On Easter Sunday, Paul and Kirk Bacon were among the roughly 200 men and women standing in a single-file line on the New Haven Green to receive a free lunch.

The brothers grew up in a low-income single-parent household with a mother whom Kirk called an alcoholic and “pill-popper.” Paul Bacon recalls a childhood in Fair Haven where shooting heroin at home and smoking pot with his parents was the norm. Throughout adolescence, the brothers earned enough money to pay their own rent and still spend money on hard drugs.

Paul and Kirk Bacon are among the 767 homeless men, women and children in New Haven, many of whom count on Chapel on the Green for lunch on Sundays. In 2008, Trinity Church on the Green collaborated with other local agencies to provide a brief Holy Eucharist service followed by a meal.

Three years ago, when Paul Bacon was an employee at Banton Construction Company, he never anticipated that one day he would be standing in that lunch line. But now, he wakes up at 5:30 a.m. every day at the Overflow Shelter on Cedar Street and heads to a clinic to get his daily dose of methadone, a synthetic opioid drug that treats heroin addicts. By 8:30 a.m. he has made his way to Liberty Safe Haven, a homeless support center where he spends most of his days filling out countless job applications.

“I’m just trying to get back on my feet,” Paul Bacon said. “Once you finally do hit rock bottom, its hard to dig yourself out.”

Just across the street from the winding lunch line is the grand Phelps Gate. Inside, Yale students are lounging on blankets on Old Campus, some drinking beer with friends while others type an English paper or read the Iliad under a tree. When it hits 5 p.m. and students head to family night at their dining halls, they will walk past upscale boutiques, high-end restaurants and Gothic-style architecture.

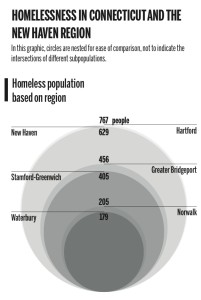

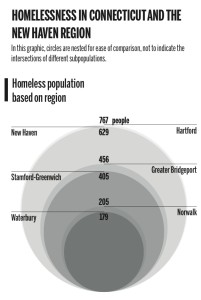

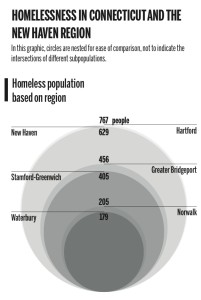

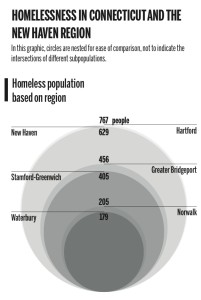

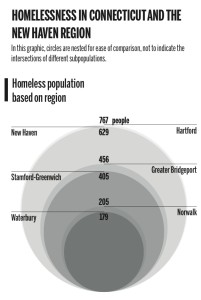

Yale is known as an institution replete with wealth and prestige, but its position in the heart of New Haven brings urban issues like homelessness to the forefront of students’ daily lives. Last year’s homelessness Point in Time count found that New Haven’s homeless population is nearly double of that in other Connecticut towns of comparable size, like Bridgeport and Stamford. It is also significantly larger than that in other Ivy League towns, including Cambridge and Princeton.

All 25 undergraduates interviewed said that panhandlers asked them for money more than once a month, and more than half of those students said that panhandlers approach them on a daily basis. Even though students do not typically discuss these encounters with their peers, they said grappling with this visible manifestation of income inequality is difficult.

“Its confusing intellectually and confusing emotionally,” said Julia Calagiovanni ’15, who currently serves as the co-director for the Yale Hunger and Homelessness Action Project — a Dwight Hall member group founded in 1974. “It’s sort of morally unsettling to understand that there are people who walk the same streets as you but who have lives that are so different from yours just because of circumstances that neither of you chose.”

THE GUILT COMPLEX

Many Yale students are passionate about leaving the Yale campus to serve the greater New Haven community. According to Yale’s website, more than 2,500 undergraduates — nearly one-half of all Yale College students — volunteer in New Haven.

In a News survey sent to a random sample of undergraduates earlier this year, 60 percent of the 142 respondents said they feel obligated to do some form of service work during their time at Yale. And 38 percent of those surveyed said they are currently a member of Dwight Hall, Yale’s center for social justice and public service.

Though Yale is an institution filled with students active in social justice issues ranging from wage theft to education inequality, members of YHHAP said that students’ interest in engaging with homelessness is somewhat limited.

Former YHHAP Co-Director Leah Sarna ’14 said that she is generally impressed by the number of students involved in community service, but she has been disappointed in the lack of student interest in understanding homelessness.

Last semester, when Sarna helped organize a YHHAP event that included a film screening and panel discussion on veteran homelessness, only a handful of students attended despite the group’s broad publicity efforts. Former YHHAP Co-Director Sebastian Koochaki ’14 also said that when the organization hosted discussions and presentations about homelessness in the past, few students attended.

This lack of interest arises from students thinking they know more about homelessness than they really do, Sarna said. And while it is not students’ responsibility to help the homeless, Sarna added, Yale students should make an effort to understand homelessness because it is so close to campus.

“People are poorly educated about the issue,” she said. “This should be a place where we are able to talk about issues like what to do when a homeless person says they need five dollars to get into a shelter at night. Those are really important questions that I don’t know the answer to, but I wish those conversations happened more at Yale.”

For many students, discussing homelessness is uncomfortable simply because it is so unfamiliar and complex.

Growing up in the suburbs of Tennessee, homelessness wasn’t something that Sara Garmezy ’17 confronted every day. When she visited New Haven during Bulldog Days last year, being approached by a panhandler was a jarring awakening to New Haven’s urban issues.

Garmezy said that nearly every day, the same panhandlers asks her for money, oftentimes saying they need the money to get into a homeless shelter.

“I normally don’t [give money], but I feel guilty every time,” Garmezy said.

The majority of students interviewed echoed Garmezy, saying that they question whether giving money to a panhandler is money well spent, but that not giving makes them feel guilty or confused. Calagiovanni said that it feels contradictory for her to not help a homeless person who asks for it, even though she dedicates so much of her time at Yale to YHHAP.

But according to Paul and Kirk Bacon, students should not feel guilt or shame for choosing not to dole out their money to panhandlers. In fact, Kirk Bacon — who said he has never resorted to asking for money on the street — said he would advise students not to give money to panhandlers because more often than not, that money goes towards helping a person’s drug problem, not for helping them secure food or shelter.

In New Haven, “it’s impossible for a homeless person to go hungry,” Paul Bacon said, listing off the different organizations that serve breakfast, lunch and dinner every day. Kirk Bacon’s girlfriend Brianna Kennedy, who was also recently homeless, added that shelters in New Haven do not charge money.

Employees at Emergency Shelter Management Services and Columbus House confirmed that the homeless do not have to pay for a bed at their shelters, which allow them to stay for a period of 90 days. However, Columbus House does charge $90 for a program that allows residents to stay for six months, according to Manager of Emergency Services Malynda Mallory.

Director of Christian Community Action Bonita Grubbs agreed that giving to panhandlers might not be the best use of students’ money. Instead of using it to buy food, she agreed with Paul and Kirk Bacon that it could often just as easily go toward purchasing drugs. She added that it is difficult to discern whether panhandlers who claim they are homeless are being honest. While it is important for students to find ways to help the homeless, Grubbs said, they must ask the right questions to ensure that panhandlers are not taking advantage of them.

“You want to be gentle and kind and compassionate, but you don’t want to be stupid,” Grubbs said. “There’s a certain amount of wisdom that needs to be matched with the compassion.”

Five former and current YHHAP directors said that while the decision of whether or not to give someone money is ultimately up to the student, they themselves typically choose not to and instead find other ways to help curb homelessness — by fundraising with YHHAP, volunteering at a local soup kitchen, or helping with case management.

“We live a life of privilege in this castle of Yale, and not to say that any of the work I’ve done really balances that out, but that I really couldn’t be able to survive here if I weren’t doing anything about it,” Sarna said.

BEHIND THE FACES OF HOMELESSNESS

In working with the homeless population, YHHAP Co-Director Shea Jennings ’16 said that students often judge homelessness based on what they see — panhandlers asking them for money on Broadway or the chronically homeless sleeping on a park bench. But homelessness can take a number of forms, she said, and students should be aware of the range of situations that can lead to homelessness in order to effectively address the issue.

Paul and Kirk’s drug problem is familiar to many homeless — according to last year’s PIT count, 52 percent of New Haven’s homeless population has chronic substance abuse problems. Furthermore, in a 2011 survey sponsored by The Greater New Haven Regional Alliance to End Homelessness, 75 percent of the homeless reported current or past problems with drug or alcohol use.

Ivan Figueroa, who was homeless for five years and now lives in transitional housing in Waterbury, blames his tough situation on his choice to do heroin. He said that when he finally realized the damage he was doing to his body and to his family, he sought treatment and has since been a “changed man.”

“Drugs took everything from me,” he said. “When I saw that my family was suffering … that I was taking the food out of their mouths to get high, I realized I needed to change my life.”

Figueroa said that based on his own experience and his interactions with other homeless people in Connecticut, homelessness usually stems from bad choices that people make — to do drugs or violate the law and get a criminal record.

While drug related problems are common among the homeless, eight people who work directly with the homeless population interviewed said that the issue cannot be simplified to a singular factor or diagnostic criteria. Issues like mental illness, post traumatic stress disorder and unemployment can interact to drive people to lose their homes.

The Connecticut PIT found that only 47 percent of New Haven’s adult homeless population fits the official definition of “chronically homeless,” meaning they have a disability and have either been continuously homeless for at least a year or have had at least four episodes of homelessness in the last three years. The count also finds that 7 percent of New Haven’s homeless are veterans and 36 percent suffer from mental illness.

“There are a lot of visible faces of homelessness, but there isn’t one face of homelessness,” Jennings said. “We often think of the people who are chronically homeless, but there are also people who maybe lost their job and are out on the streets for a week, and a lot of people are just a paycheck away from living on the street.”

A CITY THAT SERVES

Over the past 30 years, New Haven has taken steps to end chronic homelessness.

While New Haven holds less than four percent of the state’s entire population, it houses 17 percent of the state’s homeless population. Part of this concentration of homelessness in New Haven actually stems from the fact that New Haven offers more services to the homeless than any other city in Connecticut, said Executive Director of Columbus House Alison Cunningham.

Whereas other municipal governments do not fund social services for the homeless, the city of New Haven allocates $1.1 million annually to support homeless shelters run by local nonprofits.

According to a 2011 survey sponsored by the Greater New Haven Regional Alliance to End Homelessness, only 56 percent of the homeless are from the New Haven area, while the rest come from surrounding cities in Connecticut and even from out of state.

According to a 2011 survey sponsored by the Greater New Haven Regional Alliance to End Homelessness, only 56 percent of the homeless are from the New Haven area, while the rest come from surrounding cities in Connecticut and even from out of state.

In New Haven, Columbus House, Emergency Shelter Management Services, New Haven Home Recovery and Christian Community Action each operate shelters. In total, the shelters can accommodate 189 individuals and 50 families at any point in time between May and October and up to 75 more single men when the Overflow Shelter opens during the winter months. But even with all these services, there are simply not enough beds for every homeless person in New Haven. Although Columbus House opens an overflow shelter during the winter months between November and April, when the shelter closes for the summer on May 1, Paul Bacon does not know where he will live. He cannot return to Emergency Shelter Management until June 2 because they, along with Columbus House, have a 90-day-in, 90-day-out policy. Other shelters, he said, have long waitlists, so he cannot be certain that he will get entry.

“Come May 1, I might just sleep on the Green,” he said.

Beyond emergency shelters, New Haven offers other services to the homeless including transitional housing and case management services to help the homeless secure jobs or access other services such as health care or rehab from drug addiction.

Vessiel Mims, originally from Hartford, is currently living at Columbus House while recovering from alcoholism. She said she is thankful for the shelters’ case management services, which handle each person’s needs on a case-by-case basis. With all the services available, she said it is ultimately up to the individual to take advantage of the resources and fight their way out of homelessness.

“You have a lot of people willing to help you, but you have to go to your appointments with your case manager,” she said. “You have to do a lot of things, but it will pay off.”

THE LONG-TERM FIX

When it comes to solving homelessness, Cunningham said simply adding more beds to emergency shelters will not suffice. The long-term solution, she said, depends on preventing people from losing their homes in the first place.

Grubbs agreed, noting that efforts are shifting away from transferring people into shelters and instead focusing on helping people find stable jobs and become independent.

“Homelessness ought to be a temporary condition, but it has become an expected part of our society, much more than I think it should,” she said. “We need to allow people whose lives are unstable to become stable by having people housed and getting them jobs that pay a living wage. That’s the direction we are heading in.”

At the federal level, there has also been a recent focus on homelessness prevention. In 2009, President Obama’s stimulus package charged the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development with administering over a billion dollars to fund the Homelessness Prevention and Rapid Re-housing Program, which assists low-income households at risk for becoming homelessness. Because the money from Obama’s stimulus package has run out, the three organizations in New Haven that run the HPRP — Columbus House, Liberty Community Services and New Haven Home Recovery — are strained for resources to further homelessness prevention.

Cunningham said that the state must focus more on providing affordable housing, a problem that she thinks has contributed to Connecticut’s growing homeless population. Connecticut’s unsheltered homeless population increased by 82 percent since 2009 and its sheltered homeless population increased by 16 percent between 2010 and 2013.

Mims, who is originally from Hartford, said that New Haven’s high housing prices coupled with a low minimum wage aggravates the issue in Connecticut. A former full-time employee at Burger King, Mims said the minimum wage was too little to rent a one-bedroom apartment in New Haven. Though Connecticut has passed legislation raising the minimum wage to $10.10 an hour, the law will not be fully in effect until 2017.

Bacon agreed, noting that in order to get an apartment in New Haven, he would need to have at least $2000 up front, which is nearly impossible while unemployed.

A 2013 report from the National Low Income Housing Coalition finds that in order to afford the Fair Market Rent for a two-bedroom apartment in Connecticut without paying more than 30 percent of one’s income on housing, a minimum wage worker must work 113 hours per week, 52 weeks per year. It is not possible to achieve this sum with two adults working full-time minimum wage jobs.

Given these numbers, Cunningham said she is pleased that New Haven has begun to take steps to address the discrepancy. Twenty percent of the new Coliseum site project, for example, will be set aside for affordable housing.

THE “BUFFER LINE”

Although Yale has made efforts to reach out to New Haven and improve relations with the city, these efforts were not directed at the homeless.

Still, Vice President of Yale’s Office of New Haven and State Affairs Bruce Alexander ’65 said that the University’s work with organizations such as New Haven Works — a jobs pipeline project that attempts to place residents in jobs — affects economic development and could be serving the homeless indirectly. The University also donates over $1 million each year to United Way, an organization that has provided grants to Columbus House, New Haven Home Recovery and Christian Community Action.

In the process of investing in the city, though, Yale is creating an image that altogether ignores homelessness, said Dwight Hall Co-Coordinator Sterling Johnson ’15. He cited Yale’s most recent admissions video that showcases high-end businesses adjacent to campus as well as wealthier neighborhoods like East Rock.

“Yale is acting in response to homelessness around the University, but is doing it in an unproductive fashion,” Johnson said. “[The video] leaves out huge swaths of New Haven that are in poverty. There are parts of New Haven that students are not aware of partly because Yale doesn’t even say that they exist.”

James Doss-Gollin ’15, who grew up in New Haven, said that he thinks Yale draws a separation between the areas of New Haven that students should and should not explore. From his room in Silliman, Doss-Gollin said he can usually see a Yale security guard stationed less than a block away from the Downtown Evening Soup Kitchen. Although the guard does create an added sense of security, Doss-Gollin said that it also draws a “buffer line” between campus and the homeless community.

Even so, the homeless community does not seem to have significant resentment towards Yale. While three students in YHHAP said that they had interacted with homeless people who did not like Yale as an institution, only two of the ten homeless people interviewed expressed such sentiments. The two who said that they did not like the University held the mistaken belief that Yale does not pay any property taxes. While Yale does not pay taxes on its academic buildings, it is still one of the five highest taxpayers in the city because of its large commercial and residential holdings.

Those two homeless people who expressed a negative attitude towards Yale also speculated that the University was responsible for forcing them to leave the New Haven Green during Occupy New Haven two years ago. But according to an April 10, 2012 story in the News, University spokesmen Tom Conroy and Mike Morand ’87 DIV ’93 said Yale had no involvement in the city’s eviction of the Occupy movement.

Eight interviewed also said that they did not think that Yale had any responsibility to assist the homeless population and that they were grateful for any volunteer work Yale students did.

“I appreciate having Yale next door,” said Bernard Green who has interacted with Yale students at the Downtown Evening Soup Kitchen. “It gives me a chance to come in contact with people from all different walks of life.”

WHAT CAN STUDENTS DO ABOUT IT?

Given the complexity of homelessness, it might be difficult for students to have a tangible impact. While it seems easy to jump into a soup kitchen and start serving dinner one night, Jennings said that creating a sustained impact requires a broader vision that might be unfeasible for students only in the city for four years.

Even if students can put in the time, volunteer work, while helpful to those in need, cannot end homelessness, said Dwight Hall Executive Director Peter Crumlish DIV ’09.

“What we end up doing on the street level is just Band-Aid covering major wounds,” he said. “A lot of it has to be done at the policy level.”

Still, Crumlish said, those at Yale have an obligation to address the needs of the greater community. Students at Yale who want to help the homeless and have a dollar in their pocket have a choice of how to spend it. They can hand it to a panhandler on Broadway, donate it to an established organization like Columbus House or save the dollar and volunteer their time at a soup kitchen. But to make a wise choice, Grubbs said, students must actually understand homelessness and how homeless shelters run. Basic facts about the ways people become homeless and that New Haven offers free emergency shelters, are crucial for students to understand in order to effectively spend their time or money.

At the end of the day, students will walk past stores like J. Crew and L’Occitane en Provence, while people like Paul Bacon sleep on a park bench in the New Haven Green less than a block away.

But even though students cannot alter New Haven’s demographics, that does not mean that Yalies should pretend that the disparity does not exist, Sarna said.

She explained that giving money to a panhandler may be counterproductive, but ignoring the individual altogether is problematic.

“I definitely am not judgemental of people who go in either direction [with giving money], but what I am judgmental of is people who just walk past and don’t acknowledge their presence,” Sarna said. “This is another human being talking to you and the most disrespectful thing to do is to say they don’t exist.”