When Peter Salovey arrived at Yale as a graduate student in 1981, roughly one in five degrees from Yale College were awarded in science, math or engineering. Over the next three decades, Salovey became a world-renowned psychologist, dean of the Graduate School and of Yale College, provost, and finally president-elect of the University. But as he prepares to take the highest University office, STEM still claims just one in five Yale degrees.

In many important ways, the sciences at Yale have not kept pace with Salovey’s rise, and the president-elect inherits both the accomplishments and unrealized goals of outgoing President Richard Levin.

Four new science buildings stand on Science Hill as the result of half a billion dollars Levin pledged to the sciences more than a decade ago. After a concerted Yale effort to recruit more students interested in majoring in STEM, the class of 2016 marks the first time more than 40 percent of the incoming class intend to pursue degrees in those fields. In the last decade, multiple departments have revamped introductory courses to help retain the growing number of students intending to major in the sciences.

But questions remain about whether Yale will ever be able to shake its image as an institution that values the humanities over the sciences. The new biology building, promised to the Science Hill faculty more than a decade ago, remains a quarter-billion dollar fantasy.

In Salovey, molecular biologists and theoretical chemists may not be getting one of their own. But conversations with more than two dozen students, faculty and administrators suggest that the science community at Yale recognizes Salovey as an accomplished researcher and ally. While he has not released detailed plans for the sciences under his presidency, Salovey has signaled that he will prioritize faculty growth, modernizing facilities and fostering a science culture.

“I think he is very committed to making the sciences as strong as they can be,” psychology professor Frank Keil said. “I think he understands that is a very important part of Yale’s future, and he definitely wants to commit to it. I have no doubt about that.”

BUILDING ‘A GOOD TRAJECTORY’

In the 1980s, the physical infrastructure around the whole campus was in a state of disrepair, said Yale College Dean Mary Miller. The coat of paint applied to her office in the early 1990s was the first since World War II.

“Maybe you could limp along without a new coat of paint in basic classroom buildings on the central campus,” she said. “But in fact, cutting-edge science was hard to perform in outmoded or nonexistent facilities. Yale had to work very hard, starting in the Levin years, to reinvigorate the faculty, to address concerns about facilities, and to inspire a generation of undergraduates about the exciting opportunities in science, engineering, technology and math.”

In January 2000, Levin pledged $500 million for the science and engineering facilities to fund the construction of five new buildings and the renovation of existing ones. Many of the science buildings were the oldest at Yale, presenting challenges for conducting science, attracting faculty, and promoting a culture of science and engineering in the student body. A month later, Levin announced another $500 million for the then cash-strapped medical school over the next decade.

The first of the five buildings, the Class of 1954 Environmental Science Center, opened in early 2002. Malone Engineering Center opened three years later, as did the Class of 1954 Chemistry Research Building. Kroon Hall welcomed the School of Forestry & Environmental Studies in 2008.

The fifth building, and perhaps the initiative most central to the Science Hill growth plan, was the $250 million Yale Biology Building, said Deputy Provost for Science and Technology Steve Girvin. The 326,400-square-foot facility on Science Hill, which biology professor Sidney Altman said had been promised to the faculty since the late 1990s, would primarily serve as the home for the Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology Department — a department Girvin said was in “sore need” of new laboratory space.

But in 2007, Yale spent $109 million on the sciences — seven miles away from Science Hill. With the purchase of the 136-acre former Bayer Pharmaceuticals plant, the University added 1.6 million square feet of research facilities, office and storage space for Yale sciences and engineering as well as for Yale art and library collections. At the time, Levin said the laboratories already on the property would have cost between $300 and $400 million to build on their own.

One year after the West Campus purchase, the economic recession crushed the Yale endowment. Assets valued at $22.9 billion tumbled to $16.3 billion in the span of months. With it, the growth of faculty labs slowed to a trickle on West Campus and has only recently started to recover. Back on Science Hill, plans to break ground on the Yale Biology Building were shelved indefinitely. Today, a $100 million solicitation for the building sits on the “Giving to Yale” website.

The most significant challenge facing Yale Science is the state of the facilities, Salovey said. West Campus, he said, is key to Yale’s ability to solve interdisciplinary science problems. The facility is organized into six institutes — Chemical Biology, Cancer Biology, Nanobiology, Systems Biology, Microbial Diversity and Energy Sciences — that share four core facilities: a center for molecular discovery, a center for genome analysis, a high-performance computing center and an analytical chemistry facility. Salovey said continuing to support West Campus growth and faculty recruitment, currently at about 25 percent capacity, is one of his top priorities.

Restarting construction on the Yale Biology Building is another “high priority,” Salovey said, adding that it is very likely that the University would have to borrow money to finance the construction.

Altman called Yale’s long-standing unwillingness to borrow money to construct the Yale Biology Building a “repeated failure on the part of the administration.” This reality is not lost on many senior administrators, including Levin.

“I think we are on a good trajectory,” Levin said. “But my one big regret is that we were just ramping up to a tremendous amount of renovation on Science Hill — we did three buildings up there — but we had much more in the works, and the recession took the wind out of the sails.”

DIAGNOSING THE STEM PROBLEM

More than 40 percent of the class of 2016 expressed interest in majoring in STEM — the first group in Yale’s history planning to focus on these disciplines at such a high rate. During Altman’s last year as dean of Yale College in 1989, only 15 percent of the degrees were in STEM fields.

Exposure to science was not widespread among nonmajors, either. During Altman’s tenure as dean, 30 percent of Yale College students were graduating without having taken a single science course. Altman said he was dismayed by this lack of scientific education and worked to encourage undergraduate exposure to the sciences. Soon, Yale students were required to take at least three courses in each distributional area outside of their area of major study, he said, including a minimum of two in the natural sciences. His administration also placed science counselors in each of the residential colleges to serve as tutors for students.

In 2001, Levin convened a Committee on Yale College Education to consider the state of undergraduate education, and in particular to evaluate whether Yale students were graduating with the requisite skills for the 21st century. Salovey, then-chair of the Psychology Department, led the working group on biomedical education. The report, released 10 years ago this month, laid out the challenges facing the College and especially those in the STEM departments.

“[The] undergraduate culture does not foster a high degree of interest in and respect for scientific inquiry,” it concluded. “Students frequently abandon science, not just as a possible major but even as a continuing interest, as a result of a single bad experience early on.”

The report suggested numerous remedies for this dire diagnosis. Yale College should embark on “major curricular initiatives” in the sciences, including developing attractive introductory science courses for nonmajors, providing freshmen with opportunities for research and reviewing the laboratory sections attached to introductory courses.

It was also this report that initially suggested the current system of distributional requirements. In the previous scheme, any course taught by a science faculty member could qualify for inclusion in the sciences group, said history professor Daniel Kevles, who served on the physical sciences working group. He said he remembers that Salovey was eager to ensure the new science requirement had “some teeth” in practice and was very supportive of the recommendation that a committee of faculty vet the distributional category given to each course.

“Peter was the person who had to put the CYCE into effect back when he was first dean,” Miller said. “It is the lessons that come out of the first CYCE that really will underpin a lot of Peter’s vision of Yale College. STEM teaching was heavily emphasized as needing improvement.”

AS DEAN AND PROVOST, PROFESSOR SALOVEY

William Segraves spends a lot of time thinking about how to teach science. As associate dean for science education, Segraves has helped revamp many introductory science courses at Yale to reduce the number of students who leave the sciences for good after the “single bad experience” named in the CYCE report. Girvin said Salovey has been a strong supporter of improving early undergraduate education in STEM disciplines.

The Physics Department launched a new introductory course for the biomedical sciences, PHYS 170/171, about four years ago.

“Students are looking at that course and saying, ‘Now I understand what physics has to do with my interests,’ in a way that they didn’t before,” Segraves said. “I think that’s been a real success.”

A year later, in fall 2011, both the Math and Chemistry departments unveiled introductory courses with a greater focus on biological applications. The introductory biology sequence saw a revision last fall as well.

Segraves said the departments are still tweaking these young courses. In the first two modules of the revised introductory biology sequence, 35 percent of students rated the courses “below average” or “poor.” By comparison, only 22 percent of students gave these two lowest ratings to the semester-long course the modules replaced.

“There have been some areas where we have seen considerable improvements in terms of course offerings, other areas where we are still lagging behind,” Levin said. “I think there is still a lot of work to be done there to make sure that our introductory science courses are going to actually encourage interest in science instead of discouraging it.”

In addition to reimagining STEM instruction, the CYCE highlighted increasing research experience as an important component of improving the STEM experience at Yale.

The Yale College Dean’s Research Fellowship expanded “exponentially” over the last decade according to Segraves, adding that Salovey’s support as dean was critical to its growth. In 2001, the program supported only six students with summer research, but last summer 88 received between $3,440 and $4,300 each for eight to 10 weeks of summer work, much of which happened in the sciences.

“We are seeing what happens when you do the things we have been doing for the last five years,” Segraves said. “We have more students graduating with STEM majors, and they are having great experiences. It’s not a coincidence that Yale had a boatload of Rhodes scholars this year and that three or four of them were scientists.”

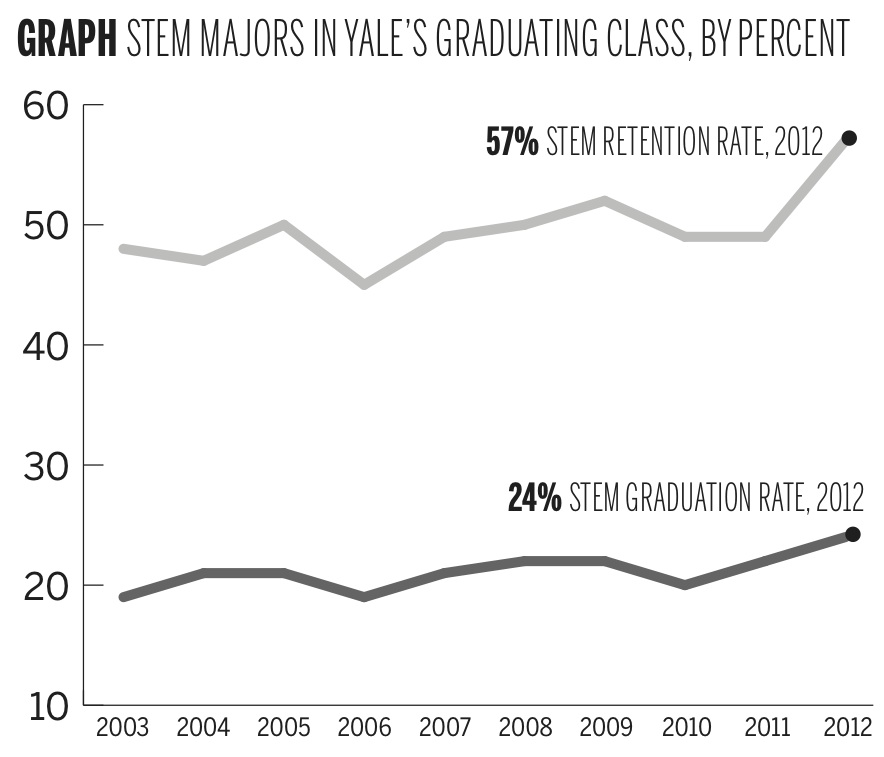

Over the last decade, roughly half of STEM students have stuck with the field until graduation, according to data from the Yale Office of Institutional Research. In the class of 2012, for example, 57 percent of students who initially indicated interest in STEM graduated with a degree in the field. But retention rates over the first and second half of the past decade are virtually identical, at 48 and 51 percent, respectively, and a 2011 report following up on the CYCE recommended that the College still do more to retain STEM students. Preventing students from leaving STEM fields remains a “concern” going into Salovey’s administration, Girvin said.

Levin pushed hard to attract an incoming class with 40 percent of students indicating interest in a STEM field, and Salovey said he has not yet decided how he wants to shape the student body.

“I’m mainly interested in finding the very best applicants that are out there and getting them to come to Yale,” he said. “We are more attractive in that way to those with a science and engineering interest than we used to be, and I think that’s a good thing.”

THE FACULTY KEY

Directly or indirectly, all of Salovey’s goals for the sciences aim to boost faculty recruitment.

Salovey said his primary objective is to elevate the reputation of Yale’s physical sciences and engineering departments to the level of the life sciences — the umbrella term for the biological sciences on Science Hill and biomedical research at the medical school — by hiring strong senior and promising junior faculty. Attracting faculty to engineering got a financial boost in 2011 with a $50 million gift to endow 10 new professorships, and Salovey said he will work with Engineering Dean Kyle Vanderlick to fill those positions. Attracting top faculty will become easier once Yale finishes rehabilitating the facilities on Science Hill, Salovey said, and creating a more “vibrant” STEM culture will help draw faculty as well.

In these goals, Salovey did not mention increasing the number of female faculty members in the sciences. At Yale College, approximately 11 percent of tenured faculty in the physical sciences are female, a rate which has roughly doubled since 2002 according to the Women Faculty Forum.

Jessica Tordoff ’15 said she thinks recruiting female faculty in the sciences should be a top priority for Salovey. As a computer science and molecular, cellular and developmental biology double major, she said her only course taught by a woman this year was her language class.

“That’s a really big deal, having female professors, because it’s something we are definitely missing,” she said. “Although it looks like we are making great bounds in there being more and more women STEM undergraduates every year and that’s really valuable and great, it’s really sad that you look at your professor and think, ‘I’ve had zero [female] STEM professors in 10 classes this year.’”

Though he did not explicitly mention faculty gender parity as a top priority, Salovey has shown commitment to diversity among faculty in his time as provost, said Deputy Provost for the Social Sciences and Faculty Development Frances Rosenbluth, citing his role in helping establish the University Faculty Diversity Committee in 2011.

In fact, while Salovey may not be a physicist or biologist, he was nearly an engineer. Faculty say Salovey’s broad exposure to fields beyond psychology allow him to empathize with professors throughout the University.

At the opening of the Center for Engineering Innovation and Design in February, Salovey said he nearly pursued engineering at Stanford as an undergraduate. In high school, he received the Cornell Society of Engineers award and the Rensselaer Medal, given to distinguished seniors in math and science, he said. His father, too, was a professor of chemical engineering and materials science.

Psychology professor Frank Keil said Salovey displayed a broad understanding of science beyond his home discipline of psychology. When Salovey chaired a recent senior appointments committee in the physical sciences, Keil said Salovey became “genuinely excited” about the research and displayed an impressive base of background knowledge.

“I think that he has credibility with the scientists on campus, and that helps immensely,” Keil said. “He is quantitatively sophisticated, and he understands how to run a lab and experimental methodology. He can speak the language.”

The scientific community views Salovey as a “friend of the sciences” because he can empathize with the process of securing and maintaining grant support, especially in challenging fiscal times like the present, said Vice President of West Campus Planning and Development Scott Strobel.

In a symposium for new faculty on West Campus last year, Salovey talked about his start at Yale as an assistant professor in the late 1980s and the process of establishing a research operation. Jesse Rinehart GRD ’04, an assistant professor of physiology who attended the talk, said he is optimistic about Salovey’s impact on the sciences because he understands the inner workings of being a successful researcher. Despite researching in a field distinct from Salovey’s, Rinehart said he thinks Salovey understands fully what it takes to compete for funding in the modern life sciences environment. Levin, too, said he thinks Salovey has a “natural affinity” with many of Yale’s scientists because of how well he understands the process for securing research grants.

For Robert Alpern, dean of the Yale School of Medicine, Salovey’s personal qualities are more important than his research accomplishments for his future in office.

“He is a great listener and a clear thinker, and that is what is so critical,” Alpern said. “It obviously helps that he has had grants from the NIH, and so he understands that world and that makes it easier for us, but I don’t think that means for us that he is necessarily going to favor science over art or humanities or anything like that. I think he is going to think it through and be a president for everyone.”

A PRESIDENT FOR EVERYONE

In the sciences alone, Salovey is being pulled in many directions. Salovey’s focus on faculty hiring on Science Hill and West Campus promises to be very costly. Modernization of teaching classrooms and labs on Science Hill continues, as the $250 million price tag on the Yale Biology Building looms.

Another issue that may take up an increasing amount of Salovey’s time is “bridge funding” — University support for researchers who are struggling to maintain continuing grant funding. The recent federal sequester exacerbated the already difficult process of securing grants from agencies like the National Institutes of Health, West Campus researcher Rinehart said. He said he hopes the Salovey administration responds in an “extremely generous and supportive fashion” and looks to innovative ways to continue the University’s ongoing robust research initiatives.

Salovey noted that while the STEM fields need the most care, the University must not neglect its other strengths.

“Yale has an outstanding reputation in the arts and humanities, and it’s very important that we not be complacent about that reputation,” he said. “And so as we continue to focus on science and engineering, we also need to recognize that we need to attend to the arts and humanities simultaneously.”

Along with modernizing teaching spaces and supporting initiatives at the CEID, Salovey said constructing the two new residential colleges near Science Hill — a $500 million project — will help foster a STEM culture at Yale by reducing the “psychological distance” to Science Hill.

Keil said he thinks one of Salovey’s strengths as president will be his ability to balance all the initiatives demanding University resources.

“He has remarkably strong backgrounds from so many different facets of Yale, so many connections across the whole community,” Keil said. “Not just in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, but in the medical school, the School of Management, and the Law School. He knows Yale and has experienced Yale and celebrated the scholarship of Yale across all the disciplines. Yes, I think he fully gets the sciences, but I think he also fully gets the social sciences and he fully gets the humanities. I think everyone is going to feel like he is in their corner, which is a hard thing to do.”