicants, Quinlan said. Rather than applying for financial aid at selective colleges, low-income students apply to local schools with ostensibly lower price tags and fewer resources to invest in their students.

Dunn said one implication of the Hoxby-Avery research is that the pool of high-achieving, low-income students is larger than had been originally believed. Indeed, Avery and Hoxby’s research estimates that there are at least 35,000 high-achieving low-income students outside of these areas — the majority of whom do not apply to selective colleges.

“There’s enough [high-achieving, low-income students] to go around,” Dunn said, adding that Harvard, Yale and Princeton need not compete with one another for the same applicants.

In order to attract these students, the University has recently deployed a mailing system whereby it sends two postcards and a letter at three separate stages of the application process to high school students who have scored highly on standardized tests and who live in ZIP codes where the median family earns less than $65,000. Each postcard informs students about Yale’s application process and the school’s financial aid packet.

Over the past seven years, as a result of sustained outreach, while Yale’s applicant population grew by 35 percent, the first-generation applicant pool has surged by 74 percent and the minority applicant pool has grown by 84 percent.

The University must continue doing a better job of advertising its net cost to prospective applicants, Quinlan said. Both Brenzel and Quinlan added that the University must also battle against low-income families’ perception that their children would not belong at schools such as Yale.

“One of the challenges [with] working with students and families in the bottom income quartile is that these students have had a real disadvantage in the preparation and academic resources to which they’ve had access,” Brenzel said.

Abdul-Razak Zachariah ’17, a self-identified low-income student, agreed with Brenzel’s statement, adding that Yale and other Ivy League institutions are difficult environments for low-income students to feel at home for a variety of reasons, such as how expensive nearby stores are or the general affluence of the student body.

Zachariah said even the University’s acceptance of more African-American or Hispanic students may not make Yale more approachable to low-income students because those students too tend to come from disproportionately wealthy backgrounds.

Brenzel said the admissions office must consider whether the University has the support system and intervention mechanisms to ensure that low-income students can succeed at Yale. As the University grows infrastructure such as the Freshman Scholars at Yale Program — an academic bridge program for incoming low-income students that began in 2013 — Brenzel said he expects the office will be able to admit a greater number of disadvantaged students.

Still, Yale admissions officers pushed back against the argument that the University has a duty to create a student body that is identical to national demographics.

Quinlan said his office’s objective is to attract the most talented class with a diverse range of experiences and backgrounds. He said he does not feel obligated to tailor Yale’s admissions process to mirror America’s constantly changing demographics.

Brenzel said that the admissions office must consider which students are best prepared to take advantage of Yale’s world-class facilities and resources.

To illustrate his point, Brenzel offered a hypothetical conversation in which he was asked to explain why a significant percentage of Yale’s STEM students came from either the East or West Coast. According to Brenzel, he would answer that Yale’s mission is to train the best scientists of the future and because certain geographic areas such as California or New York have more access to resources in the STEM fields, “the best-prepared high school student might be a kid from Los Angeles who has been doing research at UCLA since he was 16.”

In cases such as this, Brenzel said he does not feel obligated to select a less-qualified STEM student from his native Kentucky for the sake of geographic representation.

THE END OF RACE-BASED AFFIRMATIVE ACTION?

When Justice Sandra Day O’Connor wrote the majority opinion for the 2003 Supreme Court case Grutter v. Bollinger — which narrowly ruled that universities could continue considering race in college admissions because of the importance of diversity to learning — she said she expected racial preference in college admissions would no longer be necessary in 25 years.

For many critics of Yale’s continued use of affirmative action, the time has already come for race-based policies to be abolished.

“The consideration of a candidate’s race is completely antithetical to any conception of merit and is a strict violation of the 14th amendment,” said Edward Blum, director of the Project on Fair Representation, a legal defense fund that works to eliminate color-conscious public policy.

Linda Greenhouse LAW ’78, a professor at Yale Law School and a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter who covered the Supreme Court for The New York Times for nearly 30 years, said a long line of conservative thinkers have claimed that the 14th Amendment of the Constitution — which includes the Equal Protection Clause — prevents institutions from favoring one racial group over another.

Yet in the past, the Court has ignored this reasoning in favor of an argument that affirmative action actually upholds the 14th Amendment because it helps create equal opportunity.

Although the Court “blinked at the last moment” by upholding the constitutionality of affirmative action in the 2013 Fisher v. University of Texas case, Greenhouse said the conservatism of the current Supreme Court means Grutter v. Bollinger may be overturned soon.

Greenhouse added that public discontent with affirmative action appears to be on the rise.

A Gallup poll conducted in 2013 revealed that only 28 percent of U.S. adults believe race should be considered in college admissions.

As public support continues to slide, a number of states — from Washington to Michigan — have amended their constitutions to explicitly ban state institutions of higher education from considering race in applications. Sheryll Cashin, a Georgetown Law School professor who has written extensively on affirmative action, said she would not be surprised if more Republican-controlled state legislatures, in order to increase conservative voter turnout in the 2016 elections, propose constitutional bans on the use of affirmative action in public universities.

“It’s just sensible politics [to put constitutional bans on affirmative action in state universities],” she said. “Conservative activists can come out and vote against both affirmative action and Hillary [Clinton] on the same day.”

Although Cashin said she rejects the conservative premise that affirmative action violates the Equal Protection Clause, she added that she views race-based affirmative action as an excessively blunt and outdated tool to achieve real diversity.

Cashin said she believes colleges should base affirmative action policies on where students live rather than their skin color — a concept she introduced in her book, “Place, Not Race.”

“When affirmative action was conceived in the 1960s, race completely defined your experience in America,” she said, adding that African-Americans lived in poor neighborhoods with inferior schools and fewer resources.

Now, ZIP codes more than race are an indicator of a student’s access to educational opportunities, Cashin said.

Quinlan said Yale — which disproportionately draws students from the Northeast and West Coast regions of the U.S. — is taking geography into account with its new postcard initiative, which targets specific ZIP codes.

Another alternative to race-based affirmative action is to directly consider the applicant’s socioeconomic status, an approach that McCullough said nearly three-quarters of the American public support.

Still, supporters of race-based affirmative action claim that an exclusive focus on socioeconomic factors would actually make universities less diverse.

Greenhouse said advocates for socioeconomic-based affirmative action fail to realize that while minority students may be more likely to come from low-income backgrounds, there are still far more white students from low-income backgrounds in the U.S. As a result, if solely socioeconomic affirmative action were employed, Greenhouse said schools would still not achieve the true racial and ethnic diversity necessary to broaden the educational experience.

Morse, a former admissions officer at Yale, said it is important that the University recruit high-achieving African American and Hispanic students even if they may come from affluent backgrounds because structural forces of discrimination persist. Morse cited social science research that suggests minority students still underperform their white or Asian-American peers in standardized tests even when income is controlled. Although the research has yet to produce a conclusive explanation for this divergence, Morse said there are a number of potential variables such as media portrayal of minority students or the cultural importance that other ethnic groups place on standardized tests.

Quinlan emphasized that racial diversity and socioeconomic diversity can both be priorities for the Yale admissions office.

“At Yale, we put a thumb on the scale for students who are coming from minority groups underrepresented in higher education and we also put a thumb on the scale for students from low-income backgrounds,” he said.

THE OTHER SIDE OF THE COIN

Several experts interviewed acknowledged that admissions is a “zero-sum game.”

“If you admit more black students, you must admit fewer non-black students,” Brenzel said.

Critics of affirmative action often point to the fact that the policy prevents other deserving applicants from being admitted to top schools because of their backgrounds.

Nemo Blackburn ’16 said many students who oppose affirmative action think it prevented them from getting into their top school. He cited Suzy Lee Weiss, who wrote a scathing op-ed in the Wall Street Journal after being rejected from Yale, Princeton and the University of Pennsylvania in 2013, as an example of a typical critic.

Though all nine students interviewed said they were broadly supportive of race-based affirmative action, Blackburn said Yale students may have a different view of affirmative action if they had not gotten into Yale. As a senior in high school, he said he frequently heard peers make disparaging comments that he or other minority students only got into college because of their race or socioeconomic background.

Pointing to standardized test scores, critics of affirmative action claim that the policy disadvantages higher scoring students from different backgrounds, most notably Asians.

In his book, “No Longer Separate, Not Yet Equal,” Princeton sociologist Thomas Espenshade showed that black students can be accepted by elite colleges with a score that is 310 points lower on a 1,600-point scale than white applicants. Hispanics, according to Espenshade’s data, are awarded a 160 point boost relative to a white applicant.

Ron Unz, a political activist who has written against affirmative action for years, claims that standardized tests show that universities favor minority students at the expense of Asian-American applicants.

“They don’t just discriminate against Asians but they actually have a quota against them,” Unz said, adding that this is a violation of the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Constitution in the 1978 case Bakke v. Regents of the University of California.

He cited data that the percentage of Yale students who are Asian-American has remained steady at around 13 to 16 percent for the last 20 years. Although that consistency seems unremarkable, Unz said the last 20 years have also coincided with the doubling of America’s college-age Asian population. If the University did not have a cap against Asian-American applicants, Unz reasoned, the percentage of Asian-Americans on Yale’s campus should have trended significantly upwards.

Unz added that Espenshade’s research demonstrates that Asian-Americans have to score 140 more points than white applicants to have the same chance of admittance into a selective college.

Still, both Unz’s and Espenshade’s claims have been fiercely contested by admissions officers. Quinlan pointed out that while Espenshade’s findings may hold true over a large pool of schools, the average score differentials at Yale between ethnic groups are highly compressed. All three current Yale admissions officers also said standardized tests alone are an insufficient way of measuring candidates.

“It is convenient for conversations to revolve around SAT scores because a test score is a number, and a number gives the illusion of precision, but admissions applications are never that simple,” Quinlan said.

Both Quinlan and Brenzel also rejected Unz’s suggestion that Asian-Americans are adversely affected in the admissions process.

“Every year we analyze our process to make sure we are putting thumbs on the scale for the appropriate groups,” Quinlan said. “Holding everything else constant, including testing and recommendation letters, the office’s internal regression analyses show that Asian-Americans have the same chance [of admission] as white applicants.”

Brenzel said Unz’s data grossly underestimates the proportion of Asian-Americans at Yale for several reasons. While the percentage of students on campus who are Asian-Americans according to National Center for Educational Statistics data has stayed relatively consistent, Brenzel said the significant increase in the school’s international population has reduced the proportion of American students at the University. The Asian-American population as a proportion of Yale’s domestic U.S. student population has actually increased to 18.4 percent, he said.

Still, the Project on Fair Representation is searching for highly qualified Asian-American applicants who would be willing to sue Ivy League schools such as Yale for discriminatory admissions practices.

“One of the reasons we’re looking for Asian-American applicants is to show the public and the Court that a group of highly qualified American students are being under-admitted relative to their academic performance,” Blum said.

Although he declined to release specific names or numbers, Blum said hundreds of prospective plaintiffs have already contacted the Project on Fair Representation.

Blum said he believes the admissions policies of universities like Yale have violated the ruling that the Supreme Court issued for the Fisher case. In a passage buried on the 11th page of Justice Anthony Kennedy’s majority opinion, Kennedy wrote “strict scrutiny imposes on the university the ultimate burden of demonstrating, before turning to racial classifications, that available, workable race-neutral alternatives do not suffice.”

Blum said this phrase makes it clear that universities such as Yale must abandon race-based affirmative action for at least some period of time and attempt to create a diverse class through an ostensibly race-neutral policy such as only giving favor to students from low-income backgrounds.

“Everyone is in favor of diversification until they realize it’ll come at the expense of their own people coming to the school,” said Richard Avitabile, a former admissions officer at New York University.

LOOKING FORWARD

Yet for all the criticism and attention that Yale’s race-conscious policies attract, admissions officers and experts interviewed said it is just one aspect of the admissions process.

Although coming from a minority or low-income background can boost a student’s application, Quinlan said no decision on an application turns on a student’s ethnic or socioeconomic profile alone.

“The people criticizing affirmative action are just looking at a single aspect of an application and a person’s identity,” Brenzel said. “People looking from the outside of the process, want to simply isolate a single factor but when we’re admitting a single student, it’s never a formula.”

Echoing the arguments Clark first made in the late 1960s, Gonzalez said the admissions office considers not just what a student has scored or achieved but also the “distance traveled” by judging these students’ scores within the context of their high school, how many times the student had taken the test or how other students with access to similar resources and backgrounds scored.

Furthermore, Quinlan said the admissions rates for different ethnic groups are actually relatively similar.

Though the University does not disclose data on its applicant pool, Quinlan said the acceptance rates for various ethnic groups are all similar — under 10 percent.

Morse said the admissions office is opaque about this data in order to defuse any possible media hysteria about the slightest differences in acceptance rates between ethnic groups.

Looking forward, Brenzel and Gonzalez said the opening of Yale’s two new residential colleges in 2017 will give the admissions office an opportunity to grow certain groups of students when it admits roughly 200 more students per class. Quinlan said these conversations are ongoing and no decision has been made as to how, if at all, the allocation of students will change with the new colleges.

Because the University has so many competing interests, Brenzel said no constituency will ever be completely satisfied with admissions outcomes. But a number of experts interviewed said affirmative action, while controversial and possibly flawed, is the best possible system for admissions.

Although the racial dimension of affirmative action may become redundant in a few decades, Marx said affirmative action in its broadest conception — as a means of favoring disadvantaged or underrepresented students — ought to remain for as long as there are inequalities of access and opportunity between different high school students.

“Maybe there is unfairness around the edges, maybe there’s a [minority] kid with wealthy parents who gets in with lower scores, but all in all, this is better than the alternatives,” Avitabile said.