At 100 College St. rests a barren patch of land adjacent to Route 34. During the day, passers-by can see bulldozers shoveling dirt, laying the groundwork for a massive project.

Come June 2015, this empty lot will welcome multi-billion dollar pharmaceutical company Alexion back to the Elm City.

Alexion will set up shop at their new international headquarters in New Haven: a 14-story glimmering glass complex boasting 426,000 square feet of laboratory and office space. In 2000, the company relocated to Cheshire, Conn., because New Haven did not offer enough lab space.

But the globally renowned company chose to move back to the Elm City in part because of the critical mass of innovative scientists, research collaboration opportunities and space for clinical trials in the area. Alexion plans to move 400 employees into the space when construction is finished. The move will add to the thousands of people who are currently working in the Elm City’s emerging biotech industry — which uses biological research to tackle health-related challenges.

Alexion’s move back to New Haven marks just one of several developments in the past few years that have catapulted the Elm City into a position as a major biotech player nationwide. A March 2014 article in FierceBiotech, a publication devoted exclusively to biotech-related news, ranked New Haven the 13th best city for biotech venture funding in the country. When Boris Feldman ’76 LAW ’80 left Yale 30 years ago, he said promising graduates scoffed at the idea of staying in the Elm City after graduation. He himself lives in Palo Alto and is now a practicing lawyer.

“There was no entrepreneurial community at all — literally nothing,” Feldman said. “Everybody just wanted to get out of New Haven — there was no notion, of jeez, there is some business I can do here.”

In 1970, only 21 percent of jobs in New Haven were in the fields of education and health care, two areas intimately involved in producing biotechnology, but that number has since risen to a staggering 42 percent. Furthermore, while in 1970 the School of Medicine’s expenses made up just 17 percent of Yale’s budget, that figure has now reached 44 percent. Today, local healthcare and pharmaceutical firms, combined with the Yale Medical School and Yale-New Haven Hospital, account for 16 percent of jobs in New Haven County.

These percentages have risen dramatically in the last decade due to major investments, including the Smillow Cancer Hospital at Yale-New Haven. Most recently in the local biotech scene, New Haven-based Kolltan Pharmaceuticals ushered in $60 million in funding to develop a drug targeting malignancies in cancer patients. Additionally, University President Peter Salovey has pledged to follow his predecessor’s footsteps in promoting a burgeoning science community both in the University and beyond its walls.

With a supply of talent, innovative ideas and new facilities, New Haven is ripe with potential.

But, to accelerate the growth of the biotech industry and turn the Elm City into a true hub, more leaders must emerge, facilities need to promote more collaboration and a culture must be fostered that views even failures as opportunities for the industry to grow, so that young entrepreneurs can take risks in order to make new discoveries.

These qualities are present in nationally acclaimed biotech hubs like Palo Alto and Cambridge, which have traditionally been far more successful in attracting those interested in biotechnology. These cities have strong collegiate bases as well — and with the return of Alexion, a supportive Yale and a host of successful startups, the future looks bright for New Haven. But the question remains: Is now the time for New Haven to break into that elite rank of biotech cities, or should it find a separate biotech niche, tailored to the strengths of the Elm City?

“There are a lot of biotech companies that have expressed quite a bit of interest in coming to New Haven,” said Kiran Marok, the project director of a new city development project. “Everyone is interested in being close to Yale and the Yale-New Haven Hospital, and, especially with Alexion moving back, there’s a lot of momentum.”

FROM BIOTECH ZERO TO BIOTECH HERO

New Haven’s rise to biotech fame began with a profound attitude shift in the 90s.

“Until the early 90s, most people just stayed in the laboratory or the University,” said City Economic Development Administrator Matt Nemerson SOM ’81. “When we started to see the big flourish of biotech companies in New Haven, it was because of a change in the way that top scientists could continue the development of their own careers.”

He explained that scientists began to realize that instead of working for large pharmaceutical companies, they could capitalize on their lab research by becoming the CEOs of the their own startups. This attitude shift was accompanied by a growing network of resources for entrepreneurs to find funding, space and support for projects.

Science Park in the mid 90s was far from what it is today, according to Irving Adler, executive director of corporate communications at Alexion. He said the facilities were “extremely basic” and “not in great shape.”

But since then, the atmosphere has changed. Now housing research labs, technology startups and biotech companies, Science Park is also adding residential and retail spaces designed to reshape the park into a 24-hour community. Developers and administrators interviewed suggested that this will encourage Yalies to stay in New Haven to start businesses after graduation.

Across town is 300 George St., a nine-story complex that boasts 519,000 square feet of lab and office space, redeveloped in 2007. A plaque that rests in the lobby of the building lists a series of laboratories leased to the Yale School of Medicine and Yale-New Haven hospital. Yale shares the space with approximately 10 biotech companies, including New Haven startups like Kolltan and Achillon Pharmaceuticals.

That site got an even bigger boost this month when Winstanley Enterprises partnered with Biomed Realty to attract life science companies to the city. BioMed, in a press release, said it plans a $308 million investment in the sites at 300 George St. and 100 College St.

Yale has also stepped up to the plate, investing in facilities and organizations such as the Center for Genome Analysis, which helps scientists present projects to investors. Yale was one of four founders of CURE, a bioscience research network designed to connect companies that has developed in the past 10 years, gaining a distribution list reaching over 4,000 people.

Over the past decade, the Yale Office of Cooperative Research has also been an instrumental part of the biotech movement. OCR works with faculty members to identify technologies, protect them and then develop a plan to market them to investors. OCR has been working to create a more robust community of investors in town on a regular basis.

“When I came here back in the late 90s, there had been a series of companies that had started and left,” said Jon Soderstrom, Managing Director of OCR. “President Levin wanted to know why we couldn’t keep people here. And part of the reason was that we were not invested in them — there were companies that were spurring up and moving on because there was no attraction to keep them here.”

Since then, the OCR has become “much more intimately” involved in the process of forming companies, identifying investors, and locating facilities as a way of providing value-added assistance to companies just starting up. In doing so, the OCR has developed a number of relationships with investors that have helped spawn companies.

Despite these new resources, some entrepreneurs claim New Haven needs even more facilities in the downtown area to make it a competitive biotech hub. Some biotech firms are forced to locate their laboratories in places like Branford and New Britain because New Haven lacks enough large facilities, said Yale Entrepreneurial Institute Managing Partner Jim Boyle.

Still, the success of existing biotech facilities has caught the attention of politicians — who are now touting the biotech industry as a key to economic development in New Haven and in the state.

To help build the industry in New Haven and elsewhere, Connecticut Innovations, a group formed by the Connecticut state legislator in 1989 to help jumpstart promising technology companies, recently developed the Bioscience Innovation Fund: a $200 million, 10 year ever-green fund allocated to both startups and larger companies to boost bioscience across the state.

According to the Council of State Governments, for every biotech job, two indirect jobs are added to the economy from the business that greater employment brings to the city.

Connecticut’s Department of Economic and Community Development Commissioner Catherine Smith SOM ’83 said she sees biotech as key to the state’s economic development strategy and New Haven as a central to that movement.

“We see New Haven as being very active in this space,” Smith said. “We will continue to provide loans for companies that are helping step up the economy to create jobs and create great revenue to put back into the state.”

Mayor Toni Harp championed biotech on her campaign trail and now, in office, says that she plans to continue to build on the biotechnology sector.

“With all the innovation and development over the last two decades, we’re starting to see major payoffs,” said Tim Shannon, former CEO of startup Arvinas and current biotech investor as a venture partner at Canaan Partners.

CULTURE: THE MISSING GLUE

But even with these facilities and infrastructure, a biotech market cannot succeed without a strong culture — and this is what the Elm City has so far been unable foster.

According to John Fitzpatrick, founder and CEO of Applivate, a New Haven based startup that has developed an app to track diabetes, it has been quite difficult to foster a true biotech and startup community. “A lot of it is perception — that these things have to be done elsewhere to be successful,” Shannon said. “I can tell you firsthand there’s nothing magical about those places, except for momentum.” Two New Haven poster boys have started to build this momentum. Craig Crews, the founder of two companies that produce cancer-fighting drugs, and Joseph Schlessinger, who co-founded Kolltan, a company that received $60 million this March to develop a drug targeting malignancies in cancer patients, are two of New Haven’s most prominent biotech scientists.

Over the past decade, Crews, the executive director of the Yale Molecular Discovery Center at West Campus, has been instrumental in helping spearhead two startups in the New Haven area. Most recently, Crews founded Arvinas, a company that aims to develop new drugs to treat cancer and autoimmune diseases. This past December, he was recognized as Entrepreneur of the Year by Connecticut United for Research Excellence, a state bioscience organization, which includes a range of science companies, universities, entrepreneurs and investors.

Crews, a resident of the greater New Haven area of 19 years, is a strong supporter of and believer in the local bioscience community and rejected an offer from a top-line Cambridge-based venture capitalist firm to purchase Arvinas.

“I wanted to keep the company here in New Haven, and the state made it very easy to say yes,” Crews said. “This is a home-grown biotech, and this is just one of the many advances in helping grow the local biotech community.”

Some young graduates are beginning to follow in Crews and Schlessinger’s footsteps. Sean Mackay SOM ’14 has decided to stay in New Haven next year to work on his business venture, IsoPlexis, which is selling a new technology to analyze cancer immune subsets. He cited mentorship through YEI and access to funding as “major drivers” in his decision to stay in New Haven next year.

Lynch said that in order to kick-start the startup culture, the city will need to create a few more of these poster boys like Crews and Schlessinger.

Feldman added that the culture of the city must reform until “failure is seen as success.” He explained that in large biotech hubs, even failures are seen as contributions to the industry because those involved in the company can bring their experience into a new venture.

“You just don’t see that in New Haven today,” Feldman said.

Developing the culture goes hand-in-hand with creating spaces that facilitate collaboration. While the Grove, a co-working space, and Bioscience Clubhouse Connecticut, a physical and virtual gathering space for state biotech entrepreneurs, provide important places to share information, there need to be more.

Connecticut Innovations’ Director of Bioscience Initiatives Margaret Cartiera said that infrastructure changes must take place to support mentorship, networking and other interactions that can keep and maintain companies in the area.

“We need a physical space where everyone can be slammed together,” Boyle said. “You need a place where all biotech companies can come and spend 16-18 hours together.”

He pointed to the Cambridge Innovations Center — a megaplex of over 600 companies where meeting rooms are set up to make work collaborative — as a location that has helped give rise to that city’s startup scene. MIT biology professor and Nobel Prize winner in physiology Phillip Sharp said this center has been particularly important in bringing new people out of the universities into entrepreneurial ventures. He added that globally renowned realty group Alexandria Real Estate Equities provides incubator space to small companies with space for up to 30-50 employees before they are ready to go out and receive a long-term lease.

“Those [companies] are all buildable by any person in any place, but it’s just twice or three times as fast and easy here,” Sharp said. “That creates momentum and makes [Cambridge] a very attractive place to be.”

Boyle said Yale and the city have a critical challenge of both making as many profitable biotechs as possible and keeping them in New Haven.

SILICON VALLEY, CAMBRIDGE AND NEW HAVEN?

Fostering a biotech culture is not only about making a city inviting for new entrepreneurs, but also about the ensuing support system that surrounds these scientists.

“We’ve created a virtuous cycle [in Cambridge] that’s hard to replicate,” said CEO of Cambridge-based biotech Ataxion Josh Resnick. “In biotech, it’s hard to build up that critical mass. New Haven certainly has the science and medicine, but the rest of the capital and entrepreneurship and executive talent is not quite there.”

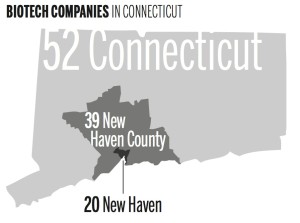

While San Francisco has $1.15 billion in biotech investing each year, with Boston/Cambridge coming up just behind at $933.59 million, New Haven has only ushered in $50 million per year. Director of the Yale Cancer Center Thomas Lynch ’82 MED ’86 said that New Haven is currently home to about 20-30 biotech companies, but the city would need to reach 50 or 60 to create a more self-sustaining environment for the industry. Sharp, who co-founded Biogen, one of the first major biotech companies in Cambridge, said that part of the secret to Cambridge’s success is that the city has a network of CEO’s and chief scientific leaders, patent lawyers, technicians, realtors and venture capitalists willing to invest in new projects.

If a city has these crucial support networks, new companies will be more likely to settle in the area.

“It is all very established territory, which allows a company or an investor to take uncertainty out of the process,” Sharp said. Taking away that uncertainty is critical in an industry like biotech, where expenses to transfer a product from pre-clinical phase to commercialization could cost up to $1.4 billion, according to Shannon.

Elm Street Ventures Founder and Managing Partner Rob Bettigole ’76 SOM ’83, whose company has invested in local startups, said New Haven’s comparatively later start to other biotech cities puts the Elm City at a disadvantage. Many argue that what the city needs is a more robust investing environment in Connecticut. Yale has venture firms in New Haven like Elm Street Ventures and Launch Capital, but there needs to be more.

“It’s not better science — in those places there is just a much larger number of existing companies,” Bettigole said. “Success breeds success, and then that attracts investors.”

Hasan Ansari SOM ’14 understands the competition for investors in New Haven. Ansari worked with a team through YEI to create TummyZen, a brand of antacid. He said he and his team struggled to raise money in the New Haven area to produce their pills and market the product online and in local pharmacies. Fortunately, using School of Management grants and YEI grants, Ansari and his team developed a website and created the first batch of their product last fall. He said that without the grant his team would have been out of luck.

Soderstrom believes that New Haven is not unique in the challenges it has faced in attracting investors. Only Cambridge and Silicon Valley, he said, do not suffer to the same extent from a similar lack of investors. Of all venture capital firms in the nation, Feldman predicted 65 percent of them are concentrated on one mile on Sand Hill Road in Menlo Park, a town near Palo Alto.

Nevertheless, Feldman does not think it’s really an issue of capital, as Yale and New Haven have access to capital through Southern Connecticut, a center of private equity, as well as access to New York City. The issue, rather, is building critical mass of companies so that scientists feel comfortable switching between quality jobs.

“They key to biotech is that these firms want to be near each other,” said Alpern. “That’s why you have hubs like Silicon Valley and Cambridge, because if a person is starting a business, they know that, if it doesn’t work out, they can switch to another company without moving. When a biotech company chooses to not set up in New Haven, it’s because of the location and proximity to other companies.”

Alpern said that New Haven has started to build this necessary critical mass by providing businesses spaces, zoning approvals and grant permits.

Feldman added Pittsburgh and Cleveland are logical places to have high-tech centers because they have great technical universities — Carnegie Mellon and Case Western — and a very low cost of living. But the culture there also isn’t quite right and as a result, the critical mass of biotech companies has not been built. As the industry continues to grow, many experts in the field believe that New Haven should not strive to reach the level of Cambridge or Silicon Valley — rather, New Haven must put itself in a more competitive position to ensure that those with innovative ideas in biotech stay in the Elm City.

“New Haven doesn’t have to replicate anything, but it can be a very exciting and interesting biotech area with virtues independent of those,” Shannon said. New Haven’s relatively low cost of living is one such advantage.

The BiotechFierce article that ranked New Haven the 13th best biotech city in the country ended with the following statement: “Connecticut may not be the first place that biotech entrepreneurs have in mind when they start a company, but when the circumstances are right it can make a lot of sense.”

Soderstrom thinks that people are beginning to notice, adding that, “I don’t think it’s coincidence that I got an email from a CEO last week that was thinking about setting up in Cambridge and thinks they should be thinking about New Haven instead.”